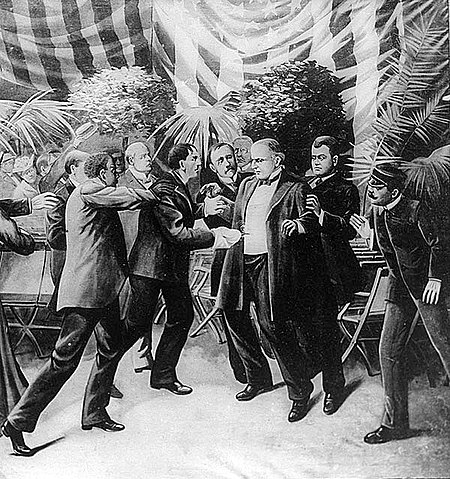

Image: Leon Czolgosz shoots President McKinley with a revolver concealed under a cloth rag. (Wikimedia Commons.)

On this day in history, President William McKinley is shaking hands and greeting visitors at the Pan-American Exhibition in Buffalo, New York, when a 28-year-old anarchist named Leon Czolgosz walks up to him and fires two shots into his chest. The president collapsed forward, saying, “Be careful how you tell my wife.”

At Buffalo’s Pan-American Exhibition, few attractions generated as much excitement as the two-day visit of President William McKinley. The 58-year-old was fresh off of guiding the United States to victory in the Spanish-American War, and he had entered his second term of office as one of the most popular Chief Executives in decades. On September 5, a record crowd of 116,000 filed into the World’s Fair to watch McKinley give a speech. That same evening, the Expo put on a patriotic fireworks display culminating with pyrotechnics that spelled out, “Welcome President McKinley, Chief of our Nation and Our Empire.”

McKinley’s final scheduled appearance at the Expo began the following day, September 6, when he attended a public meet-and-greet at a theater called the Temple of Music. Despite the withering late-summer heat, many people lingered outside the Temple of Music when the function began at 4 p.m. Near the beginning of the line stood 28-year-old Leon Czolgosz, a shy and morose former steelworker. A committed anarchist, Czolgosz, had arrived in Buffalo a few days before and purchased a .32 caliber Iver Johnson revolver. He now waited with the gun wrapped in a white handkerchief and hidden inside his coat pocket. “It was in my heart; there was no escape for me,” Czolgosz would later state. “All those people seemed to bow to the great ruler. I made up my mind to kill that ruler.”

The president’s nervous staff had added police and soldiers to his usual complement of Secret Service agents. Still, the security detail took little notice of Czolgosz as he moved closer to the president at around 4:07 p.m. When McKinley smiled and put out his hand, Czolgosz lifted his pistol—still wrapped in its white handkerchief—and fired two shots at point-blank range.

“There was an instant of almost complete silence, like the hush that follows a clap of thunder,” the New York Times later wrote. “The president stood stock still, a look of hesitancy, almost of bewilderment, on his face. Then he retreated a step while a pallor began to steal over his features. The multitude seemed only partially aware that something serious had happened.”

The stillness was only broken when James “Big Jim” Parker, a tall African American man waiting in line, punched Czolgosz and prevented him from firing a third shot. Several soldiers and detectives pounced on the assassin and beat him to a pulp. It took an order from McKinley before they finally stopped and dragged Czolgosz from the room. By then, blood was pouring from the president’s stomach and darkening his white formal vest. “My wife,” he managed to say to Cortelyou. “Be careful how you tell her—oh, be careful!”

Just a few minutes after the shooting, McKinley was taken to the Pan-American Exposition’s hospital from the Temple of Music. The only qualified doctor that could be found was a gynecologist, but the president was nevertheless rushed into the operating theater for emergency surgery. One of the bullets appeared to have ricocheted off one of McKinley’s suit buttons and hit his sternum, causing only minor damage. The other had struck his abdomen and passed clean through his stomach. The surgeon managed to suture the stomach wounds and stop the bleeding but could not locate the bullet, which he assumed was lodged somewhere in the president’s back.

Even with the .32 caliber slug still inside him, McKinley seemed to be on the mend in the days after the shooting. Doctors gave enthusiastic updates on his condition as he convalesced, and newspapers reported that he was awake, alert, and even reading the newspaper. Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was so pleased with McKinley’s progress that he took off on a camping trip in the Adirondack Mountains. By September 13, however, McKinley’s condition had become increasingly desperate. Gangrene had formed on the walls of the president’s stomach and brought on a severe case of blood poisoning. In a matter of hours, he grew weak and began losing consciousness. On September 14, at 2:15 a.m., he died with his wife Ida by his side.

By the time of McKinley’s death, Leon Czolgosz had already spent several days in a Buffalo jail cell undergoing interrogation by police. The Michigan native said he had pulled the trigger out of a desire to contribute to the anarchist cause. “I don’t believe in the Republican form of government, and I don’t believe we should have any rulers,” he said in his confession.

Czolgosz was only nominally connected to the American anarchist movement—certain groups had even suspected him of being a police spy—but his confession led to a sweeping roundup of political radicals. A dozen staff members from the anarchist newspaper “Free Society” were arrested in Chicago. On September 10, police also picked up the anarchist firebrand Emma Goldman, whose speeches Czolgosz had cited as a critical influence in his decision to assassinate McKinley. Goldman and the others were all eventually released, but justice came swiftly for Czolgosz. His murder trial began on September 23—a little more than a week after McKinley’s demise—and he was found guilty and sentenced to death just three days later. On October 29, 1901, Czolgosz was executed by the electric chair at New York’s Auburn Prison.

While William McKinley was eventually overshadowed by his more famous successor, Theodore Roosevelt, his assassination prompted a worldwide outpouring of grief. In Europe, the British King Edward VII and other monarchs declared national periods of mourning for the fallen president. A sea of sympathizers later came to view McKinley’s body as it lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda on September 17, and whole cities ground to a halt to pay their respects as his funeral train passed by on its way to his final resting place in Canton, Ohio. In 1907, the president’s remains were moved to a sprawling tomb complex featuring a domed mausoleum. The memorial includes a bronze statue that depicts McKinley giving his final speech at the Pan-American Exposition on September 5, 1901—the day before his fateful meeting with Leon Czolgosz.

Subscribe to History Daily with Francis Chappell Black to receive daily updates on new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

ON SALE NOW!!!

History Daily: 365 Fascinating Happenings Volume 1 – VOLUME 2 NOW AVAILABLE

In the United States:

In Canada:

Leave a comment