Today we begin a new series, appearing every Wednesday, profiling one notorious outlaw who was roaming the American Wild West in the late-1800s. I hope that you will enjoy the series as much as I did writing it. Enjoy!.

Francis

John Wesley Hardin

John Wesley Hardin was an Old West outlaw and gunfighter. Hardin was often in trouble with the law, even from an early age. He killed his first man at the age of 15, claiming it was done in self-defense.

Chased by lawmen for the more significant part of his life, in 1877, when he was only 23, he was sentenced to 25 years in prison for murder. Hardin maintained that he had killed 44 men at the time of sentencing, while historians attribute 27 deaths to him. While in prison, Hardin wrote an autobiography and studied law. He was known for exaggerating or fabricating stories about his life and claimed credit for numerous killings that cannot be documented.

Within a year of his release from prison in 1894, Hardin was murdered by John Selman Sr. in an El Paso saloon.

(Photo: John Wesley Hardin. Wikimedia Commons.)

John Hardin was born in 1853 near Bonham, Texas, to James Gibson “Gip” Hardi, a Methodist preacher, and Mary Dixson. He was named after John Wesley, the creator of the Methodist church.

Hardin described his mother, in his autobiography, as “blond, highly cultured… [with] charity predominated in her disposition.” Hardin’s father traveled all over central Texas preaching until he decided to settle his family in Sumpter, Trinity County, Texas, in 1859. Hardin’s father established and taught there at the school that John Hardin and his siblings attended.

In 1862, at age nine, Hardin attempted to run away from home and join the Confederate Army.

In 1867, while attending his father’s school, Hardin was teased by another student, Charles Sloter. Sloter blamed Hardin for creating graffiti on the schoolhouse wall that offended a girl in his class. Hardin denied writing the poetry, claiming that it had been Sloter who was the author. Sloter ran at Hardin with a knife, but Hardin stabbed him with his own knife, nearly killing him. Hardin was almost expelled from school over the confrontation.

Hardin had a propensity for violent rage from a young age. At 15, in 1868, Hardin shot a Black man named “Maje” to death after a wrestling match turned heated. According to Hardin, Maje called him a coward and started chasing him, waving a stick. Hardin then shot Maje and fled the scene looking for help. When he returned, Maje was dead and, afraid that the Union soldiers would not give him a fair trial, decided to run. By the time Hardin was finally sentenced to prison in 1878, he had maintained that he had killed 44 men. That may have been an exaggeration, though historians have only been able to confirm 27 of those deaths.

In 1871, when Hardin was only 18 years of age, a Texas rancher hired the young gunman as a trail boss for cattle drives up the Chisholm trail to Abilene, Kansas. Hardin was eager to exit Texas because a few days before, he had killed a Texas state policeman who was transferring him to Waco for a trial. Hardin needed to lay low and out of law enforcement’s gaze, but, as usual, he could not keep his temper in check. During the cattle drive, a Mexican herd had drew close to Hardin’s cows from behind. Hardin spoke to the Mexican in charge of the other herd about the situation, and when the exchange grew heated, Hardin shot the man in the head. A firefight opened between the two camps, and, according to Hardin, six vaqueros were shot and killed (five of those by Hardin). On the same cattle drive, Hardin claims to have killed two Indians in separate instances.

When Hardin and his herd arrived in Abilene, Kansas, on June 1, 1871, the town marshal, Wild Bill Hickok, was unconcerned with prosecuting murders that had taken place outside of his jurisdiction. On the contrary, he took an almost paternalistic interest in the young gunslinger – Hardin was 16 years his junior – and the two men began an uneasy friendship. Like many early Western lawmen, Wild Bill Hickok had created a tremendous reputation by committing several killings. Hickok may have believed he was a hot-tempered young man who would eventually become a reasonably valuable and law-abiding citizen. For his part, Hardin was very proud to be associated with the celebrated gunfighter.

On his first night in Abilene, Hardin was approached by Hickok, who declared to him that he was wearing guns in violation of town ordinance and ordered him to surrender his weapons, which he did but in a surprising way: Hardin handed the guns to Wild Bill butts forward, then quickly rolled them over and all of a sudden Wild Bill was staring right into their muzzles. However, both men eventually did back down. Hickok did not know that Hardin was a wanted man and told Hardin to avoid problems while in Abilene.

Hardin met up with Hickok again on a cattle drive in August 1871. This time, Hickok allowed Hardin to keep his pistols and bring them into town – something he had never allowed others to do. For his part, Hardin was captivated by Wild Bill and rejoiced in being seen on personal terms with the famous gunfighter. Hardin contended that when his cousin, Mannen Clements, was incarcerated for the slaying of two cowhands in July 1871, Hickok – at Hardin’s request – arranged for his getaway.

Not long afterward, on August 6, 1871, Hardin’s cousin Gip Clements and a friend named Charles Couger rented rooms at the American House Hotel after an evening of revelry and gambling. Clements and Hardin shared one room while Couger was in another. All three had been drinking heavily all evening long. Sometime during the night, Hardin was awakened by loud snoring from Couger’s room. He yelled at the man several times to “roll over” and then, angry by the lack of response, drunkenly fired numerous bullets through the shared wall to awaken the sleeping man. Couger was hit in the chest by one of the stray bullets as he lay in bed and was killed immediately. Although Hardin did not mean to kill the man, he had violated an ordinance prohibiting gun firing within city limits. Half-dressed and still drunk, he and Clements escaped through a second-story window onto the hotel’s roof. He saw Hickok arrive with four police officers. Hardin wrote in his autobiography, “Now I believed that if Wild Bill found me in a defenseless condition, he would take no explanation but would kill me to add to his reputation.”

Hardin leaped from the hotel roof into the street and hid in a haystack until daybreak. He then swiped a horse and rode to a cow camp 35 miles from town. Hardin then claimed that he killed lawman Tom Carson and two deputies. According to Hardin, he did not murder them but forced them to disrobe and walk back to Abilene. Hardin left for Texas the next day, never to return to Abilene.

In September 1871, Hardin was involved in a gunfight with two Texas Special Policemen, two freedmen, privates Green Paramore and John Lackey. During the gunfight, Paramore was killed, and Lackey was wounded. Subsequently, a Black posse from Austin, Texas, rode after Hardin, hoping to apprehend him for the murder of Paramore and the injuring of Lackey. Within a short time, the posse returned to Austin, “sadder and wiser” after Hardin ambushed and killed three posse members.

In early 1872, Hardin was in Gonzales County, Texas. At this time, Hardin married Jane Bowen and started hanging around with her brother, cattle rustler Robert Bowen. While in the area, he also renewed his acquaintance with some of his cousins who were allied with a local family, the Taylors, who had been feuding with the rival Sutton faction for several years.

On August 7, 1872, Hardin was wounded by a shotgun blast in a gambling dispute at the Gates Saloon in Trinity, Texas. He was shot by Phil Sublett, who had lost money to him in a poker game. Two buckshot pellets penetrated Hardin’s kidney, and it seemed as if Hardin would perish for a while.

While recovering from his wounds, Hardin decided he wanted to settle down. He surrendered to Sheriff Reagan in Cherokee County, Texas. Hardin was wounded in the right knee by an accidental gunshot from a nervous deputy. Hardin handed over his guns to Sheriff Reagan and asked to be tried for his past crimes to ” clear the slate.” However, when Hardin learned of how many murders Reagan would charge him with, he decided to renege on the deal. A relative smuggled a hacksaw to Hardin, who escaped after sawing through the bars of a prison window. In November 1872, Hardin escaped from the Gonzales County, Texas, jail despite a guard of six men. A reward of $100 was offered for his capture and arrest.

On May 15, 1873, Jim Cox and Jake Christman were killed by the Taylor faction at Tumlinson Creek. Hardin, who had finally recovered from the injuries sustained in Sublett’s attack, admitted that there were rumors that he had led the assaults in which these men were killed. Still, he would neither confirm nor deny his involvement: “…as I have never pleaded to that case, I will at this time have little to say….”

Hardin’s primary notoriety in the Sutton-Taylor feud came from his killing two lawmen known to be Sutton’s family allies. On July 18, 1873, in Cuero, Texas, Hardin killed DeWitt County Deputy Sheriff J.B. Morgan, who served under County Sheriff Jack Helm (a former captain in the Texas State Police and leader of the Sutton force at that time). Later that day, Hardin killed Helm in the town square of Albuquerque, Texas. On the run again in mid-1873, Hardin helped with the escape of his brother-in-law, Joshua Bowen, from the Gonzales County, Texas, jail where he was incarcerated on an 1872 murder charge. Allegedly, Hardin was also involved in the killing of Thomas Holderman.

On March 11, 1874, the Sutton-Taylor feud intensified when Jim and Bill Taylor murdered Billy Sutton and Gabriel Slaughter as they waited on a steamboat platform in Indianola, Texas. Tired of the feuding, the two planned to leave the area for good. Hardin confessed that he and his brother Joseph had been part (along with both Taylors) of the killings.

After a quick visit to Florida – where he maintained that he had been involved in three incidents against Black men, including a lynching – Hardin met with his wife, Jane, and their young daughter, with whom he had moved under the assumed name “Swain.” Hardin then met up with his “gang” on May 26, 1874, in a Comanche, Texas, saloon to celebrate his 21st birthday. Hardin spotted Brown County Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb entering the establishment. He asked Webb if he had come to arrest him. When Webb said he had not, Hardin invited him for a drink. As Webb followed him inside, Hardin claimed Webb drew his pistol. One of Hardin’s men yelled out a warning, and in the subsequent gunfight, Webb was killed. It was reported in the newspapers that Webb was shot as he was pulling out an arrest warrant for one of Hardin’s group. Two of Hardin’s accomplices in the shooting were cousins Bud Dixon and Jim Taylor.

The death of the popular Webb caused a lynch mob to be formed. Hardin’s parents and wife were taken into protective custody, while his brother Joe and two cousins, Bud and Tom Dixon, were all arrested on outstanding warrants. A group of local men broke into the jail in July 1874 and hanged Joe and the two Dixon boys. After this, Hardin and Jim Taylor parted ways for good. Hardin would assert that he twice repelled attackers connected to the feud that had come after him, killing a man each time. On November 18, 1875, the leader of the Suttons, ex-Cuero, Texas, town marshal Reuben Brown was shot and killed by five men in Cuero and a Black man named Tom Freeman, with another Black man being wounded. It is not known if Hardin was involved in the killing of Reuben Brown, as he makes no further mention of the incident in his autobiography.

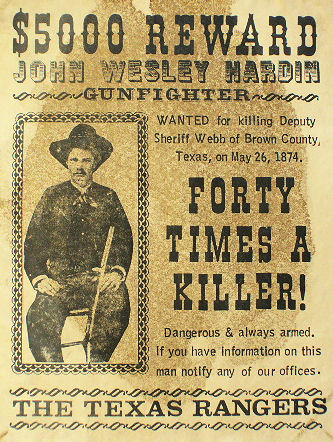

On January 20, 1875, Texas legislators authorized Governor Richard Hubbard to offer a $5,000 reward for Hardin’s arrest. An undercover Texas Ranger named Jack Duncan found information indicating that Hardin was hiding out on the Alabama-Florida border using the alias “James W. Swain.” In his autobiography, Hardin admitted that he had “adopted” the name of Texas Town Marshal Henry Swain, who had married Hardin’s cousin Molly Parks.

(Photo: A wanted poster for John Wesley Hardin, 1874. Wikimedia Commons.)

In 1877, two former slaves of his father’s, “Jake” Menzel and Robert Borup, tried to apprehend Hardin in Gainesville, Florida, to secure the large reward offered for his capture. Hardin killed one and blinded the other.

On August 24, 1877, Rangers and local police encountered Hardin on a train in Pensacola, Florida. He tried to pull his .44 Colt cap-and-ball pistol out, but it got caught up in his clothing. The officers knocked Hardin unconscious. They arrested two of his companions, and Texas Ranger John Armstrong killed a third man named Mann, who carried a pistol in his hand. Hardin maintained that he was captured while smoking his pipe and that Duncan found Hardin’s gun under his shirt only after he was arrested.

Hardin was placed on trial for killing Webb and, in June 1878, was sentenced to 25 years in Huntsville Prison. In 1879, Hardin and 50 other convicts almost successfully tunneled into the prison armory but were stopped cold. Hardin made several attempts to escape during his incarceration. On February 14, 1892, while serving his prison term, Hardin was convicted of manslaughter for the earlier murder of J.B. Morgan and received a two-year sentence to be served concurrently with his 25-year sentence.

Hardin eventually adapted to prison life. While there, he read theological books, became the head of the prison Sunday School, and studied law. He suffered from poor health, especially when the wound he had received from Sublett flared up and became re-infected in 1883, causing him to become bedridden for nearly two years. In 1892, he was described as 5 feet 9 inches tall and 160 pounds. Hardin had a fair complexion, hazel eyes, dark hair, and scars on his right knee, shoulder, left thigh, right side, hip, elbow, and back. On November 6, 1892, while in prison, his first wife, Jane, died.

While in prison, he wrote an autobiography. He wildly fabricated and exaggerated tales about his life. He claimed credit for many murders that cannot be confirmed.

Hardin was released from incarceration on February 17, 1894, after serving seventeen of his twenty-five-year sentence. He was forty years old when he landed in Gonzales, Texas. On March 16 of that year, Hardin was pardoned by the governor, and on July 21, he passed the state’s bar examination, obtaining a license to practice law. According to the newspapers in 1900, shortly after his release from prison, Hardin was arrested for negligent homicide when he made a small $5 bet that he could knock a Mexican man off a soapbox on which the man was relaxing, winning the bet but leaving the man dead from the fall and not the gunshot.

Hardin married 15-year-old Callie Lewis on January 9, 1895. The marriage did not last long, although it was never legally dissolved. Afterward, Hardin moved to El Pao, Texas.

An El Paso lawman, John Selman Jr., detained and arrested Hardin’s friend and part-time prostitute, the “widow” M’Rose, for “brandishing a gun in public.” Hardin challenged Selman, and the two men fought. Some witnesses maintain that Hardin pistol-whipped the younger man. Selman’s father, Constable John Selman Sr. (a notorious gunman and former outlaw), accosted Hardin on August 19, 1895, and the two men traded angry words.

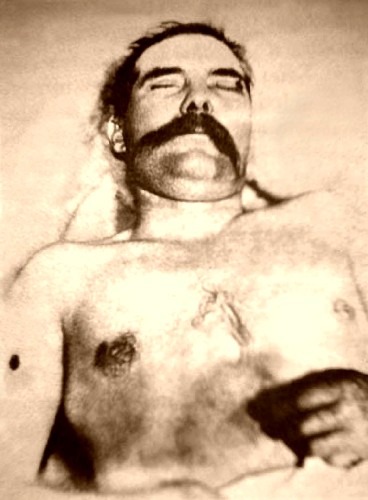

That same night, Hardin went to the Acme Saloon, where he played dice; his last words were “Four Sixes to Beat.” Shortly before midnight, Selman Sr. arrived at the saloon, strolled up to Hardin from behind, and put a bullet in his head, killing him immediately. As Hardin lay on the floor, Selman pumped three more bullets into him. Hardin was buried the next day in EL Paso.

Selman Sr. was arrested and stood trial for murder. He claimed self-defense, stating that he saw Hardin drawing his pistol upon seeing him enter the bar, and a hung jury resulted in him being released on bond, pending a retrial. However, before a retrial could occur, Selman was killed in a gunfight with U.S. Marshal George Scarborough on April 6, 1896, during a disagreement after a card game.

A century later, on August 27, 1995, there was a conflict between two factions at the site of Hardin’s grave. One group, representing several of Hardin’s great-grandchildren, wanted to relocate his body to Nixon, Texas, to be buried next to his first wife, Jane. The other group, made up of locals from El Paso, sought to prevent the move. At the cemetery, the group representing Hardin’s descendants presented a disinterment permit for the body, while the people from El Paso presented a court order prohibiting its removal. Both sides accused the other of desiring the tourist revenue the location of the body generated. The resulting lawsuit ruled in favor of keeping the body in El Paso.

(Photo: John Wesley Hardin’s post-mortem photo. Wikimedia Commons.)

Subscribe to History Daily with Francis Chappell Black to receive daily updates on new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment