On this day in history, at night, some 250 rounds of ammunition were fired into several buildings in Brownsville, Texas. One man was killed, and two others were wounded. The townspeople’s suspicions immediately fell upon the members of the 25th Infantry, an African American regiment. The soldiers had arrived in Brownsville sixteen days before the shooting and were stationed at Fort Brown, just outside of town and near the site of the incident. Tensions between the black troops and some openly racist Brownsville residents flared up. Although the soldiers and their white commander consistently denied any knowledge of the “raid,” as it came to be called, subsequent investigations sustained the townspeople’s opinion of their guilt.

History Daily: 365 Fascinating Happenings Volume 1 & Volume 2 – August 13, 1906

The Brownsville Affair occurred against a backdrop of deteriorating Black status: Texas, in that same year, extended railroad segregation to streetcars, did away with the black militia, and held the second all-white Democratic primary. The state saw over one hundred lynchings in the first decade of the century, the third highest in the United States. Furthermore, hostility towards African Americans in the area had been escalating. Since arriving at Fort Brown on July 28, 1906, the Black 25th Infantry soldiers had been forced to follow the legal color line mandate (which refers to the racial segregation that existed in America after the abolition of slavery) from white citizens of Brownsville, which included the state’s racial segregation law calling for separate accommodation for Black people and white people, and the Jim Crow customs of showing respect for white people, as well as observance of local laws.

An alleged attack on a white woman during the night of August 12 angered so many townspeople that Major Charles Penrose, the officer in charge of the 25th Infantry, after consultation with Mayor Frederick Combe, declared an early curfew for soldiers the next night to avoid any possibility of trouble.

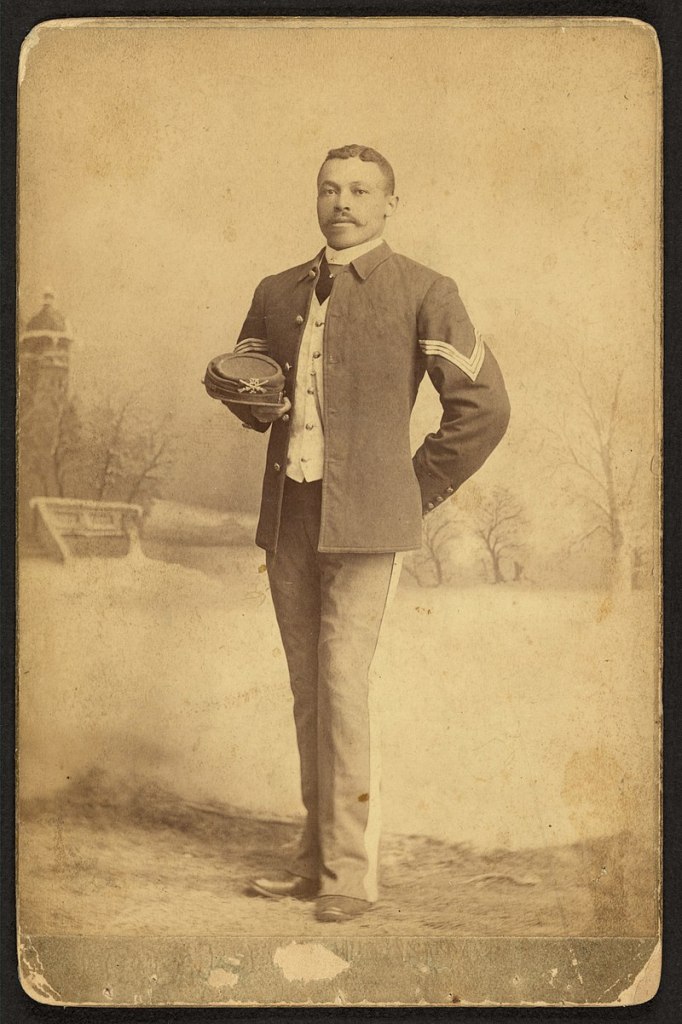

Image: Soldier of the 25th Infantry. (Wikimedia Commons)

On the evening of August 13, 1906, bartender Frank Natus was murdered, and a deluge of gunshots in the town injured a police Lieutenant plus one civilian. Immediately the town’s residents decided that the blame squarely lies with the Black soldiers of the 25th Infantry at Fort Brown. But the all-white commanders at Fort Brown confirmed that all the soldiers were in their barracks at the time of the shootings. Local whites, including Brownsville’s mayor, still claimed that some black soldiers participated in the shooting.

Local townspeople began providing evidence that the Black soldiers were the culprits in the shootings by producing spent bullet casings from Army rifles which they said belonged to the soldiers of the 25th Infantry. Although the contradictory evidence showed that the spent shells were planted to frame the men of the 25th in the shootings, investigators accepted the declarations of the local whites and the Brownsville Mayor as being true.

Despite the pressure to name the culprits, the men of the 25th stated that they had no idea who did the shooting. Captain Bill McDonald of the Texas Rangers investigated 12 enlisted men and attempted to tie the case to them. The local county court did not return any indictments based on these investigations, yet the residents kept up the pressure to have something done about the affair.

President Theodore Roosevelt, at the recommendation of the Army’s Inspector General, ordered that 167 of the Black soldiers of the 25th Infantry be dishonorably discharged because of their “conspiracy of silence.” Even though some accounts maintained that six affected soldiers were Medal of Honor recipients, they were not. Fourteen of these men were subsequently reinstated into the army. The dishonorable discharge stopped the 153 other men from ever working in a civil service or military capacity for the rest of their lives. Some soldiers had been in the service for over 20 years, while others were extremely close to retirement with pensions, which they lost.

The prominent African American educator and activist Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute, got involved with the case. He implored President Roosevelt to change his decision on the matter. Roosevelt disregarded Washington’s plea and allowed his determination to stand.

Major Penrose was court-martialled for “neglect of duty, to the prejudice of good order and military discipline”; McDonald accused him of trying to protect his soldiers from being prosecuted. During the trial, which ran from February 4 to March 23, 1907, Penrose called McDonald a “contemptible coward.” Penrose was acquitted of the allegation.

Blacks and many whites across the United States were outraged at Roosevelt’s moves. The Black community began to turn against him, even though it had previously supported the Republican president. The administration withheld news of the dishonorable discharges of the troops until after the 1906 Congressional elections were held so that the pro-Republican Black vote would remain in place. The case was a political football, with William Howard Taft, positioning for the next presidential candidacy, trying to avoid any trouble.

Leaders of many major Black organizations, such as the Constitution League, the Niagara Movement, and the National Association of Colored Women, tried to convince the administration not to discharge the soldiers but were unsuccessful. Senator Joseph Foraker of Ohio had lobbied for the investigation that had supported the innocence of the soldiers, and he filed a report supporting the integrity of the soldiers. In September 1908, prominent educator and leader W.E.B. DuBois recommended that Black people register to vote and remember how they were treated by the Republican administration when it came time to vote for president. DuBois instead endorsed Woodrow Wilson and his New Freedom platform. DuBois retracted the endorsement after the Wilson Administration’s segregation of the federal bureaucracy and Wilson’s private screening celebration for The Birth of a Nation.

In 1970, historian John Weaver investigated the Brownsville Affair, and he argued that the members of the 25th Infantry were innocent and deprived of their due process as guaranteed by the United States Constitution. After reading Weaver’s book about this matter, Congressman Augustus Hawkins of Los Angeles introduced a bill to have the Defense Department re-investigate the case to provide justice to the accused soldiers.

In 1972, the Army found the accused members of the 25th Infantry to be innocent. It recommended that President Richard Nixon pardon the men and award them honorable discharges without back pay. One surviving member of the 25th was given a tax-free pension of $25,000. He was honored in ceremonies in Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles.

ON SALE NOW!!!

History Daily: 365 Fascinating Happenings Volume 1

In the United States:

In Canada:

Leave a comment