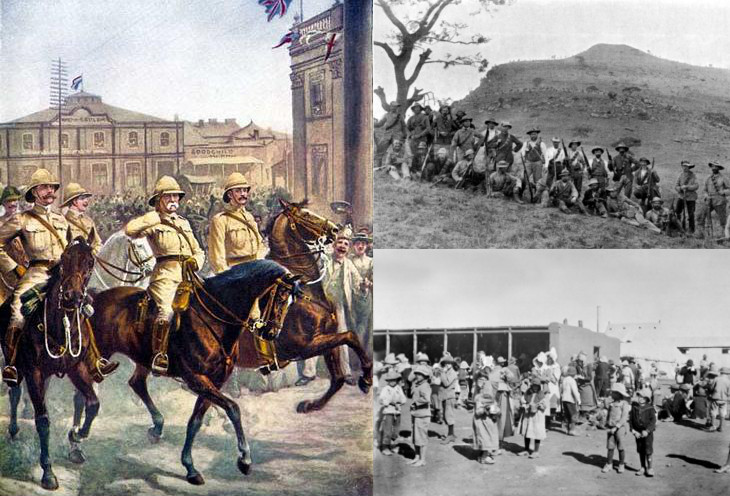

Image: Clockwise from left: Frederick Roberts entering in Kimberley; Boer militia at the Battle of Spion Kop; Boer women and children in a British concentration camp. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, October 11, 1899, the Second South African Boer War began involving Britain and the Boers of the Transvaal and Orange Free State.

The Boers, also identified as Afrikaners, were the ancestors of the original Dutch colonists of southern Africa. Britain took control of the Dutch Cape colony in 1806 during the Napoleonic wars, initiating opposition from the freedom-loving Boers, who hated having Britain in South Africa and Britain’s anti-slavery stance. In 1833, the Boers began migrating into African tribal territory, creating the Transvaal and the Orange Free State republics. The two new republics lived amiably with their British neighbors until 1867, when the detection of diamonds and gold in the territory made fighting between the Boer states and Britain predictable.

After the discovery of gold in the Boer republics, there was an enormous invasion of “foreigners,” primarily British, from the Cape Colony. They were not authorized to vote and were viewed as “unwelcome visitors,” intruders, and they complained to the British authorities about the situation. Mediations collapsed, and in the beginning period of the war, the Boers effectively attacked British outposts before being thrust back by British forces. Though the English quickly seized the Boer republics, many Boers declined to admit defeat and participated in Guerrilla warfare. Ultimately, British scorched earth practices and the horrid circumstances experienced in concentration camps by Boer women and children, brought the remaining Boer guerrillas to the bargaining table, terminating the war.

The war started in 1899 after the collapse of the Bloemfontein Conference when Boer forces assaulted colonial outposts in nearby British territories. Beginning in October 1899, the Boers placed Ladysmith, Kimberley, and Mafeking under siege, and earned a series of triumphs at Colenso, Magersfontein, and Stormberg. In reply to these advances, additional British soldiers were moved to Southern Africa, and mainly mounted ineffective strikes versus the Boers. Nevertheless, British fate shifted when their superior officer, General Redvers Buller, was substituted by Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener, who freed the three besieged cities and attacked the two Boer Republics in early 1900 at the command of a 180,000-strong military force. The Boers, alert that they could not resist such a vast army, gave Britain possession of their republics.

Boer politicians escaped the region; the British Empire formally seized the two republics in 1900. In Britain, the Conservative government, led by Lord Salisbury, endeavored to exploit British military victories by calling an early general election, nicknamed by observers as a “khaki election.” Nonetheless, many Boer warriors began a guerrilla struggle against the British Army. Commanded by leading generals such as Jan Smuts, Louis Botha, Christiaan de Wet, and Koos de la Rey, Boer guerrillas started a strategy of ambushes and hit-and-run attacks against the British, which would continue for two years.

The Boer guerrilla strategy was hard for the British to overcome, precisely because the British were unaware of guerrilla tactics and the comprehensive support the guerrillas had amongst the residents of the Boer Republics. In reaction to persistent failures to conquer the Boer guerillas, British generals ordered scorched earth policies to be executed as part of a more extensive and multi-faceted pacification operation. British soldiers perpetrated numerous war crimes and were instructed to destroy farms and kill livestock to prevent them from being used by Boer guerrillas. More than 100,000 Boer citizens (primarily women and children) were effectively forced into concentration camps, where 26,000 mainly died of starvation and disease. Black Africans were also imprisoned in the camps to stop them from giving aid to the Boers; 20,000 died in the concentration camps as well.

The British concentration camps in the Boer War were first used for refugees evacuated by the conflict. Yet, as time passed, the camps became places where Boers and Africans deemed antagonistic towards the British cause in South Africa were interned. More particularly, the camps were primarily used for women and children because many interned men were shipped abroad. Many Boer and African prisoners were treated poorly in the camps, with many dying from disease and malnutrition. There were 45 camps for the Boers and another 64 for the Africans. It is projected that about 26,000 women and children perished in the camps. The British were universally condemned for the inhumane treatment of people in the camps. Emily Hobhouse, a British feminist and pacifist, prominently worked for better living conditions in the concentration camps and brought the issue to the forefront of the British public.

As well as these scorched earth policies, British cavalry units were sent to find and engage Boer guerrilla units; by this phase of the fighting, the actions being fought were minor scuffles. Few fighters were ever killed in these skirmishes, with most deaths due to disease. Lord Kitchener offered generous surrender terms to remaining Boer leaders to end the war. Wanting to guarantee their Boer compatriots were freed from the concentration camps, most Boer commanders agreed to the British conditions in the Treaty of Vereeniging, officially admitting defeat in May 1902. The two republics were converted into the British provinces of the Transvaal and Orange River, and in 1910 were brought together with the Natal and Cape Colonies to create the Union of South Africa, an autonomous dominion within the British Empire.

The British Army was helped considerably by colonial armies from the Cape Colony, the Natal, and Rhodesia, as well as more significant numbers of soldiers from the British Empire, particularly Canada, Australia, India, and New Zealand. Late in the war, Black African recruits contributed increasingly to the British war effort. International public opinion was friendly towards the Boers and harsh towards the British. Even within Britain, there was substantial disapproval of the conflict. Consequently, Boer forces drew many volunteers from neutral countries worldwide.

Ultimately, the Boer War was a destructive conflict at the pinnacle of European imperialism in Africa. Because of this, historians see the Boer War as an illustration of European colonization and the wars that developed as a consequence. The conflict led to the deaths of approximately 22,000 British soldiers (including from colonial armies) and over 6,000 Boer fighters. Thousands more civilians were victims of the war, all suffering terribly from disease and the effects of the concentration camps.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment