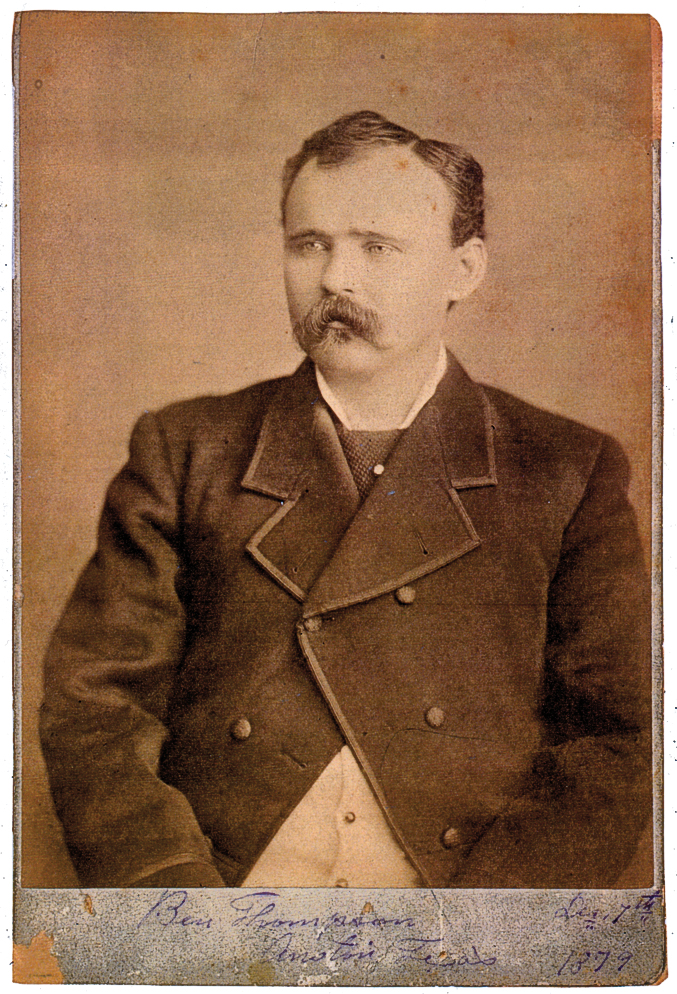

Image: Ben Thompson, 1879. (Public Domain)

“I always make it a rule to let the other fellow fire first. If a man wants to fight, I argue the question with him and try to show him how foolish it would be. If he can’t be dissuaded, why then the fun begins, but I always let him have the first crack. Then when I fire, you see, I have the verdict of self-defense on my side. I know that he is pretty certain, in his hurry, to miss. I never do.”

Ben Thompson

Ben Thompson was a gunman, gambler, and part-time lawman of the Old West. He was a counterpart of “Wild Bill” Hickok, “Buffalo” Bill Cody, John Wesley Hardin, and Bat Masterson, some of whom thought of him as a friend, others as an enemy. Thompson fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War and later for Emperor Maximilian in Mexico. After he was hired in 1881 as marshal in Austin, Texas, the crime rate dropped distinctly. Thompson was murdered at 40 in San Antonio, Texas, in the “Vaudeville Theater Ambush.”

Ben Thompson was born in Knottingley, Yorkshire, England, in 1843 and moved with his family to Austin, Texas, in 1851. As a boy, he labored in the printing industry, though his most influential education was gaining the skills to survive in the harsh Texas frontier. As it turned out, he was a very quick study. He learned to use a gun at an early age, and he possessed a temper that was as quick as his draw, and at fifteen, he wounded another boy who had made insulting comments about his shooting ability. He also developed his own moral code, which occasionally caused him to use his skills to defend others. While working in New Orleans, he came to the assistance of a woman who was being attacked, and he killed her assailant in a knife fight.

At the beginning of the Civil War, Ben Thompson signed up with John Rip Ford’s Second Cavalry, eventually participating in the battles of Galveston Bay, where he was injured, and the Confederate’s loss at La Fourche Crossing, Louisiana. His career in the Confederate Army ended abruptly in May 1865 when he killed a teamster in Austin after a dispute over an army mule. Thompson was arrested and promptly broke out of jail and escaped to Mexico. Always a firm believer that when God closes a door, He opens a window, Ben joined the army of Emperor Maximilian and fought for him until his empire fell in 1867. With his options running out in Mexico, Thompson returned to Texas, where he was arrested and sentenced to four year’s hard labor at Huntsville Penitentiary. However, two years later, his conviction was invalidated by President Grant.

Hoping for a change of luck, Thompson left Texas and went to Abilene, Kansas. His time in Kansas coincided with the heyday of the Texas cattle drives, and not being one to pass up a good opportunity, he opened a saloon with friend and fellow Civil War veteran Phillip Coe in 1871. Thompson was later injured in a buggy accident that also wounded his wife and child. While Ben was recovering, his partner was killed in a gunfight with Abilene Marshal Bill Hickok. The nature of the dispute is unclear, yet with “Wild Bill,” it could have been anything from a severe violation of the law to a minor disagreement over a hand of cards. Once again, circumstances turned against Thompson, and by 1874, he had returned to Texas and was making a living as a gambler.

On December 25, 1876, Ben was at Austin’s Capital Theatre when a melee broke out. Thompson was trying to assist one of the mischief-makers when theatre owner Mark Wilson shot at him. Thompson fired back at Wilson, killing him, though he was found to have shot in self-defense. Since arriving in the United States, Thompson had been required to grow up faster than expected, and he had ample grit and courage and could hold his own against the most violent individuals that the West had to offer. His capacity for survival left little time for building wealth or even a stable life for his family.

Always tempted by the lure of easy money, the Leadville silver strike brought Thompson to Colorado in 1879. He connected with a group of gunmen led by “Bat” Masterson, employed by the Atchison, Topeka, and Sant Fe Railway in their right-of-way dispute with the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. With the money he received from the railroad, Ben could return to Austin and open another saloon. However, his hope of finally settling down to enjoy an everyday family life was soon extinguished permanently.

With a reputation as an honest and generous businessman and a fast and deadly gun, Ben Thompson was twice elected as Austin City Marshal. In 1882, his primary vocation as a gambler interfered with his job as town marshal when he killed Jack Harris, the owner of the Vaudeville Variety Theatre, during an argument over a game of cards.

Theatre owner Jack Harris had led San Antonio’s “sporting crowd.” From Ireland, Harris emigrated to Connecticut, then moved to Texas. He had worked for the San Antonio Police Department and then served during the Civil War in the Confederate Army. After the war, Harris may have served Emperor Maximilian during the Franco-Mexican War, but although it has been claimed, it has never been confirmed. In 1868 Harris rejoined the police force and purchased a saloon with a partner, selling his half of the establishment in 1872. With his profits, he opened his own saloon, first calling it the Jack Harris Bar and Billiard Room but then changing the name to the Vaudeville Variety Theatre. It quickly became the most popular place in San Antonio and was the lynchpin of the Sporting District, the city’s red-light district.

Harris knew gunman Ben Thompson from their service in the army. In 1880, Thompson would frequent the Vaudeville Theatre, gambling heavily alongside Harris’ partner, Joe Foster, and with Thompson mostly losing. Thompson left in a “bad mood,” and although it was stated that he made threats, that has never been proven. Thompson returned to Austin, where as well as being Chief of Police, he owned the Iron Front Saloon. Harris and Foster told Thompson he was no longer welcome in the Vaudeville Variety Theatre. Thompson simply ignored the directive and returned to the establishment on July 11, 1882. Vaudeville Variety Theatre manager Billy Simms met Thompson on the street and tried to persuade him from going inside the Vaudeville, but to no avail. Thompson entered and told the bartender to inform Foster and Harris that he intended to “close this damn whorehouse.” Although it can be interpreted differently, he most likely meant that he intended to stay all night there rather than meaning it literally.

Thompson had a drink with jeweler Leon Rouvant, then left. Meanwhile, Billy Simms went upstairs and put on his guns, and warned Harris, who then went and grabbed a shotgun and placed himself behind a screen in view of the front door, where he waited for Thompson for at least ten minutes. Thompson had gone outside, visiting people on the street that he knew. Thompson returned and stood just outside the doorway and saw Harris with the shotgun but said nothing at first. After a few moments, with Harris still watching Thompson, the latter finally said, “What are you going to do with that shotgun, you damned son of a bitch?” To which Harris replied, “You kiss my ass, you son of a bitch!”

Within seconds, two shots were fired. One eyewitness later stated that after the verbal exchange, it was one or two minutes before the shots were fired, but in actual fact, it was only a couple of seconds. According to other witnesses, Thompson had seen Harris but did not initially enter the saloon. Instead, he waited, watched, allowed two ladies to enter by holding the doors for them, then passed the before-mentioned verbal exchange, after which the two shots were fired almost immediately.

Having not discharged his shotgun, Harris staggered, went upstairs, then collapsed. A doctor was summoned to which Harris is supposed to have said, “He took advantage of me and shot me from the dark.” However, this was not entirely true. Although Harris never fired, he was armed openly, and the area was lighted. Thompson was standing just outside the doorway, which was darkened, but Harris’ stance of producing and brandishing the shotgun put Harris at a distinct disadvantage, as it was a clear-cut case for self-defense on the part of Thompson.

Further, although Thompson was standing in a more darkened area than Harris, there was nothing to suggest it was a planned point from which to fire; it simply was where he happened to be located. Thompson then returned to his room at the Menger Hotel, where he remained the rest of the night without being approached by police. The following morning, he turned himself into Bexar County, Texas, Sheriff Thomas McCall and San Antonio Police Chief Sheridan.

When Thompson killed Harris, a written battle of words began between two newspapers, the San Antonio Light and the Austin Statesman, one demanding justice for Harris, the other defending Thompson. Newspapers from around the state fell into one or the other sides in the newspaper dispute. Many citizens in San Antonio believed that the town was better off without Harris, while others condemned Thompson as a murderer. An indictment was handed down on September 6, 1882. Although a change of venue was contemplated, by that time, popular opinion was leaning in Thompson’s favor, so the case was tried in San Antonio. Thompson was acquitted on January 30, 1883, in the subsequent trial that followed. This caused bad feelings from many citizens in San Antonio, especially those who were close friends of Harris. Friends of Thompson cheered outside the courtroom when the verdict was announced, and upon his return to Austin, he was met by a large crowd of well-wishers.

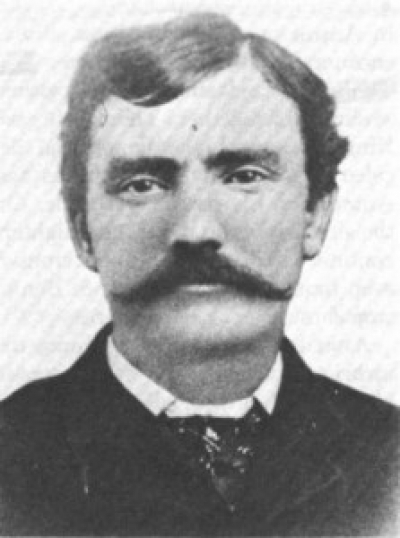

(Image: Ben Thompson while acting as Marshal for Austin, Texas. 1880. Public Domain.)

His warm reception may have given Ben a sense of overconfidence that trumped his own instinct for survival. On March 11, 1884, while in San Antonio on business, noted gunslinger King Fisher met up with his old friend Ben Thompson, also visiting town on business. Thompson was still very unpopular in San Antonio after the death of Harris. A battle over that killing had been brewing ever since between Thompson and friends of Harris, including Joe Foster. King Fisher would, it happens, become a victim in a situation, not of his making – he was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time.

On March 11, Fisher and Thompson appeared at a play at the Turner Hall Opera House, and later, at around 10:30 p.m., they went to the Vaudeville Variety Theatre. A local lawman named Jacob Coy joined them at their table. Thompson wanted to see Joe Foster, the theater owner and friend of Harris’s who was now partnered with Billy Simms and who was one of the main people driving the ongoing vendetta. Thompson had already spoken to Billy Simms, with whom he had had an amiable and almost cordial conversation.

Despite the feud and the general dislike for Thompson felt by many in San Antonio, both he and Fisher were feared men. Their reputations as gunmen and their having proven their skills in that realm many times made anyone wishing to face them to give pause. This is probably why Thompson’s enemies ambushed him rather than confronted him face-on.

Fisher and Thompson were brought upstairs to meet with Foster. Coy and Simms joined them in the theater box. Foster refused to speak with Thompson. Fisher allegedly noticed that something did not feel right about the situation. Simms and Coy stepped aside, and as they did, Fisher and Thompson leaped to their feet just as gunfire erupted from another theater box, with a burst of bullets hitting both Thompson and Fisher. Thompson fell onto his side, and Foster ran up and shot him in the head. Thompson returned fire with two shots, dying almost immediately afterward. Fisher was shot thirteen times and did fire one round in retaliation, wounding Coy. Coy was left disabled for life and never fully recovered.

While trying to draw his own pistol at the beginning of the altercation, Foster shot himself in the leg. Foster was taken down the street for medical attention, and his leg was amputated, but he died of blood loss during the operation. The exact narrative of the events that night is conflicting, as it was totally dependent on anti-Thompson witnesses or the attackers themselves. At first, the attackers tried to assert that Thompson and Foster had argued and that Thompson had drawn his gun on Foster, prompting Foster to draw, which resulted in an open gun battle. That, however, was disproved with time. What is known is that the two gunmen were ambushed with no foreknowledge of the attack, which negated any self-defense claims by the attackers.

There was a loud public outcry for a grand jury indictment of those involved, not only from Austin and other parts of Texas but from many inside San Antonio, who felt the ambush was gutless. However, no action was ever taken by the authorities. The San Antonio Police and the state prosecutor showed little interest in prosecuting the case, and eventually, it simply faded away. Fisher was interred on his ranch. His body was relocated to the Pioneer Cemetery in Uvalde, Texas. Thompson’s body was returned to Austin, and his funeral was one of the largest in Austin’s history at that time. His hometown gave him a monumental farewell, sixty-two carriages making up the procession. He was laid to rest in Austin’s Oakwood Cemetery on Thursday, March 13, 1884. His wife, two children, brother Billy and two sisters survived him. His wife Catherine remarried and moved to Paris, Texas. The date of her death and burial place remains unknown. His son, Benjamin, died in 1893, and his brother Billy died from natural causes in 1897. Ben’s daughter Kate received a college education and was raised to adulthood by his sister, Mrs. Mary Jane Thompson.

(Image: King Fisher. Public Domain.)

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment