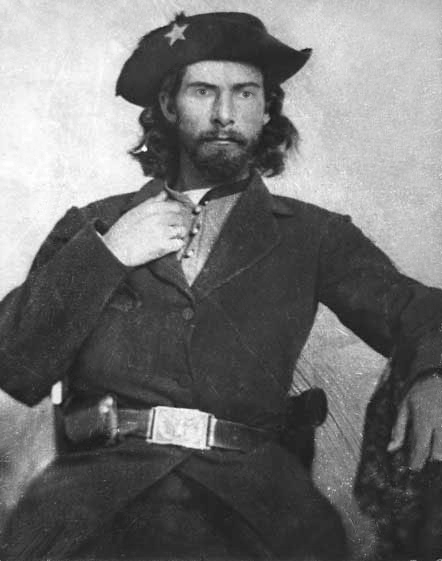

Image: William “Bloody Bill” Anderson. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, October 26, 1864, the infamous Confederate guerilla leader William “Bloody Bill” Anderson was killed outside Albany, Missouri, in a Union ambush. The dead body of the “blood-drenched savage,” as he became known, was positioned on public display. Anderson kept a rope to record his killings, and there were allegedly 54 knots at the time of his death.

William T. Anderson was one of the most despicable Confederate guerillas of the American Civil War. Conducting operations against the Union in the middle of the guerilla campaign in Missouri and Kansas, he was a dominant figure in the notorious Lawrence Massacre and the Centralia Massacre, garnering the nickname “Bloody Bill” for the viciousness of his activities. Like fellow Confederate irregulars like William Clarke Quantrill and Jesse James, pieces of Anderson’s life are masked in uncertainty, giving rise to an idealistic guerilla mythology.

Anderson was born in 1840 in Hopkins County, Kentucky, to William C. and Martha Anderson. As a child, his family moved to Huntsville, Missouri, and in 1857 the Andersons moved again to Kansas and settled near Council Grove. Despite not being slave owners, the Andersons were extremely proslavery. In addition to making friends with a local proslavery judge, I.A. Baker, the family personally suffered the effects of the “Bleeding Kansas” conflict over the legality of slavery that had involved the territory.

By 1860, Anderson had become a property owner, entered the freight shipping business with his father, and started horse trading. The outbreak of the Civil War brought on an intensified demand for horses, and Anderson began stealing horses and selling them along the Santa Fe Trail. In late 1861, he and Judge Baker tried to join the Confederate Army, but the 6th Kansas Cavalry in Vernon County, Missouri, attacked them. After being caught, Baker detached himself from the Anderson family, issuing a warrant for the arrest of William’s brother, Griffith. When William sought to have the warrant squashed, a quarrel began in which Baker shot and killed Anderson’s father. On July 2, 1862, William murdered Baker, burned his home, and escaped to Missouri.

In Missouri, William and his brother Jim formed a gang with Bill Reed, robbing and attacking Union soldiers before joining Quantrill’s group in 1863. After a robbery near Council Grove in May 1863, Quantrill’s gang was taken by surprise by federal troops and obliged to split up. Anderson was soon elevated to lieutenant, achieving a quasi-independent command, and took part in raids in Westport, the state of Kansas, and Lafayette County, Missouri.

On the home front, meanwhile, Anderson’s sisters, having functioned as Confederate spies, were detained by Union forces under the command of the reviled Union General Thomas Ewing Jr. After arresting and confining numerous suspected female spies in a makeshift jail in Kansas City, the building collapsed, killing one of Anderson’s sisters among other victims. Confederate sympathizers, including Anderson, believed the collapse was intentional. Anderson’s motivation shifted at that point, as wanton killing became an end. “Bloody Bill” Anderson and his associates went on to earn despicable reputations for torture and mutilation.

Encouraged in part by revenge against General Ewing, Quantrill led approximately 450 Confederate raiders into pro-Union Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21, 1863, killing 190 male civilians and burning and looting most of the town. Anderson and his men allegedly behaved with excessive violence. Union retaliation intensified, most notably by Ewing’s Order No. 11, forcing the abandonment of rural areas in four counties in western Missouri. The order influenced all rural residents regardless of their allegiance. Those who could show their loyalty to the Union were authorized to stay in the involved area but had to depart their farms and move to towns near military outposts – those who could not had to leave the site altogether. Many of Quantrill’s men, including Anderson, headed to Texas. In Texas, hostilities increased between Anderson and Quantrill, resulting in Anderson having his commander arrested for killing a Confederate officer. This break with Quantrill set the stage for the next segment of Anderson’s guerilla mission.

Anderson returned to Missouri in the spring of 1864 and was clear of Quantrill’s control. Anderson’s men concealed themselves as Union soldiers and mounted several attacks in which they ambushed federal soldiers and murdered and scalped civilians. Anderson soon became the most infamous guerilla in Missouri, spreading his local network and drawing other murderous people, including Jesse James, into his orbit.

Anderson conducted a raid near Centralia, Missouri, on September 27, 1864. Having robbed Unionist Congressman James Collins, Anderson had captured a Union passenger train and killed 22 cashiered Union soldiers who had surrendered. Anderson’s men were chased by the 39th Missouri Volunteer (Union) Infantry. After a separate skirmish later in the day, called the Battle of Centralia, Anderson’s men ambushed the outgunned Union pursuers. His men mutilated and brutalized the federal survivors of the battle. The initial murders and the aftermath collectively became known as the Centralia Massacre.

Pursued by Union authorities, Anderson’s escape from Centralia involved the looting and torturing of Union sympathizers and several instances of rape, particularly in an attack on Glasgow, Missouri. Under Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Cox, Union forces finally caught up with Anderson and his approximately 150 men on October 26, 1864. A brief battle ensued in which Anderson was shot in the head and died instantly. Union soldiers photographed Anderson’s body and marched it through the streets of Richmond, Missouri, burying it nearby (it was later reinterred). Cox became a Union hero, and Anderson’s death later motivated Jesse James’s 1869 bank robbery in Gallatin, Missouri, where he erroneously shot someone he assumed was Cox.

Like Quantrill and James, postwar histories cast Anderson as a sadistic murderer or a dashing Confederate hero. Recent historians, however, have stationed Anderson within the world of slavery politics, political violence, and wartime atrocity from which he arose. Most agree that his actions and persona embodied some of the war’s most savage aspects. Heavily mythologized, Anderson has been featured in various popular culture media.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment