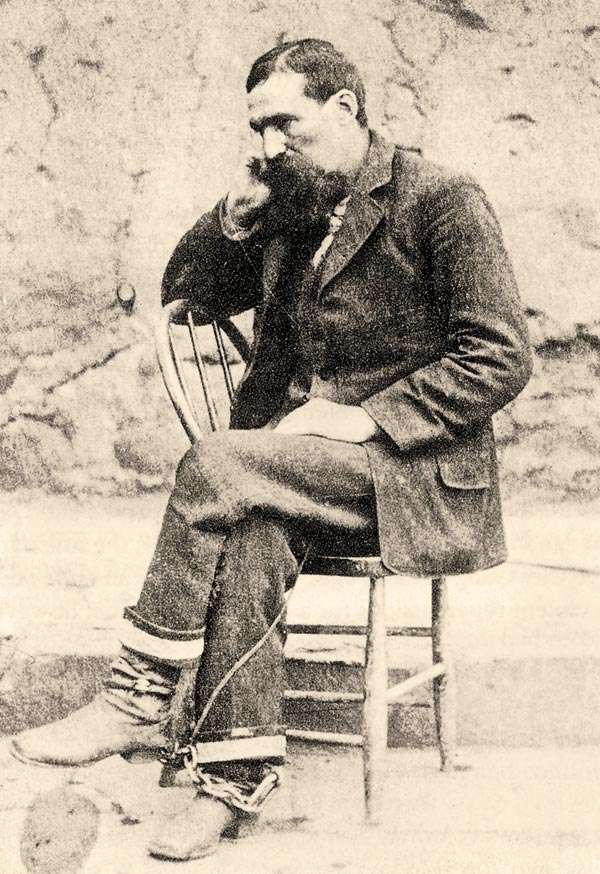

Image: Milt Yarberry shortly before his hanging, while shackled to his chair at the prison in Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory. (Public Domain)

People change their names for many reasons. In the old West, it was just as likely that a person was attempting to run away from something because of something to hide or quite simply a desire not to be found. This was the case of John Armstrong, who in short order would become known as Milt Yarberry, gunslinger.

Armstrong was born and raised in Arkansas. Around 1860, the Armstrongs became involved in a land dispute of some seriousness because John killed a man because of it. The Armstrong family was well thought of, and the incident disgraced the family. For this reason, John Armstrong left home for good, and because he was wanted for murder, he decided to change his name. A few months passed, and John was residing in Helena, Arkansas, when an argument between him and another man resulted in the killing of the other man. We know very little of this second murder. As a result, he ran away again and changed his name.

He began calling himself Milt Yarberry and soon joined up with the outlaws Dirty Dave Rudabaugh and Dave Mather. In 1870, Mather worked as a laborer and lived with a cousin. The pay was minuscule because, between 1870-73, Rudabaugh, Yarberry, and Mather carried out several robberies, mainly in Missouri and Arkansas. When the trio was connected to the murder of a prominent rancher in Sharp County, they split up and went their separate ways. Mather returned to Connecticut and became an able seaman, eventually ending up in New Orleans. Rudabaugh went to South Dakota, where he began robbing stagecoaches. Yarberry settled in Texarkana, on the Arkansas side. When a bounty hunter showed up in town, asking questions about John Armstrong, Yarberry murdered him. A bounty of $200 was offered for the arrest of John Armstrong (a.k.a. Milt Yarberry).

Yarberry bolted to Texas and enlisted in the Frontier Battalion of the Texas Rangers. After joining up, he was assigned to Jack County, and although he only remained with the rangers for a short time, he served with honor and earned a decent reputation for toughness and loyalty.

In 1876, Yarberry was in Decatur, Texas, living under the name John Johnson. Consorting with a man named Bob Jones, he opened a saloon. All might have gone well, but a second bounty hunter had shown up looking for a fellow wanted for murder in Sharp County, Arkansas. Yarberry promptly sold his half of the saloon to Jones and fled town. A few days later, the bounty hunter’s body was found a few miles outside town full of bullet holes.

For the next few years, Yarberry kept moving. In 1877, he was in Dodge City, Kansas, and a year later, in Canon City, Colorado. He partnered with Tony Preston in Colorado, starting a saloon and variety house. Eddie Foy performed at the variety house. In an interview many years later, Foy said that Yarberry was an excellent violinist but often remiss in paying his debts. When Eddie Foy and Jim Thompson had completed their engagement, which had lasted several weeks, Yarberry and Preston could not settle the account. This prompted Thompson to steal a barrel of whiskey and consider the matter ended. What surprised Foy the most was that Thompson had the guts to go up against Milt Yarberry.

On March 6, 1879, because of some disagreement between Tony Preston and a local bartender, a man employed at two saloons, the bartender entered Preston’s bar and shot him. Preston was seriously wounded, and Yarberry joined the posse to pursue the shooter. The man eluded them but turned himself into the town marshal the next day. He stated that he only escaped because he was terrified of being lynched.

When Preston was well enough to travel in May, he and his wife Sadie packed up and moved to San Marcial, New Mexico. Some have suggested that Yarberry’s saloon was a brothel, which is certainly plausible given the reputation of Las Vegas at that time.

Eventually, Yarberry sold his piece of the business and ventured to San Marcial, New Mexico, where he rejoined Tony Preston. Preston was still recovering from his wounds. Yarberry left San Marcial within a month with Sadie Preston and her four-year-old daughter.

Yarberry and Sadie wound up in Albuquerque, where Milt made friends with county sheriff Perfecto Armijo. With Armijo’s help, Yarberry became Town Marshal, the city’s first lawman. He was needed because, in 1880, Albuquerque was rife with gun violence. Within a short time, Yarberry confronted two separate gunmen, and as both men opposed arrest, Yarberry ended up killing them both.

In January 1881, a man named Harry Brown arrived in town. He was a self-proclaimed gunman without common sense or fear. In 1876, Brown had taken part in stopping an attempted robbery by Dave Rudabaugh and others near Kinsley, Kansas. While he was never known to have shot anyone, he boasted about killing numerous men. This was typical of drifters in the Old West, especially among those with drinking problems. His drinking diminished his temper, and he was known for pulling his gun with little incitement.

Brown and Sadie became familiar with each other under unknown circumstances, but the two became romantically involved by February. On March 27, Brown and Sadie enjoyed dinner at Gerard’s Restaurant. Up until this day, Yarberry was unaware that the two were involved. Sadie left her daughter at home in Milt’s care while she went out on the town with Brown. John Clark, a coach driver, had taken the couple to the restaurant and was the only eyewitness to what occurred.

Brown and Sadie went into the restaurant and were seated. Shortly after, Yarberry came strolling up the street holding the hand of Sadie’s daughter. Someone told Brown that Yarberry was coming down the road, so Brown walked out the restaurant doorway. Yarberry walked past Brown with the little girl in hand, took her to her mother, and then a moment later, walked back outside. He spoke a few words to Brown, and the man became angry.

Brown escorted Yarberry to a nearby vacant lot, still speaking in elevated tones, Brown exclaiming that he was unafraid of Yarberry. Prior to reaching the vacant property, Sadie appeared in the doorway of the restaurant and called out to Brown. Brown immediately struck Yarberry in the face while pulling out his weapon and firing. The bullet grazed Yarberry’s hand. Yarberry then drew his gun and shot Brown twice in the chest, thus ending Brown’s life.

Sheriff Armijo took Yarberry into custody and detained him until an inquest was held. Numerous witnesses testified that they heard Brown say on more than one occasion that he planned to kill Yarberry, while others swore that Brown had drawn his weapon first. The inquest cleared Yarberry based on self-defense, but some citizens complained that he had received preferential treatment and demanded a grand jury be held to hear the evidence. A grand jury convened in May 1881. Yarberry’s attorney, S. M. Barnes, paraded several witnesses on Yarberry’s behalf, and the charge of murder was subsequently dismissed.

On June 18, 1881, Yarberry rested on his friend Elwood Maden’s porch, conversing with gambler Monte Frank Boyd. As they were chatting, a gunshot could be heard coming from the direction of the Greenleaf Restaurant. Yarberry and Boyd immediately went to see what was happening. The next few moments were chaotic, and witness accounts varied widely. Yarberry asked a bystander if he knew who had fired the shot. The person pointed toward a man walking away from the restaurant, and Yarberry called out to him to stop; Yarberry wanted to speak with him. Three shots were fired within mere seconds, and Charles D. Campbell was dead on the street.

Sheriff Armijo arrested both Yarberry and Boyd. Yarberry claimed that Campbell, whom he did not know, had turned toward him and began shooting, so he fired back in self-defense. One of Campbell’s bullet wounds was in his back, but Yarberry clarified that it most likely happened when having been shot, Campbell’s body spun around after being shot in the chest. Nobody could corroborate Yarberry’s story that when Campbell turned around, his gun had already drawn. Once again, Yarberry and Boyd were cleared of all wrongdoing at an inquest about the shooting.

Once again, a number of citizens protested that Yarberry was being “let off.” Boyd left Albuquerque and headed west toward Arizona. Yarberry was again taken into custody and held for trial. A grand jury indicted him in the murder of Campbell. New Mexico’s governor, Lionel Sheldon, having only recently been voted into office, was of a mind to end the needless killing in New Mexico. This was the time of the Lincoln County War, and a man named William F. Bonney was running loose in the state. Governor Sheldon decided to make an example of Yarberry. The territorial attorney general, William Breedon, prosecuted the case. Yarberry was represented by lawyers Jose Francisco Chavez and John H. Knaebel. During the trial, Thomas A. Parks, an attorney from Platt City, Nebraska, testified that he witnessed the entire event. He saw no gun in Campbell’s hand. It was damning testimony, to be sure.

In his defense, Yarberry maintained that Campbell’s gun had indeed been fired and that Campbell had shot at him at least once. No one could testify for Yarberry, but no one, except for Parks, could repudiate his testimony. Yarberry also testified that he had fired only once, hitting Campbell in the chest, adding that he had only shot Campbell because the man had fired at him first.

The trial lasted three days. Yarberry was convicted of murder and was sentenced to hang. While awaiting execution, on September 9, 1882, Yarberry and three other men escaped from the Santa Fe jail. New Mexico authorities put a $500 bounty for his recapture. The other escapees were quickly apprehended, but Yarberry managed to elude authorities. Santa Fe County Sheriff Romulo Martinez organized a posse, and they promptly began searching for him. On September 12, Santa Fe Police Chief Frank Chavez captured Yarberry twenty-eight miles outside town limits.

In February 1883, Yarberry’s repeated appeals to the federal government were denied. Despite their insistence that their client was innocent, Yarberry’s lawyers’ attempts proved fruitless. In his final interview, a journalist observed that he looked pale, to which Milt Yarberry stated, “Maybe. But I ain’t sick, and I ain’t scared, neither.”

On February 9, under guard by the so-called Governor’s Rifles, Yarberry was taken to the gallows. His friend, Sheriff Armijo, was tasked with pulling the lever to the trap door, through which Milt Yarberry/John Armstrong would fall. Over 1,500 people attended Yarberry’s hanging. His last words were, “Gentlemen, you are hanging an innocent man.”

Long after Yarberry’s death, his supporters, which included Sheriff Armijo, continued to insist on his innocence. According to Armijo, the issue wasn’t guilt or innocence. The problem was that the wealthier community members wanted him dead because he hurt the town’s reputation simply because he had been involved in many shootings. Sheriff Armijo maintained that whether he was innocent or not mattered little as the more affluent people of the town were more concerned with the town’s image.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment