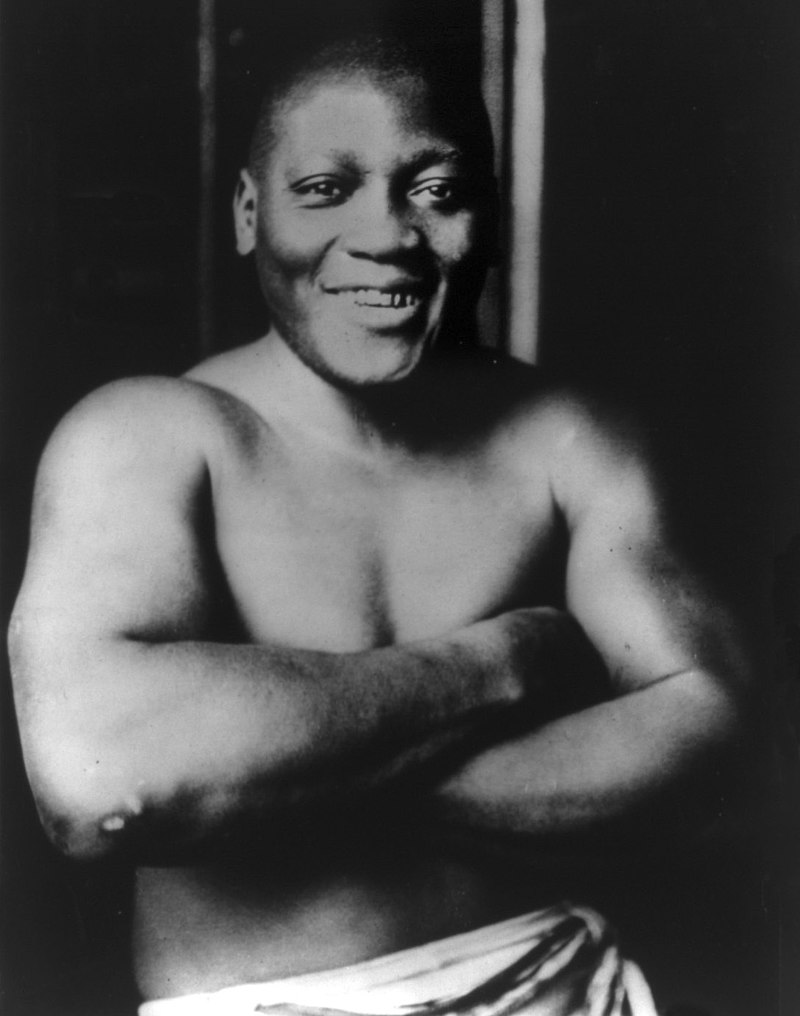

Image: Jack Johnson in 1915. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, October 18, 1912, Black boxer Jack Johnson was arrested for violating the Mann Act for “transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes” due to his relationship with white woman Lucille Cameron, who was allegedly a prostitute. He was later convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to a year in prison for his previous involvement with another white woman even before the Mann Act became law.

He was renowned as the Galveston Giant – a boxer who boxed his way to the first world heavyweight title held by an African American. But in 1912, Jack Johnson became known as a wanted man. Charged with breaking the Mann Act, which outlawed women’s movement across state lines for “immoral purposes,” Johnson’s interactions with white women caused him misfortune with the law.

Johnson was not the only person influenced by the Mann Act. Also known as the White-Slave Traffic Act of 1910, the law was used repeatedly to penalize Black men for their interactions with white women – dealings that dared to oppose the racial status quo. Entrenched in worries about women’s growing ability to move about the country and racist portrayals of the sexual cravings of Black men, the law was created to defend women against the imaginary plague of “white slavery,” a term used to refer to sex trafficking in the early 20th century.

Even though it has been substantially revised since 1910, the law, which was also used against men like Chuck Berry and Charlie Chaplin, is still in force today.

Johnson, then one of the most recognized Black men in America, was one of the Mann Act’s first casualties. When he defeated a white boxer, unbeaten heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries, in a highly advertised fight in 1910, it sparked race riots. It also made the authorities look more robustly at Johnson, famous for his extravagant conduct and prolific spending. His behavior had long irritated those who believed that an African American man should know his “place” and stay in it – and Johnson’s unabashed interactions with white women were seen as a slap in the face to racial norms.

Then, in 1912, prosecutors got their chance to administer the Mann Act when Lucille Cameron’s mother alleged that Johnson had abducted her daughter and carried her across state lines. Her mother also asserted that her daughter was insane. Nonetheless, Johnson was in a consensual liaison with Cameron and would shortly marry her; prosecutors used the claim as an excuse. As Chicago police detained him for kidnapping, federal prosecutors convened a grand jury to examine his interactions with white women.

There was just one problem – Cameron, who was in love with Johnson, refused to testify against him. Then, prosecutors discovered that Cameron had once been a prostitute, which destroyed her credibility as a witness. They dropped the case in the meantime, but not before the public found out.

The “white” public felt that because Johnson was of such poor character, it was their responsibility to ruin him any way they could. Prosecutors soon decided on another way to impose the Mann Act. This time, a woman, another alleged prostitute named Belle Schreiber, with whom he had been entangled with in 1909 and 1910, agreed to testify against him. In the courtroom, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the future Commissioner of Baseball who prolonged the baseball color barrier until his death, Johnson was deemed guilty by an all-white jury in June 1913, despite the truth that the events used to find him guilty took place before the passing of the Mann Act. He was condemned to a year and a day in prison.

Johnson skipped out on bail and left the United States, joining Lucille in Montreal on June 25 by pretending to be a member of a Black baseball team. From there, he fled to France. They lived in exile in Europe, Mexico, and South America for seven years.

Because of the case’s notoriety, legislators-initiated bills to ban marriage between black and white people in several states. Even though none of the proposed bills were passed, the attempts show how worried the country was about Johnson’s interracial relationship and his assumed “crime.”

Johnson spent some time in exile defending his heavyweight title but was beaten by white boxer Jess Willard in a fight in Cuba in 1915. Johnson finally returned to America on July 20, 1920. He gave himself up to federal agents at the Mexican border. He was dispatched to the United States Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, to begin serving his sentence in September 1920. He was released from custody on July 9, 1921.

After his release from prison, he tried to renew his career but struggled to remain significant in the boxing world.

In the meantime, the Mann Act continued to stay in effect. During the first half of the 20th century, the law was mainly used to prosecute men crossing state borders with underage girls or during premarital or extramarital affairs. In 1944, for example, Charlie Chaplin was charged – and eventually found innocent – for providing train fare for his girlfriend, Joan Berry, to take her across state lines within the bounds of a consensual relationship in 1941.

The law also continued to be an effective means against Black men whose relationships with white women enraged white supremacists. In 1959, Chuck Berry was prosecuted under the Mann Act for hiring – and allegedly starting a sexual relationship with – a 14-year-old white girl, Janice Escalanti. A Mann Act indictment and three trials ensued. For years, Berry refuted that he went to prison, but his fans and biographers could not overlook the accusation or the guilty verdict.

These days, the Mann Act is still on the books, though it’s been stripped of gender-specific language and revised to explain that it’s only relevant to sexual activity that’s deemed criminal. That stopped its use to penalize adulterous affairs and “immoral” conduct like premarital sex and interracial relations. But even though its implication has been replaced, the legacy of the Mann Act continues.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment