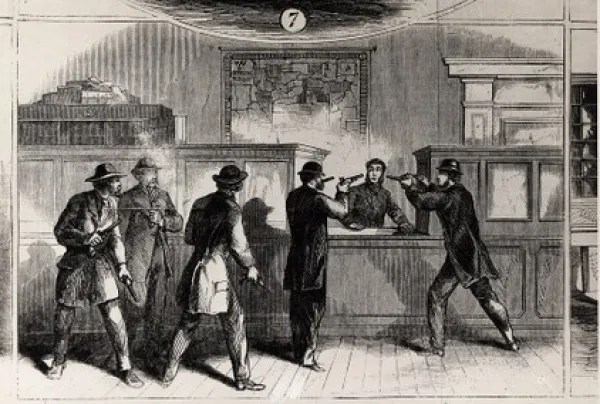

Image The Confederate raiders stick up the bank in St. Albans. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, October 19, 1864, twenty-two Confederate soldiers entered St. Albans, Vermont, from Canada, intent on robbing three banks to secure funds for the depleted treasury of the Confederacy. The raid was designed to create havoc for this New England town as the invaders planned to burn the village to the ground, but things did not quite work out that way.

The St. Albans Raid remains the northernmost military action during the American Civil War.

The raid occurred on October 19, 1864, and was commanded by a young Confederate cavalry officer named Bennett Henderson Young. In the summer before the attack, 1st Lieutenant Young was sent by the Confederacy to Canada to survey the northern territory of the U.S.

Canada was neutral during the Civil War. The country allowed civilians and soldiers from the Union and the Confederacy to enter its borders to secure supplies or safety. Both sides conducted clandestine operations from Canada.

Young welcomed his mission eagerly. He wanted to punish New England for its part in the war and the destruction its Union soldiers had created throughout the South. Young did not think it reasonable that almost every town in the South lived in fear of wartime aggression. At the same time, many in the North existed without such anxiety, particularly those in New England.

In October 1864, Young convened with Confederate organizers in Toronto. He told them he had chosen to attack St. Albans, Vermont, a town in the northwest corner of the state.

St. Albans made a perfect target for several reasons: First, the town served as the headquarters of the Central Vermont Railroad. Because of that, the townsfolk were accustomed to seeing strangers in their midst. This would allow Young and his crew to penetrate the town with little suspicion.

Second, as a railroad hub, St. Albans was a prosperous town. Its three banks would have plenty of money in their vaults available for Young and his men to steal.

The Confederates wanted their group of brigands to bring the reality of war home to the people of New England. Young’s attack was meant to unnerve the Yankees and make them live in fear that Confederate raiders might attack them at any moment. Nonetheless, Young’s main reason for the operation was to gather funds for the Confederacy.

The third reason for choosing St. Albans was that it was situated in the northwest corner of the state, and Young and his raiders could easily make their way to Canada safely after the operation.

The twenty-two men arrived in St. Albans alone or in pairs over several days. They stayed in different hotels so as not to provoke apprehension. Their plan succeeded; no one in St. Albans guessed their plan.

The raid began at 3:00 p.m. on October 19, 1864.

The Confederates separated into three groups, and each faction entered a separate town bank. In each bank, the Confederates raised their pistols. They informed the tellers and customers that they were Confederate soldiers who had arrived to take St. Albans and its money for the glory of the Confederacy.

The raid lasted 25-30 minutes in total.

After they robbed the banks, the soldiers gathered all the horses in town. The rest of the St. Albans residents became aware of what was happening as the Confederates did this. The residents marched to the town square with their motley collection of firearms.

A violent firefight resulted.

The civilians shot three of the raiders. The Confederates killed one civilian, an out-of-town visitor named Elias Morrison. Ironically, Morrison had been a Confederate sympathizer.

After the firefight, Young and his men dashed out of town. As they rode away, they threw bottles of “Greek Fire” onto the sides of St. Alban’s buildings. Luckily for the inhabitants, the fire mostly smoldered. The only building claimed by Young’s fire-bombing was an outhouse.

Young and his raiders absconded with almost $227,000 from the banks. Shortly after crossing into Canada, Canadian police apprehended 14 of the attackers and about $90,000 of the stolen money. A Vermont posse captured Young.

Upon his arrest, Young claimed combatant status. The Vermonters were not having any of that. They tossed Young into a wagon and headed back to the United States. However, before they crossed the border, Canadian police stopped them and arrested Young.

Despite promising the Vermonters that they would return Young and his men to them the next day, they failed to do so. They decided to keep them in Canada to face an extradition trial.

The Confederates may have failed at torching St. Albans but initiated a wave of panic and anxiety throughout Vermont. Rumors spread like wildfire throughout the state that Confederates were attacking towns and cities like Burlington.

Vermonters questioned drifters and other unfamiliar persons who entered their town. The state government created a cavalry unit to patrol its borders; the only available men to serve in it were disabled soldiers.

In the interim, the Canadians sent the Confederates to Montreal, where a judge would decide whether to deport them back to the United States. In mid-December, the judge agreed that he did not have jurisdiction to settle the case. They released Young and his men.

American officials had them rearrested in short order based on charges of robbery. Young and his men had robbed individuals, which they argued was an extraditable crime.

The Vermonters’ luck in Canada had run out.

By late March 1865, the Canadian courts ruled that the raiders were not, in fact, eligible for extradition. This decision could have been a bit of revenge for how Vermonters supported the 1838 Patriot rebels against the Canadian government. Whatever the reason, the Canadians set Young and his men free.

The Confederates got away with a sizable portion of the $227,000 they stole from the St. Albans banks. The banks and their account holders lost all but 1/3rd of the money, which the Canadian authorities returned to the town.

Some of the stolen money reached the Confederate capital in Richmond, Virginia, but it arrived too late to do any good. The war was finished in April 1865.

Some historians suspect that numerous raiders used their earnings to start new businesses and careers at the war’s end. Many raiders returned to Kentucky and the South, becoming bankers and prominent businessmen.

Between 1865 and 1868, Young roamed around Canada and Ireland; the United States had a bounty on his head. In 1868, he returned to Kentucky, settled in Louisville, and opened a successful law practice. He died in 1919 at 75 years old. The citizens of Louisville remember him as a soldier, philanthropist, and gentleman.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment