KING PHILIP’S WAR ENDS

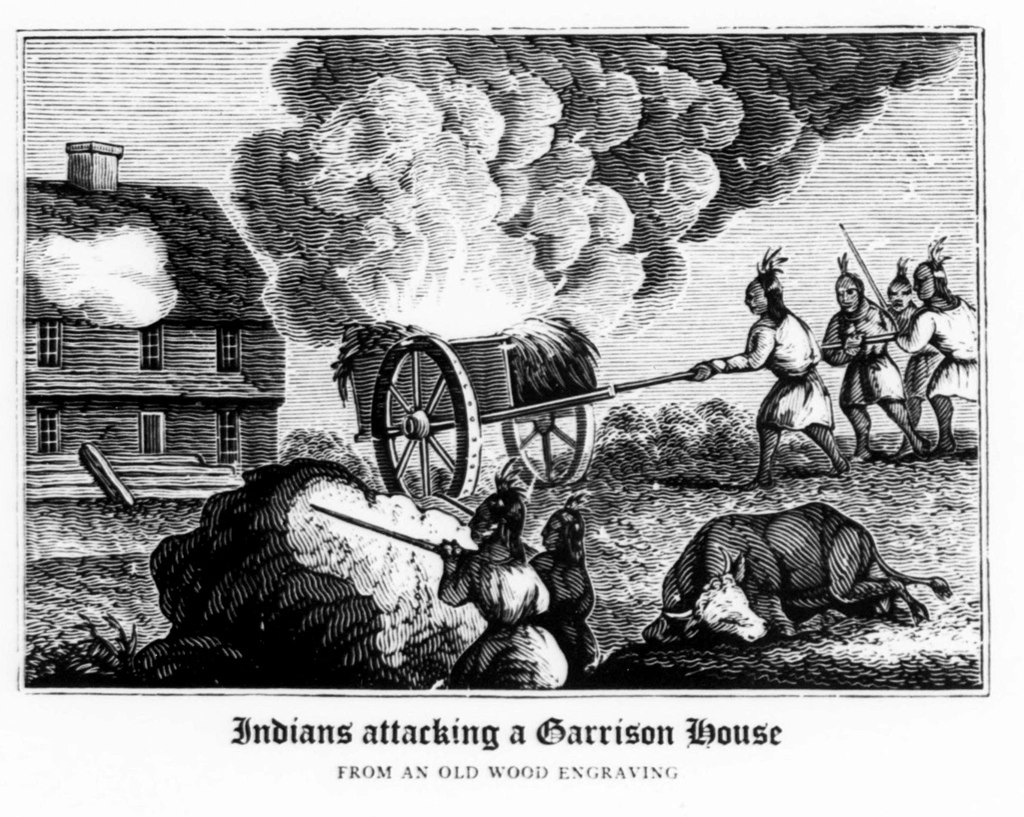

Image: Indians Attacking a Garrison House, from an Old Wood Engraving This is likely a depiction of the attack on the Haynes Garrison, Sudbury, April 21, 1676. (Wikimedia Commons.)

On August 12, 1676, in colonial New England, King Philip’s War ended when Philip, chief of the Wampanoag tribe, was assassinated by a Native American warrior in the employ of the English.

In the early 1670s, over 50 years of peace between the Plymouth colony and the Wampanoag Indians began deteriorating when the swiftly growing settlements-imposed land sales on the tribe. Reacting to increasing Native American hostility, the English met with King Philip, chief of the Wampanoag, and insisted that his forces surrender their weapons. The Wampanoag did that, but in 1675 a Christian Native American who had been working as an informer to the English was murdered, and three Wampanoag warriors were tried and executed for the offense.

On June 24, King Philip reacted by commanding a raid on the settlement of Swansea, Massachusetts. His warriors murdered the English colonists there, and the raid set off a series of Wampanoag attacks where several settlements were destroyed and many colonists were killed. The colonists retaliated by destroying several tribal villages. The English’s destruction of a Narragansett village brought the Narragansett tribe into the conflict as an ally of King Philip. Within a few months, a number of other tribes and the entirety of New England colonies were involved in the war.

In early 1676, the Narragansett were defeated and their chief killed, while the Wampanoag and their other allies were eventually overwhelmed. King Philip’s wife and son were captured, and his secret headquarters in Mount Hope, Rhode Island, were discovered. On August 12, 1676, Philip was assassinated at Mount Hope by a Native American working for the English. The English drew and quartered Philip’s body and publicly displayed his head on a pike in Plymouth.

King Philip’s War, which was tremendously costly to the colonists of New England, ended Native American dominance in the region and brought in a period of unrestricted colonial expansion.

Self-Proclaimed Emperor Joshua Abraham Norton of the USA Issues Edict Abolishing the Democratic and Republican Parties

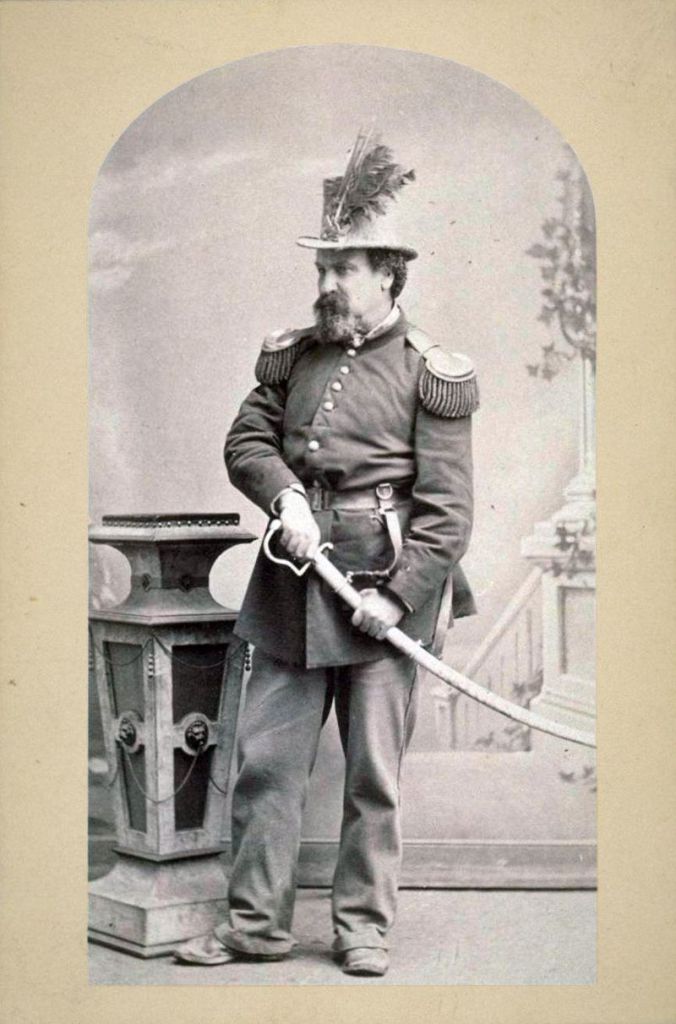

Image: Emperor Norton in full dress uniform and military regalia, his hand on the hilt of a ceremonial sabre, c. 1875. (Wikimedia Commons)

On August 12, 1869 self-proclaimed Emperor Joshua Abraham Norton of the USA issues edict abolishing the Democratic and Republican parties.

Joshua Abraham Norton, known as Emperor Norton, was a resident of San Francisco, California, who in 1859 proclaimed himself “Norton I., Emperor of the United States”. In 1863, after Napoleon III invaded Mexico, he took the secondary title of “Protector of Mexico”.

Norton was born in 1818 in England but lived his early life in South Africa. Leaving Cape Town, in 1845, he arrived in Boston, via Liverpool, in March 1846 and San Francisco in late 1849. For the first few years after arriving in San Francisco, Norton made a successful living as a commodities trader and real estate speculator. However, he was financially ruined following a failed bid to corner the rice market during a shortage prompted by a famine in China. He bought a shipload of Peruvian rice at 12 cents per pound (26 ¢/kg); but more Peruvian ships arrived in port, causing the price to drop sharply to three cents per pound (6.6 ¢/kg). He then lost a protracted lawsuit in which he tried to void his rice contract, and his local prominence faded.

Norton did not disappear from the scene completely. However, he dramatically “reset” his relationship to the world around him in September 1859, when he proclaimed himself “Emperor of the United States”. Norton had no formal political power; nevertheless, he was treated deferentially in San Francisco, and currency issued in his name was honored in some establishments that he frequented. Some considered Norton to be insane or eccentric, but residents of San Francisco and the city’s larger Northern California orbit enjoyed his imperial presence and took note of his frequent newspaper proclamations. Though Norton received free ferry and train passage and a variety of favors, such as help with rent and free meals, from well-placed friends and sympathizers, the city’s merchants also capitalized on his notoriety by selling souvenirs bearing his image.

On January 8, 1880, Norton collapsed at the corner of California and Dupont streets and died before he could be given medical attention. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, nearly 10,000 people lined the streets of San Francisco to pay him respects at his funeral.

“Wings”, One of Only Two Silent Films to Win an Oscar for Best Picture, Opens in Theatres

Image: Clara Bow (Wikimedia Commons)

On August 12, 1927 “Wings”, one of only two silent films – the other being The Artist in 2011 – to win an Oscar for best picture, opens starring Clara Bow (Outstanding Picture 1929)

Clara Bow was an American actress who rose to stardom during the silent film era of the 1920s and successfully made the transition to “talkies” in 1929. Her appearance as a plucky shopgirl in the film It brought her global fame and the nickname “The It Girl”. Bow came to personify the Roaring Twenties[2] and is described as its leading sex symbol.

Bow appeared in 46 silent films and 11 talkies, including hits such as Mantrap (1926), It (1927), and Wings (1927). She was named first box-office draw in 1928 and 1929 and second box-office draw in 1927 and 1930. Her presence in a motion picture was said to have ensured investors, by odds of almost two-to-one, a “safe return”. At the apex of her stardom, she received more than 45,000 fan letters in a single month (January 1929).

Two years after marrying actor Rex Bell in 1931, Bow retired from acting and became a rancher in Nevada. Her final film, Hoop-La, was released in 1933. In September 1965, Bow died of a heart attack at the age of 60.

Leave a comment