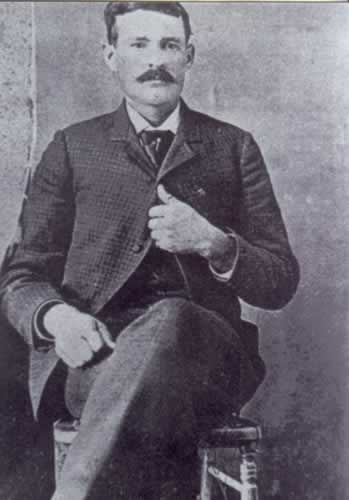

Image: “Black Jack” Tom Ketchum. (Wikimedia Commons.)

“Black Jack” Tom Ketchum was an American cowboy who later in life became an outlaw. He was hanged in 1901 for attempted train robbery. The execution was bungled; he was decapitated because the executioner used a rope that was too long, and the lubricated rope was too thin and cordlike.

Born on October 31, 1863, in San Saba County, Texas, Tom Kethum’s father, Green Berry Ketchum Sr., died when he was 48, and Tom was only five. His mother, Temperance Ketchum, suffered from blindness and died when Tom was ten. Tom was the youngest of eight children – six boys and two girls. Tom’s oldest brother, Green Berry Jr., became a rich, well-respected cattleman and horse breeder. Another brother, Samuel, married and had two children but abandoned the family when his children were young.

Tom and Sam labored as cowboys on ranches throughout Texas and New Mexico. On their many cattle drives, they became familiar with the territory and the settlers and ranchers in the area. They soon grasped that there were better ways to make money. At first, the two brothers had a propensity for mischief-making and petty thievery. But while their older brother, Berry, became one of the wealthy stockmen in Texas, Sam and Tom became robbers. Their lawbreaking only lasted five or six years. It cannot be determined with any certainty how many jobs the Ketchum brothers pulled off because they were only arrested in conjunction with just a few holdups. However, other crimes were attributed to them.

Tom’s first run-in with train robbing was in 1890 in Clayton, New Mexico, forty miles south of the Colorado border. He had just arrived there with a northbound trail herd from Roswell, and Tom hid behind a pile of railroad ties and sprayed the seat of a railroad engineer’s overalls with a peashooter as the trainman bent over to oil the drive wheels. When the engineer went for his gun, Tom escaped. That would be the most innocent prank that Tom would undertake. His first criminal act came on December 12, 1895, when he was part of the shooting of John Powers on Power’s ranch south of Knickerbocker, Texas. It was thought to be a murder for hire contracted by Powers’ wife, who was arrested. A grand jury indicted Tom, Dave Atkins, and Bud Upshaw, but they were nowhere to be found. When Tom got wind of the indictments, he headed for New Mexico, and Atkins and Upshaw fled to Arizona.

On June 11, 1896, Tom and Sam Ketchum robbed the Liberty, New Mexico, general store and post office owned by Levi and Morris Herzstein. Soon Levi and four other men were hot on the brothers’ trail. The Ketchums were finishing a meal when Herzstein’s posse roared down on them. When the shooting was over, Herzstein was dead, and the Ketchums had escaped, never to be charged in the killing.

Tom was given the nickname “Black Jack” after southern Arizona highwayman Will “Black Jack” Christian, who was killed in April 1897, even though the pair had only met once. Tom later tried to disown the “Black Jack” label because he felt that he and his gang would be held liable for some of Christian’s crimes. Tom, Will Carver, and Atkins began their train-robbing adventures two hours after midnight on May 14, 1897, just outside Lozier, Texas.

Ketchum and Carver clambered over the coal tender and, at gunpoint, ordered the train’s engineer, George Freese, to stop the train a mile ahead. Atkins was waiting with dynamite and had already severed the telegraph line there. The safe located on the train required three charges of explosives to blow, and the job took two hours, but the trio soon galloped toward New Mexico and their favorite Turkey Creek hideout with a loot bag bulging with $42,000. They settled into their hideaway, making irregular trips to Cimarron or Trinidad in Colorado. The men spent a leisurely summer at the hideout, resting and plotting their next move.

On September 2, 1897, the Ketchum brothers, Carver and Atkins, camped alongside the Union Pacific, Denver & Gulf tracks close to the village of Folsom in northeastern New Mexico. At 10 a.m. the following day, the Texas Express left Denver’s Union Station on its usual thirty-one-hour excursion to Fort Worth. At 9:10 p.m., the Express stopped briefly in Folsom, where two outlaws boarded the coal car undetected. The train continued its trip, and in its cars, passengers readied themselves for sleep. As the train slowed to make the grade at Twin Mountain, the two men entered the cab and ordered the engineer to stop on a large curve two miles ahead.

The two remaining robbers came aboard and set off their dynamite, but the safe would not open. Frustrated, one robber placed fourteen sticks of dynamite on the safe and put a side of beef on top of it to reduce the concussion. The huge explosion finally opened the safe. The outlaws vanished into the night, but this time, their haul was only between $2,000 and $3,000 and a batch of silver spoons. As soon as word of the holdup reached Folsom, posses from Clayton and Trinidad started in pursuit. Previously a quiet place, Northeast New Mexico was teeming with lawmen. By this point, the gang went their separate ways, with “Black Jack” remaining in southern New Mexico, pulling off a few post office stickups for pocket change and taking part in the occasional cattle roundup.

On December 7, 1897, the Ketchum brothers and the rest of their gang – Ed Cullen, Atkins, “Broncho Bill” Walters, and Carver – set their sights on a job at Stein’s Pass along the New Mexico-Arizona border. At the pass, they first robbed the Southern Pacific depot for a measly twelve dollars and twenty-five cents and a .44 Winchester. Tom and Broncho Bill cut the telegraph wires and rode down the railway line about a mile, where they built a fire on both sides of the tracks and secured the horses while Sam and the others waited at the station to take over the next train. Anticipating a stickup, the railroad stationed several guards on the train. The two sides exchanged gunfire for nearly half an hour, and Cullen was killed, his final words being, “Boys, I’m gone! Boys, I’m dead!”

The gang left the area without even boarding the train. Leaving Arizona and crossing New Mexico, the Ketchums, Carver, and Atkins made for Val Verde County, Texas, where the Bud Newman gang had made a good haul from the Southern Pacific train Number 20 nearly eighteen months earlier. The Ketchum gang decided to hit the same area, hoping that lightning would strike twice. On April 28, 1898, as Number 20 pulled out of the Comstock station, two of the Ketchum gang scrambled across the coal tender to the cab, forcing the train to stop, uncoupling the express car, and applying dynamite and a fuse. The huge explosion was so large that it blew a barrel-sized hole in the roof and splintered one side of the railcar. The thieves rummaged around in the wreckage, found the money, and disappeared – with no posse in sight.

In the summer of 1899, Tom’s disposition and temper finally caused the gang’s breakup. Atkins decided to reform, and even Sam Ketchum abandoned his brother. Carver threw in with Sam to create a new gang. Following several unsuccessful robberies as a new gang, Carver died in a shootout with Sheriff E.S. Briant of Sonora, Texas, on April 2, 1901. Sam and his crew had tried to rob the Texas Express out of Folsom for a second time on July 11, 1899. While the robbery proved moderately successful, a posse tracked down the gang, and Sam suffered a gunshot to the arm. After he refused to have his arm amputated, he succumbed to blood poisoning on July 24, 1899.

In the meantime, Tom stayed on his own and was unaware of the July 11 robbery and the death of his brother. He was planning a third holdup of the Texas Express at the exact location. Tom staked out the site at Twin Mountain on August 16, 1899, while awaiting the southbound Express. He jumped on the coal tender during the train’s brief stop in Folsom. About halfway to the Twin Mountain grade, Black Jack held up the engineer and fireman, asking them “if they would kindly stop when he told them to.”

In the baggage and mail car, postal clerk Fred Bartlett suspected something was wrong and looked out the door. Tom fired his rifle, hitting Bartlett in the jaw. Bartlett staggered to the day coach and gasped to conductor Frank Harrington, “Frank, I’m killed. They’re robbing the train again.” Bartlett survived his wounds, and Harrington, who had been on the train for both robberies, vowed to fight back if it ever happened again. He fired a shotgun at Tom, hitting him with eleven buckshot pellets just above the right elbow.

The train headed for Clayton, where the sheriff deputized a posse and headed to the scene of the robbery. The next day, a posse located Ketchum weakened from blood loss. He was taken to the Mt. Sam Rafael Hospital in Trinidad. There, doctors determined his arm was mangled beyond repair and decided to amputate. Tom attempted suicide by wrapping bandages around his neck so that he was taken to the Santa Fe prison, where the amputation was performed several days later without the benefit of anesthesia of any kind.

Ketchum stood trial in Clayton on September 6, 1900. At the end of the trial, Ketchum was convicted of attempted train robbery and condemned to death by Judge William Mills. The hanging was scheduled for October 5, 1900. Tom Ketchum was the only person ever hanged in Union County, New Mexico Territory. He was also the only person to be executed for the offense of “felonious assault upon a railway train” in New Mexico Territory. The law was later determined to be unconstitutional.

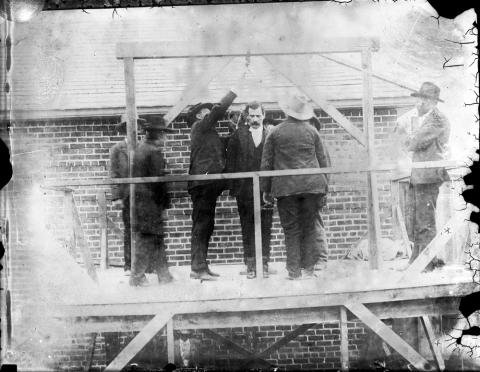

(Photo: Sheriff Salome Garcia of Union County, New Mexico, tightens the noose around the neck of Thomas “Black Jack” Ketchum prior to his hanging in Clayton, New Mexico. Also on the gallows are Sheriff O.T. Clark of Las Animas County, Colorado; Detective H.J. Chambers of Chicago, Illinois; Trinidad citizen C. de Baca; Dr. J.C. Clark; and a priest, Father Dean. The hanging would decapitate Ketchum. Wikimedia Commons)

Despite their total financial haul – estimated today at $100,000 to $180,000 – their associations through shared personnel with Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, and the fact that the Ketchums were feared from Colorado throughout the Southwest, they are remembered today less for their criminal activities than for how Tom Ketchum finally died. Indeed, Ketchum’s hanging would garner much more attention in the press than any other act in his criminal career. A fifteen-foot rope had been received from the police chief at Kansas City, who suggested a drop of seven feet at the gallows. Detective H.J. Chambers of Denver, who had been recruited to help Sheriff Salome Garcia as executioner, strongly contended that four feet six inches would be enough for a man of 193 pounds. During his incarceration, Ketchum’s weight ballooned to 215 pounds which the executioner did not consider. Lewis Fort, who represented the governor’s office, lengthened the rope to five feet six inches, inducing Garcia to extend it again to six feet before the whole group finally agreed to leave the rope at a length of five feet nine inches.

The San Francisco Chronicle recorded Ketchum’s final words as: “Goodbye. Please dig my grave very deep. All right; hurry up.”

Sheriff Salome Garcia gave a comprehensive view of the event:

“He walked firmly up the steps, saying as he went up, “Dig my grave deep, boys.” Stepping upon the trap door, he asked for the black cap, and it was placed on his neck, and while they delayed somewhat, he became impatient and said, “Let her go, boys.” ….The sheriff cut the trigger rope with a hatchet, and his body shot down with all its 215 pounds of weight. Everyone within or without the stockade held their breath, and their hearts gave a great bound of horror when it was seen that his head had been severed from his body by the fall. His body alighted squarely upon its feet, stood for a moment, swayed, and fell, and then great streams of red, red blood spurted from his severed neck as if to shame the very ground upon which it poured. The head rolled aside, and the rope, released, bounded high and fell with a thud upon the scaffold from whence it came.”

At the time, he was the only criminal ever decapitated during a judicial hanging in the United States. The only other recorded example was in England in 1601. Later, it happened again at the hanging of Eva Dugan in the Pinal County, Arizona, prison in 1930.

A famous postcard was made showing the body. After the debacle, his head was sewn back onto the torso for viewing, and he was buried at Clayton’s Boot Hill at 2:30 p.m. In the 1930s, his body was re-interred in the new cemetery in Clayton, where it remains to this day.

(Photo: Sepia-tone photo from a contemporary postcard showing Tom Ketchum’s decapitated body. The caption reads, “Body of Black Jack after the hanging showing head snapped off.” Wikimedia Commons.)

Subscribe to History Daily with Francis Chappell Black to receive regular updates on new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment