CHINA DECLARES WAR ON GERMANY

Image: Chinese workers during World War I (Wikimedia Commons)

On August 14, 1917, as World War I entered its fourth year, China abandoned its neutrality and declared war on Germany.

From its beginning, the Great War was not restricted to the European continent; in the Far East, two competing countries, Japan and China, sought to find their place in the conflict. Japan, an ally of Britain since 1902, entered the war on August 23, 1914, and began to plan the capture of Tsingtao, the most significant German overseas naval base located on the Shantung Peninsula in China, by amphibious assault. Over 60,000 Japanese soldiers, assisted by two British battalions, subsequently violated Chinese neutrality about Tsingtao, capturing the naval base on November 7 when the German forces surrendered. That January, Japan presented China with the “21 Demands,” which included the direct Japanese control over Shantung, southern Manchuria, and eastern Inner Mongolia and the seizure of additional territory, including islands in the South Pacific controlled by Germany.

When China declared war on Germany on August 14, 1917, it aimed to earn itself a place at the post-war bargaining table. Above all, China sought to recapture control over the vital Shantung Peninsula and restate its strength before Japan, its most significant adversary and rival. At the Versailles Peace Conference after the armistice, Japan and China tried valiantly to convince the Allied Supreme Council—dominated by the United States, Britain, and France—of their respective claims on the Shantung Peninsula. A bargain was finally struck in favor of Japan, who backed away from their demand for a racial-equality clause in the treaty in exchange for control over Germany’s vast economic holdings in Shantung, including mines, railways, and the port at Tsingtao.

Though Japan promised to return Shantung to China eventually—it would do so in February 1922—the Chinese were deeply angry by the Allied decision to favor Japan at Versailles. A massive rally occurred in Tiananmen Square on May 4, 1919, railing against the peace treaty, which the Chinese delegation in Versailles refused to sign. A year after the peace conference ended, radical Chinese nationalists created the Chinese Communist Party, which, under the leadership of Mao Tse-tung and several other leaders of the anti-Versailles Treaty rallies, would go on to win power in China in 1949.

BATTLE OF BOTHNAGOWAN

Image: Macbeth, King of Scotland (Wikimedia Commons)

On August 14, 1040, King Duncan I of Scotland was killed in battle against his first cousin and rival Macbeth (not murdered in his sleep as in Shakespeare’s play). The latter does succeed him as King.

After Duncan’s death, Macbeth became king of Scotland, and in 1045 he defeated and killed Duncan’s father, Crínán, the abbot of Dunkeld. Duncan’s sons, Malcolm Canmore, and Donald Ban, both escaped, with Malcolm finding seeking refuge in England.

In 1054 Siward, Earl of Northumbria, led an army into Scotland to support Malcolm and defeated Macbeth at the Battle of Dunsinane. Malcolm would defeat and kill Macbeth at the Battle of Lumphanan in 1057, taking the crown after killing Macbeth’s stepson Lulach 18 weeks later.

Upon Malcolm’s death at the Battle of Alnwick in 1093, Donald was made King of Scotland. Donald exiled Malcolm’s sons, one of whom, Duncan II would briefly dethrone Donald in 1094 before another, Edgar, seized the throne in 1097 with the aid of William II of England.

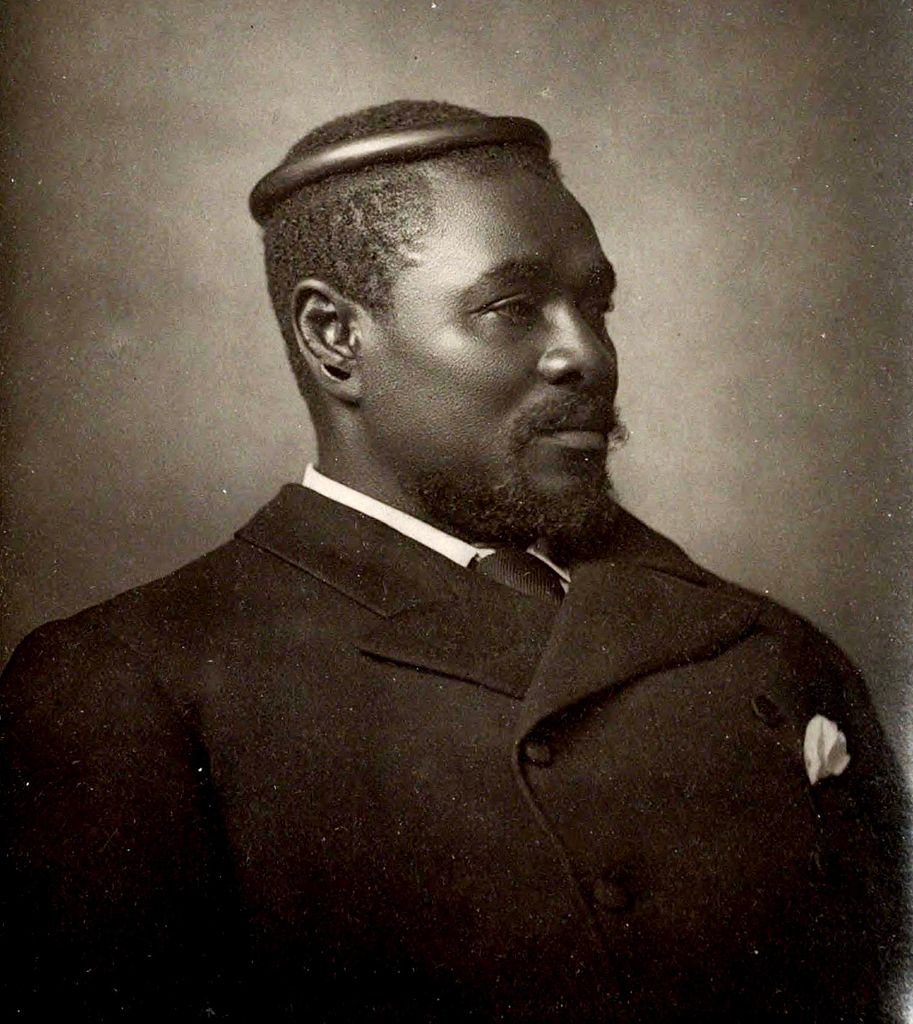

Queen Victoria Meets Zulu King Cetshwayo

On 14 August 1882 the Zulu King Cetshwayo met Queen Victoria on the Isle of Wight. The visit was the culmination of a diplomatic trip to England by Cetshwayo, intended to end his exile from Zululand, imposed after Britain’s defeat of Zulu forces in 1879. The visit changed not only popular opinion in Britain about Cetshwayo, but also Queen Victoria’s perception of the Zulu king.

Born around 1832, Cetshwayo succeeded his father Mpande as King of the Zulus in 1873. He was a talented diplomat but was regarded with suspicion by the British. In January 1879, a huge British force entered Zululand. Britain suffered its worst ever defeat at the hands of an indigenous opponent without modern weapons when the British camp at Isandlwana was captured by 24,000 Zulu warriors. Nevertheless, the Zulus were defeated on 4 July, and Cetshwayo was exiled.

Aided by a change in government in Britain in 1880, Cetshwayo managed to gain an audience with the queen and her ministers. On 4 August 1882, Cetshwayo arrived in England. Crowds gathered outside to see the 6ft 6in king, whom they had seen images of in the Illustrated London News.

King Cetshwayo had a brief meeting with Queen Victoria on 14 August 1882. The queen’s advisers cautioned her against too cordial an encounter with the man whose warriors had inflicted the defeat at Isandlwana. However, Victoria was quite impressed with Cetshwayo, describing him in her journal as, ‘A very fine man… I recognised him as a great warrior, who had fought against us, but rejoiced that we were now friends.’ She concluded the meeting by remarking that she respected him as a ‘brave enemy’. Victoria presented Cetshwayo with a silver ‘loving cup’ and commissioned her personal portrait painter, Carl Sohn, to make a portrait of the king. Cetshwayo later sent Victoria a basket and lid made from South African Zulu grass.

Following the audience with Victoria, Cetshwayo was informed that the British government now supported his reinstatement to the Zulu throne. In January 1883, Cetshwayo returned to Africa but the terms of his reinstatement contributed to a volatile political climate, and civil war broke out shortly after Cetshwayo’s return. Cetshwayo fled to British-controlled territory, where he died at Eshowe in February 1884.

Subscribe to History Daily with Francis Chappell Black for daily updates:

Leave a comment