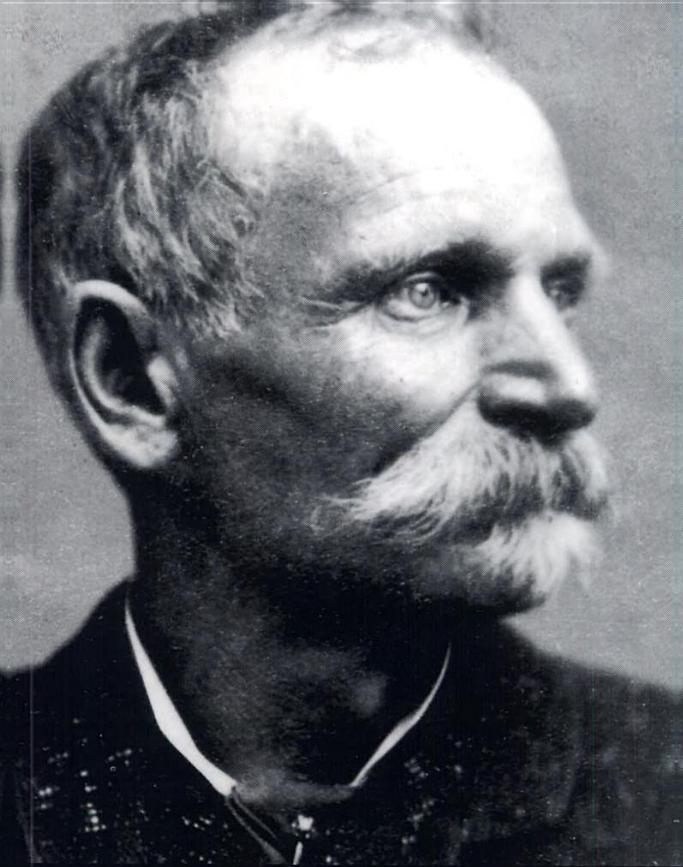

Image: Charles Bowles, aka “Black Bart”, American stagecoach robber. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, November 3, 1883, the driver of a stagecoach almost catches the outlaw who has robbed him in northern California. Charles “Black Bart” Boles managed to escape rapidly but left behind an incriminating item that would ultimately send him to prison – a handkerchief with a laundry mark.

Charles “Black Bart” Boles was born in New York around 1830. In his younger days, he deserted his family for the gold fields of California, but he failed to become rich and instead became a criminal.

By the mid-1850s, stagecoaches owned by Wells Fargo transported the gold from California. Often traveling through remote regions, the Wells Fargo stagecoaches quickly became prime targets for outlaws; over 15 years, the company was robbed of over $415,000 in gold.

Boles committed his first stagecoach robbery in July 1875. Sporting a flour sack over his head and a black derby hat, he stopped a stagecoach near the California town of Copperopolis. When guards saw what they thought were gun barrels sticking out of adjacent bushes, they gave the strong box to Boles. He opened it with an axe and fled with the gold, though his “gang” of concealed gunmen stayed behind. When the guards returned to retrieve the box, they realized the “rifle barrels” were just sticks fastened to branches.

Buoyed by this triumph, Black Bart started a sequence of stagecoach robberies. During his criminal career, he never shot anybody nor stole from a single stage passenger; he gained fame for the short poems he left behind, signed by “Black Bart, the Po-8.” Wells Fargo, however, was not pleased – the company directed its private police force to catch the outlaw, dead or alive.

Detective James Hume began looking for clues about where the robberies took place. Black Bart always used the same method and disguise, and all the robberies were committed in northern California.

By late 1882, Hume finally put together a detailed but surprising picture of Black Bart and how he carried out his work. Stage robbery was usually a young man’s game, but to the 55-year-old’s amazement, Bart was a man nearer to his age, maybe older. People around the robberies remember seeing a gray-haired and mustachioed man they thought was a migrant farm laborer. He always wore a derby, carried a bundle wrapped in a blanket, had boots slit open at the sides to relieve pressure on his corns, and was seen walking quickly. If this man were the one Hume wanted, he would be an impressive walker, having once robbed two different stagecoaches thirty miles apart in 24 hours.

Within months Bart struck again on the same steep hill where his first stick-up happened. But this time, he was forced to escape. Driving up the hill, the coach was halted by the man in the sack mask. Calling out, “Throw down the box,” and taking out his axe, the thief was ready to open the strong box when the driver’s associate came out of the underbrush with his gun and fired. The driver and his associate looked for the robber’s dead body, only to find nothing. They were baffled. It would still be several weeks before the criminal would be arrested.

In the 50 months he was incarcerated in San Quentin prison, Charles Boles had much time to consider how he had been apprehended. And in mulling it over, his final escape must have brought him some fulfillment. Even though the driver had looked a long while for his body, they found only a derby, a straight razor, binoculars, and some buckshot wrapped in a handkerchief. Bart’s wound had been minor, allowing him to keep running faster than was normal for a man his age.

During his criminal career, Boles gathered a mere $18,000 from Wells Fargo. But in 1883, that was a substantial amount that could keep him in the refined style he favored. He presented himself as Charles Bolton, a prosperous mining man; who lived in affluent San Francisco hotel suites; often traveled to Southern California for amusement; wore beautiful clothing, and loved poetry. However, the Southern California trips were often a deception, opportunities for Boles to practice the only trade he had ever known.

One day in 1883, sporting a new derby hat, diamond stickpin, diamond ring, and a gold watch, Boles twirled his walking stick and stepped out the door of San Francisco’s Webb House hotel into the waiting arms of his laundryman. This was a bad sign.

Near the hotel’s laundryman were Detectives Hume and Morse of Wells Fargo & Co., who wanted to meet the aging dandy Charles Bolton. So did their superiors. For weeks they had visited every wash house in northern California trying to identify the handkerchief with the laundry mark F.X.O.7. It had been tied around some buckshot at the scene of Black Bart’s last hold-up of a Wells Fargo stagecoach near Copperopolis, California.

Detectives Hume and Morse were not astonished when Boles first rejected that he had any correlation with the stagecoach thefts, stating warily, “I am a gentleman.” Morse confessed that Boles “looked anything but a robber.” More interrogation, however, brought about an admission of guilt and Boles’ factual background as a Midwesterner, a Civil War veteran, and a man who deserted his wife and children to come west and seek a fortune. But they were shocked by what he had to relate about the buckshot wrapped in the laundry-marked linen. Black Bart had never loaded his shotgun in eight years of stagecoach robberies.

He had lived fine during his robbery career; Boles had saved much of his proceeds and returned it to Wells Fargo when he was incarcerated. This, and the reality that he had never hurt anyone during a robbery, allowed him to plead guilty to one count of armed robbery and receive a six-year sentence in the state prison.

Regarding his age – somewhere around 60 – Boles was freed from prison in 1887 before finishing his sentence. His reputation had grown in the four years and sixty days of his imprisonment, and he left San Quentin more renowned than when he first went in. Boles would die in 1917 at age 88.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment