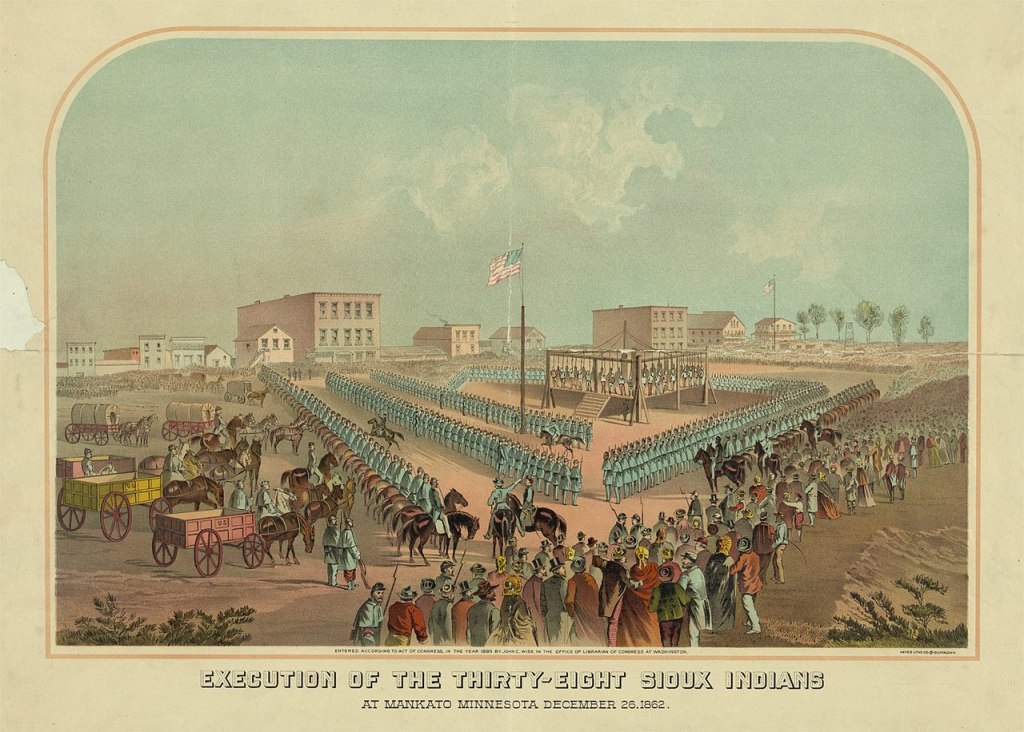

Image: Execution of the thirty-eight Sioux Indians at Mankato Minnesota, December 25, 1862. President Abraham Lincoln ordered the mass execution of 38 Native Americans in Minnesota for revolt against the government in 1862. (Public Domain).

On this day in history, November 5, 1862, 303 Santee Sioux are found guilty of raping and murdering American pioneers and are condemned to hang in Minnesota. A month later, President Abraham Lincoln exchanged all but 39 death sentences for life in prison. One of the Sioux Indians was granted a last-minute stay of execution. Still, the other 38 were executed together on December 26, 1862, in a mass event watched by a large crowd of 2000 Minnesotans.

The Santee Sioux were found guilty of entering the supposed “Minnesota Uprising,” which was part of the more significant Indian wars throughout the American West during the last half of the nineteenth century. American settlers occupied the Santee Sioux territory in the Minnesota Valley for nearly fifty years. Federal government pressure gradually pushed the Native populations to move to smaller reserves along the Minnesota River.

At the reservations, the Santee were horribly abused by immoral federal Indian agents and workers; during July 1862, the agents pushed the Native Americans to starvation by refusing to dispense food stores since they had not yet been paid their usual bribes. The workers coldheartedly disregarded the Santee’s request for assistance.

Furious and at the boundaries of their patience, the Santee fought back, killing American settlers and taking women as captives. The opening attempts of the U.S. Army to end the Santee warriors were unsuccessful. In a battle at Birch Coulee, the Santee Sioux killed 13 American soldiers and wounded another 47 troops. Yet, on September 23, a force under General Henry Sibley defeated a large group of Santee warriors at Wood Lake, regaining many detainees and compelling many Sioux to capitulate.

The trials were flawed in many ways, even by military standards, and the officers who administered them did not perform them according to martial law. The 400-plus trials started on September 28, 1862, and were finished on November 3, some lasting less than 5 minutes. No explanations of the proceedings were given to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by defense lawyers.

The Santee Sioux were not prosecuted in a state or federal criminal court but before a military commission comprised totally of Minnesota settlers. They were condemned, not for the offense of murder, but for killings executed during the war. The executive review was performed not by an appellate court but by the President of the United States. Many battles happened between Americans and the Indian nations, but in no other war did the United States apply criminal penalties to punish those beaten in those conflicts.

The trials were also administered in a mood of excessive racist enmity towards the perpetrators articulated by the community, the elected representatives of the state of Minnesota, and the men directing the hearings themselves. By November 3, the military commission had conducted trials of 392 Sioux men, with as many as 42 trials held in one day. Not unexpectedly, given the socially volatile environment under which the trials occurred, by November 7, the verdicts were ready. The military commission declared that 303 Sioux prisoners had been found guilty of murder and rape and were condemned to death.

Major General John Pope notified President Lincoln of the sentences on November 10, 1862. He replied, “Please forward, as soon as possible, the complete record of these convictions. And if the record does not indicate the more guilty and influential of the culprits, please have a detailed statement made on these points forwarded to me. Please send all by mail.”

When the death penalties were widely known, Henry Whipple, the Episcopal bishop of Minnesota and a reformer of American Indian policy, published an open letter. He also traveled to Washington, D.C., in the fall of 1862 to encourage Lincoln to be lenient. Conversely, General Pope and Minnesota Senator Morton Wilkinson cautioned Lincoln that the white population was against leniency. Governor Ramsey told Lincoln that unless all 303 Sioux were executed, Minnesotans would take matters into their own hands.

Lincoln reviewed the transcripts of the 303 trials with the aid of two White House lawyers in about one month. On December 11, 1862, he spoke to the Senate concerning his final verdict. Ultimately, Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 264 Sioux prisoners and allowed the execution of 39 men. Yet, on December 23, Lincoln canceled the execution order of one man after General Sibley sent new information that led him to question the prisoner’s guilt. Therefore, the number of sentenced men was lowered to 38.

Even partial leniency caused protests from Minnesota until the Secretary of the Interior gave white Minnesotans “reasonable compensation for the depredations committed.” Republicans lost seats in the 1864 election. Ramsey (by that point, a Senator) told Lincoln that more hangings would have caused a more significant electoral majority. The President allegedly responded, “I could not afford to hang men for votes.”

A 2,000-man military guard was deployed for the hanging of the 38 prisoners on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota. It is the largest single-day mass execution in American history. The size of the guard force was required because of the large numbers of angry Minnesotans positioned at Mankato and the fear of what they would do to the prisoners not being hanged.

The execution was a public affair. The gallows were constructed around the outside of the town square with ten nooses per side. After the regimental surgeons declared the men dead, they were buried en masse in a sand bar in the Minnesota River. Before they were buried, a person called “Dr. Sheardown” removed some dead prisoners’ skin. Despite a large guard force situated at the gravesite, all the bodies were disinterred and taken away the first night.

The ensuing trials of the convicts paid little consideration to the travesties the Santee Sioux had endured on the reservations and fundamentally served to feed the overwhelming yearning for retribution. However, President Lincoln’s commutation of most of the death sentences displayed his insight that the Minnesota Uprising had been deep-rooted in a long series of American cruelties toward the Santee Sioux.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment