CONFEDERATE GENERAL JUBAL EARLY ABANDONS WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA

On August 11, 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early leaves Winchester, Virginia, as Union General Philip Sheridan nears the city. Wary of his new enemy, Early exited the area to avoid an immediate conflict.

(Image: General Jubal A. Early. The Virginia Historical Society)

Since June, Early and his 14,000 soldiers had been in the Shenandoah Valley area. He had been ordered there by General Robert E. Lee, whose Army of Northern Virginia was trapped near Richmond, Virginia, by the army of Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Early’s endeavor was meant to engage Grant, and he carried out his mission very well. In July, Early moved down the Shenandoah Valley to the Potomac River, defeating two Federal forces before arriving on the periphery of Washington, D.C. Grant ordered soldiers from his army to move Early from the Washington area, but Early simply returned to the Shenandoah and went on operating with impunity.

Now Grant sent General Philip Sheridan to handle Early and his force. Sheridan took command of the Army of the Shenandoah on August 1, and he took action as soon as he arrived on the scene. On August 10, he moved his army toward Winchester. Early was worried and left the city on August 11 to a more defensible position 20 miles south of Winchester. Sheridan and his army followed Early, positioning his soldiers along Cedar Creek—just north of Strasburg, Virginia.

As dictated by Grant, Sheridan stopped to await reinforcements. His army, consisting of both infantry and cavalry, would subsequently total 37,000 soldiers. Sheridan waited for a few days, but Confederate raider John Mosby and his Rangers burned a large cache of Sheridan’s supplies. Alarmed and almost out of food, Sheridan pulled back on August 16. This retreat was similar to many Union operations in Virginia during the war. Early and others thought Sheridan was as tentative and hesitant as other Union commanders. That opinion changed little during the next month as Sheridan continued to wait and gather his force.

However, Sheridan would soon show he was very distinct from previous Union leaders. In September, he began a campaign that drove the Confederates from the valley and then rendered the area useless to the Southern cause by destroying all the crops and supplies.

BABE RUTH HITS 500th Home Run

On August 11, 1929, New York Yankees slugger Babe Ruth becomes first MLB player to hit 500 home runs (off Willis Hudlin) in 6-5 loss to Indians at League Park, Cleveland.

(Image: Lou Gehrig, Tris Speaker, Ty Cobb, and Babe Ruth, 1928. Wikimedia Commons.)

George Herman “Babe” Ruth (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. Nicknamed “the Bambino” and “the Sultan of Swat“, he began his MLB career as a star left-handed pitcher for the Boston Red Sox, but achieved his greatest fame as a slugging outfielder for the New York Yankees. Ruth is regarded as one of the greatest sports heroes in American culture and is considered by many to be the greatest baseball player of all time. In 1936, Ruth was elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame as one of its “first five” inaugural members.

At age seven, Ruth was sent to St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, a reformatory where he was mentored by Brother Matthias Boutlier of the Xaverian Brothers, the school’s disciplinarian and a capable baseball player. In 1914, Ruth was signed to play Minor League baseball for the Baltimore Orioles but was soon sold to the Red Sox. By 1916, he had built a reputation as an outstanding pitcher who sometimes hit long home runs, a feat unusual for any player in the dead-ball era. Although Ruth twice won 23 games in a season as a pitcher and was a member of three World Series championship teams with the Red Sox, he wanted to play every day and was allowed to convert to an outfielder. With regular playing time, he broke the MLB single-season home run leader in 1919 with 29.

After that season, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold Ruth to the Yankees amid controversy. The trade fueled Boston’s subsequent 86-year championship drought and popularized the “Curse of the Bambino” superstition. In his 15 years with the Yankees, Ruth helped the team win seven American League pennant and four World Series championships. His big swing led to escalating home run totals that not only drew fans to the ballpark and boosted the sport’s popularity but also helped usher in baseball’s live-ball era, which evolved from a low-scoring game of strategy to a sport where the home run was a major factor. As part of the Yankees’ vaunted “Murderers Row” lineup of 1927, Ruth hit 60 home runs, which extended his own MLB single-season record by a single home run. Ruth’s last season with the Yankees was 1934; he retired from the game the following year, after a short stint with the Boston Braves. In his career, he led the American League in home runs twelve times.

During Ruth’s career, he was the target of intense press and public attention for his baseball exploits and off-field penchants for drinking and womanizing. After his retirement as a player, he was denied the opportunity to manage a major league club, most likely because of poor behavior during parts of his playing career. In his final years, Ruth made many public appearances, especially in support of American efforts in World War II. In 1946, he became ill with nasopharyngeal cancer and died from the disease two years later. Ruth remains a major figure in American culture.

WATTS REBELLION BEGINS

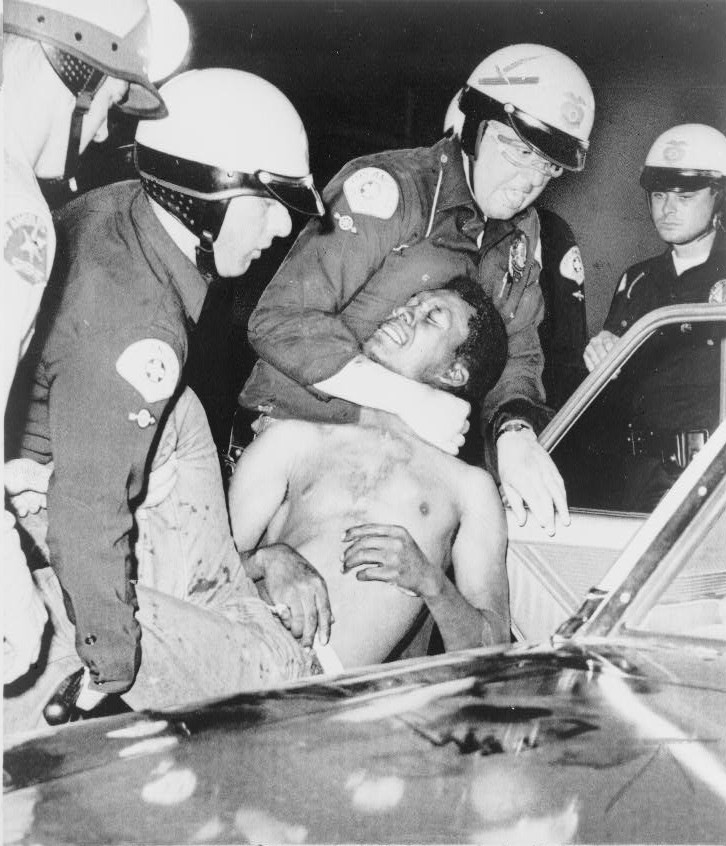

On August 11, 1965, in the Black neighborhood of Watts, in Los Angeles, racial tension reached a boiling point after two white policemen fought with a Black motorist suspected of drunken driving. A crowd gathered near the corner of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street to observe the arrest. They soon became angry by what they felt was yet another case of racially motivated abuse by the police.

(Image: Police arrest a man during the riots on August 12, 1965. Wikimedia Commons.)

An insurrection soon began, prompted by residents of Watts who were alienated after years of economic and political segregation. The rioters eventually covered a 50-square-mile area of South-Central Los Angeles, looting stores and burning buildings as snipers shot at police and firefighters. Finally, with the assistance of thousands of National Guardsmen, the violence ended on August 16.

The five days of violence left 34 dead, 1,032 injured, nearly 4,000 arrested, and $40 million worth of property destroyed. The Watts Rebellion, also known as the Watts Riots or the Watts Uprising, presaged many rebellions to occur in the ensuing years, including the 1967 Detroit Riots and Newark Riots.

Leave a comment