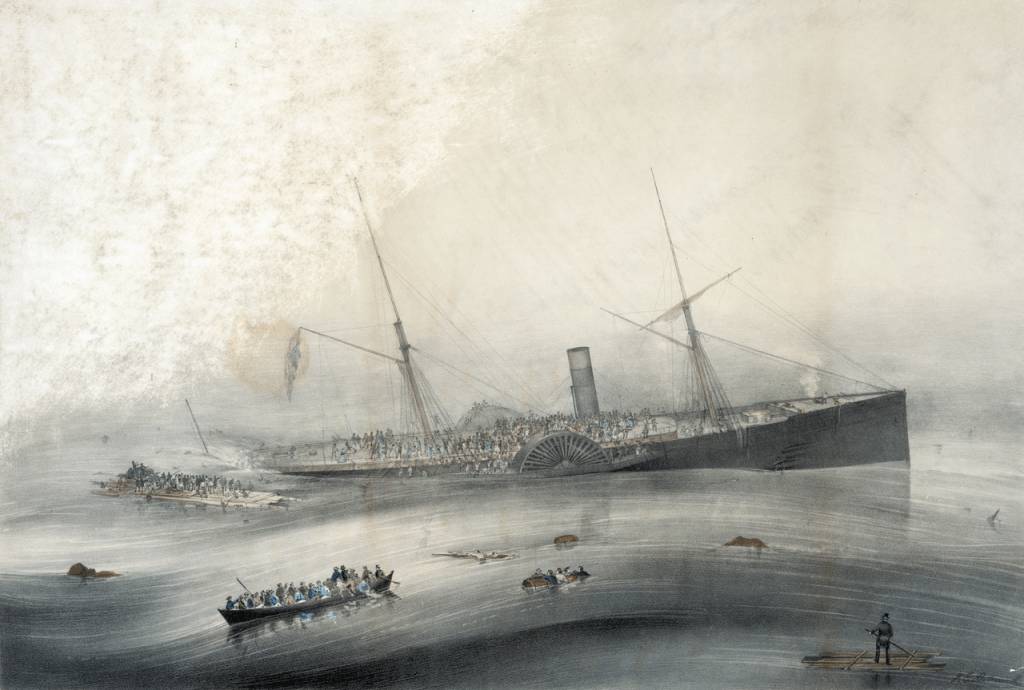

Original caption: “Wreck of the U.S.M. Steam Ship ‘Arctic’. Off Cape Race Wednesday September 27th 1854. On her homeward voyage from Liverpool, during a dense fog, she came in collision with the French iron propeller ‘VESTA,’ and was so badly injured that in about 5 hours she sunk stern foremost by which terrible calamity nearly 300 persons are supposed to have perished.” (Public Domain.)

On this day in history, September 27, 1854, while on the way to New York from Liverpool, England, the SS Arctic struck the SS Vesta, a far smaller fishing boat, 50 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, now a part of Canada. There were nearly 400 people on board Arctic – almost 250 passengers and 150 crew.

The Arctic was a luxury vessel built in 1850 to transport travelers across the Atlantic Ocean. It had a wooden hull and could hit speeds of nearly 13 knots, a remarkable pace at that time in history. On September 20, 1854, the Arctic left Liverpool, England, for North America. Seven days later, it sailed into heavy fog near the Newfoundland coast. Regrettably, the ship’s captain, James Luce, failed to exercise the regular safety procedures for dealing with fog – he did not decrease the speed of the Arctic, he was unable to sound the ship’s horn, and he did not increase the number of watchmen.

On September 27, the SS Arctic struck the SS Vesta in heavy fog, causing the death of 322 people. The Arctic was a passenger steamer ship launched in 1850 for the Collins Line. It was one of four ships the company built utilizing U.S. government subsidies to take on the British-backed Cunard Line. The Collins Line successfully sought financing as a mail and passenger ship to Europe in 1847. As part of the deal in obtaining the financial support, the Collins line granted that they could be brought into service as a troop transport or some other requirement in times of war.

The vessel launching in 1850 was well thought of at the time. She was considered one of the finest ships built up to that point, and thousands watched as she was launched at Brown shipyards on the New York East River. Because of her fast speed, she was called the “clipper of the sea.” Not only was she speedy but lavish with her fixtures and lodgings. Under captain James Luce, the ship undertook her sea trials and first routine maintenance without incident. In 1853, she ran ashore on Burbo Bank in Liverpool Bay while on her way to New York. She had to be refloated and sent back to Liverpool. In 1854 she collided with the Black Rock of the Saltee Islands from Liverpool to New York. Once again, she was refloated and sent to Liverpool. Arctic’s engines were costly to run, and they had to rely on an innovation by a Baltimore firm to lower expenses. The engines also put stress on the wooden hull as well.

On September 27, 1854, while traveling to New York from Liverpool, an unexpected and thick fog came up 50 miles from the coast of Newfoundland. Captain Luce failed to take the usual safety measures by slowing down, adding extra watches, and sounding the horn. At 12:15 p.m., the Arctic rammed into the iron-hulled French steamer Vesta. At first, Captain Luce thought the smaller vessel had been more severely damaged. Nevertheless, the iron-hulled ship had drastically damaged the Arctic instead, and it was sinking. Under the maritime rules of the time, the boat only had six lifeboats capable of carrying 180 people. Yet, there were 400 people aboard the Arctic – 250 passengers and 150 crew.

Discipline among the crew and passengers broke down rapidly as many rushed for the few available lifeboats. No “women and children first” rule was implemented. Most of the crew got into lifeboats, against the orders of Captain Luce and the more non-disabled passengers, including the French ambassador, the Duc de Gramont, who was seen leaping from the boat into one of the last lifeboats. Those that remained had to use makeshift rafts or could not leave the vessel and went down with her when the Arctic sank four hours after the incident began. Captain Luce went down with the ship but survived the sinking – his 11-year-old son would not be so lucky. Two of the lifeboats made it to land. Another steamer picked another up. The other three lifeboats were never seen again. In the meantime, the Vesta, which appeared to have sustained mortal damage, was saved from sinking by her watertight bulkheads and made it to the harbor at St. John’s, Newfoundland.

The deaths were shocking as all the women and children succumbed, including the wife of Edward Collins, founder and owner of the Collins Line, and two of his children aboard at the time. Other prominent people also perished, including Captain Luce’s 11-year-old son Willie. Lost as well was a rare copy of William Shakespeare’s First Folio. News of the sinking did not reach New York until two weeks later due to limited telecommunications. The information brought an outpouring of anger in newspapers and public opinion. There were calls for an inquiry and to change the law about the number of lifeboats required. They were never acted upon, and no one was ever held to account. Captain Luce was not generally considered at fault but retired after the incident. The outrage of so many mutinous crew surviving instead of women and children would result in many surviving crew members not returning to America.

The Collins Line suffered further after this incident. The SS Pacific vanished in 1856 in transit to New York from Liverpool. Many believe it struck an iceberg and sank as it raced to arrive quicker than the Cunard Line Persia. All 55 passengers and 141 crew were lost along with their fright. Her remains were found in 1993 off Wales (some dispute this), and alternative theories about her fate have been put forward. The SS Adriatic was launched on April 7, 1856, but did not do her sea trials until 1857. However, due to an economic depression, Congress reduced the subsidy to $385,000. In February 1858, the line suspended operations and, in April, went into bankruptcy. All its remaining vessels were auctioned off, and the company paid off its creditors. That left Cunard, for a time, with little opposition in the passenger trade between Europe and the United States.

Subscribe to History Daily with Francis Chappell Black to receive regular updates via email:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment