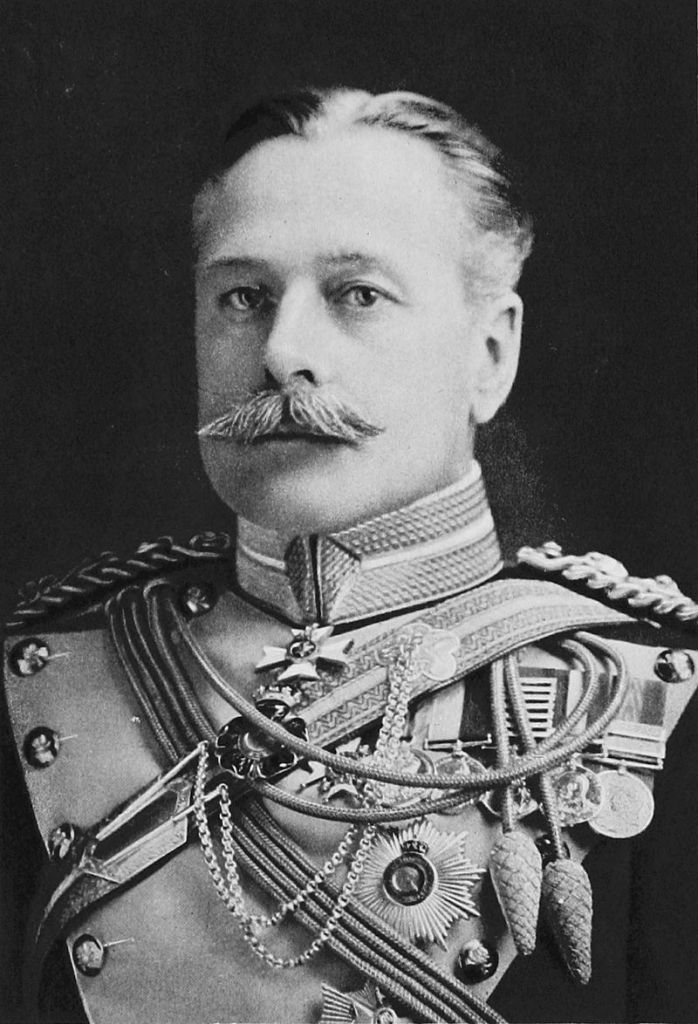

Image: Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, 1917. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, November 18, 1916, British Commander in Chief Sir Douglas Haig ended his army’s offensive near the Somme River in northwest France, ending the larger-than-life Battle of the Somme after more than four months of blood-stained battle.

The Battle of the Somme, which occurred from July to November 1916, started as an Allied offensive against the German army along the Western Front of World War I, close to the Somme River in France. The battle became one of the most unpleasant, deadly, and costly battles in human history, as British forces endured more than 57,000 casualties – including over 19,000 troops killed – solely on the first day of the battle. By the last day of the Battle of the Somme, more than 3 million soldiers from both sides had clashed by mid-November, and more than 1 million had been wounded or killed.

Preceding the attack, the Allies initiated a week-long heavy artillery barrage, using 1.75 million shells to destroy the barbed wire guarding German trench defenses and ruin the German positions.

On the morning of July 1, 1916, 11 divisions of the British 4th Army – many volunteer soldiers heading into battle for their first time – began moving forward on a 15-mile front north of the Somme River. Simultaneously, five French divisions proceeded on a ten-mile front to the south, where German defenses were more vulnerable.

Allied leaders were confident the barrage would break German defenses enough for their soldiers to advance. But the barbed wire remained unbroken in numerous areas, and the German positions, many of which were far underground, were more challenging than expected.

Along the line, German machine gun fire killed thousands of the attacking British soldiers, many of whom were stuck in “no man’s land” between opposite sides. Over 19,000 British soldiers were killed and more than 38,000 wounded before the first day was over – nearly as many casualties as British forces endured when the Allie lost the Battle of France during World War II (May-June 1940).

Other British and French armies had more accomplishments in the south, though these gains were restrained contrasted to the shocking failures suffered on that first day of battle.

Nevertheless, British Field Marshal Douglas Haig was resolute about pressing on with the offensive. Over the next few weeks, the British launched a series of minor assaults on the German line, increasing pressure on the Germans and forcing them to move weapons and soldiers from the Battle of Verdun.

Early on July 15, British soldiers launched another artillery bombardment, followed by a significant attack on the Bazentin Ridge in the northern part of the Somme. The attack surprised the Germans, and the British managed to move forward 6,000 yards into enemy territory, capturing the village of Longueval.

But every small amount of progress came at the expense of heavy casualties in this long and deadly war of attrition. The Germans garnered 160,000 casualties, and the British and French more than 200,000 wounded and killed by the end of July.

By the end of August 1916, with German morale low due to lost ground at the Somme and Verdun, Germany’s General Erich von Falkenhayn was substituted by Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. The command change indicated a shift in German tactics: They would create a new defensive line behind the Somme front, giving up land but letting them inflict even more losses on the forward-moving Allied forces.

On September 15, while striking Flers Courcelette, the British artillery bombardment resulted in the advance of 12 divisions of troops and 48 Mark I tanks, appearing for the first time on a battlefield. But the tanks were still in the developmental phase, and several failed before reaching the front line. Though the British could only move forward 1.5 miles, they took over 29,000 casualties and fell short of their objective.

At the beginning of October, poor weather hindered another Allied assault, with soldiers straining to move across muddy territory while enduring withering fire from German fighter planes and artillery. The Allies made their last onslaught of the battle in mid-November 1916, striking the German locations in the Ancre River valley.

With the onset of winter, Haig ultimately called an end to the offensive on November 18, terminating the blood-stained battle of attrition on the Somme, at a minimum, until the next year. Over 141 days, the British had progressed just seven miles and could not crack the German line.

For the most part, the Battle of the Somme, particularly the dreadful first day, will be remembered as the embodiment of the vicious and ostensibly meaningless slaughter that illustrated trench warfare during World War I. British officers, especially Haig, would be condemned for remaining vigilant and continuing the offensive despite such tremendous casualties.

Countless British soldiers who battled at the Somme had volunteered for the army in 1914 and 1915 and witnessed combat for the first time at the Somme. Many were part of Pals battalions or units made up of friends, neighbors, and relatives in the same community.

In one touching example of a community’s loss, 725 men from the 11th East Lancashire battalion (known as Accrington Pals) went into battle at the Somme on July 1; 584 were wounded or killed.

Despite its overwhelming costs, the Allied victory at the Somme wreaked significant harm on German positions in France, driving the Germans to withdraw to the Hindenburg Line in March 1917 deliberately rather than continue to fight over the same land that spring.

Though an accurate number is unclear, German losses by the finale of the Battle of the Somme undoubtedly surpassed Britain’s, with some 450,000 soldiers dead and wounded compared with 420,000 British soldiers. The remaining British armed forces also acquired beneficial experience, enabling them to achieve final victory on the Western Front.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment