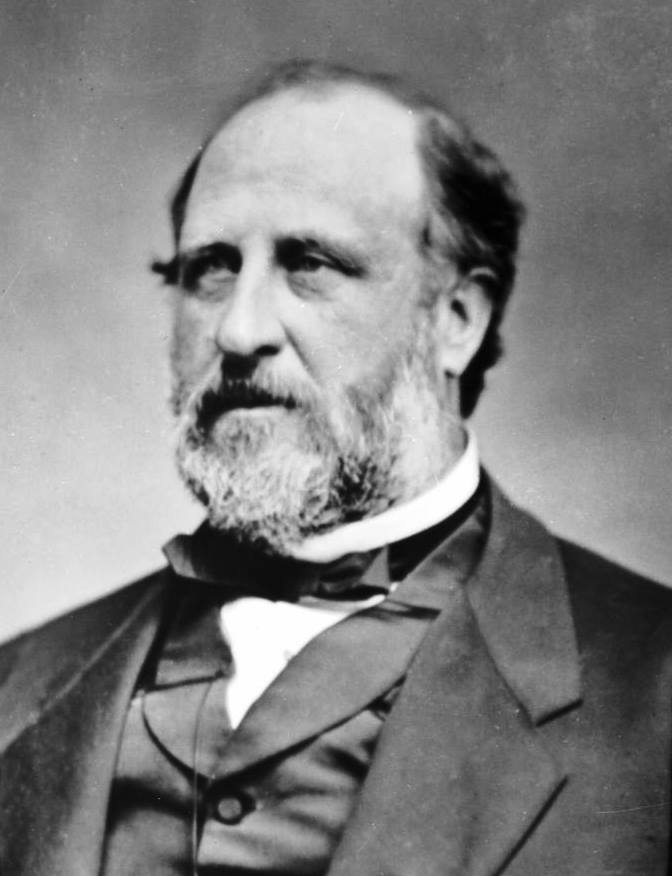

Image: William Magear “Boss” Tweed, 1870. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, November 19, 1873, William Magear “Boss” Tweed, leader of New York City’s crooked Tammany Hall political organization during the 1860s and 1870s, is convicted of defrauding New York City of $6 million and was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment. Thomas Nast, a political cartoonist, happily – and courageously – ridiculed the Tammany Hall boss in multiple cartoons, encouraging newspapers and authorities to investigate the criminal activities of “Boss” Tweed.

Tweed became a formidable person in Tammany Hall – New York City’s Democratic political machine – in the late 1850s. By the mid-1860s, he had taken the top job in the organization. He created the “Tweed Ring,” which freely bought votes, inspired legal corruption, extricated millions from city contracts, and controlled New York City politics. The Tweed Ring reached its pinnacle of duplicity in 1871 by remodeling the City Court House, which cost nearly $15 million to build, including $9 million in kickbacks to Tweed and his cronies.

The courthouse, a blatant abuse of city funds, was uncovered by The New York Times. Tweed and his lackeys hoped the condemnation would die down. Still, thanks to the labors of adversaries such as Harper’s Weekly political cartoonist Thomas Nast, who operated a crusade against Tweed, almost every Tammany Hall member was driven from office in the elections of November 1871.

Tweed kept power by using “patronage” – giving great city jobs to devoted supporters (as Commissioner of Public Works, Tweed hired 12 “manure inspectors”) – and by providing substantial support to Irish Catholic immigrants, who paid him back with loyalty at the ballot box.

Boss Tweed functioned with impunity until he began to annoy a 30-year-old political cartoonist, Thomas Nast. Nast initiated an unrelenting anti-corruption crusade against Tweed in Harper’s Weekly. In his vicious and hilarious caricatures, he made Boss Tweed out to be a larger-than-life criminal and Tammany Hall a den of thieves.

Boss Tweed was ultimately brought to justice primarily due to Nast’s pitiless cartoons and determined reporting from a new newspaper called The New York Times.

Thomas Nast and his family were originally from Germany, and in 1846 they moved to New York City. During that time, William Tweed was even now a minor hero in New York City as the leader of Americus Fire Company No. 6, one of many volunteer firefighting companies in Manhattan that were no more than street gangs with fire hoses.

During the American Civil War, Nast allied himself with the Republicans and put his artistic talents to work for the abolitionist cause and the Union. When things looked bleak for Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 election, Nast published a two-page drawing called “Compromise with the South” that helped save the struggling president of the United States. In the election of 1868, Ulysses S. Grant stated that his win was due to “the sword of Sheridan and the pencil of Nast.”

By the late 1860s, Nast was a productive and significant contributor to Harper’s Weekly, the most famous illustrated newspaper. That’s when Nast began to turn his attention to Tweed and his Democratic Tammany Hall political machine.

Nast saw things his whole life as a black-and-white view of what was right and wrong. If someone was corrupt, Nast was happy to go after anyone who fits into that category. With Boss Tweed, Nast saw a chance to go after something that would make him famous.

In the 1870s, weekly magazines and newspapers like Harper’s Weekly were mainstays in the neighborhood taverns where working-class New Yorkers gathered to socialize and even vote in local elections. Somebody at the bar would read the articles out loud for those who could not read. Political cartoons, including Nast’s vicious swipes at Tweed, were put on the walls for everyone to view.

Nast drew ideas for his cartoons from articles and editorials about Tweed’s brash corruption in The New York Times. The more the Times exposed, the more enraged and courageous Nast’s illustrations became. A cartoon titled “The Brains” featured an obese Tweed with a bag of cash for a head. A different one showed all of New York under the gigantic thumb of Tweed.

The damaging capabilities of Nast’s cartoons were top of mind for Tweed.

“Let’s stop those damned pictures,” Tweed allegedly stated. “I don’t care so much what the papers write about me – my constituents can’t read, but damn it, they can see pictures.”

In 1873, Nast was residing in Harlem with his family when a stranger (who turned out to be Tweed’s lawyer) knocked at their door, offering a bribe of $500,000 for him to go on an extended vacation to Europe. He turned the offer down and was told: “You’ll be sorry.” Nast took this threat seriously because he promptly moved his family to Morristown, New Jersey.

From the security of Morristown, Nast kept up his persistent campaign against Tweed. He put five or six cartoons out per week for Harper’s.

At his pinnacle, Boss Tweed possessed tremendous riches and influence. He owned an estate in Greenwich, Connecticut, a 5th Avenue mansion, and two steam-powered yachts. Added to his job as the Commissioner of Public Works, Tweed was the director of several companies.

Then The New York Times finally took possession of a “smoking gun,” a secret Tammany Hall ledger describing how Tweed and his “Ring” stole a fortune from the city. When investigators revealed the complete range of Tweed’s crimes, the total theft came to $50 million (nearly $1 billion today).

In the end, editors and reporters at The New York Times were the downfall of Tweed, but Nast’s steady stream of negative political cartoons had a considerable effect on the fight against Tweed. From the ordinary person’s view on the street, Nast brought down Tweed.

Tweed was found guilty of corruption in 1873 and died in prison in 1877 (after a failed escape attempt to Spain).

Nast, already familiar to the Republican party faithful, became a national celebrity after the Tweed battle. He went on an American tour doing “chalk talks,” where audiences would pay handsomely to view his drawing.

Today, Nast is well known as the cartoonist who produced the donkey and the elephant as the mascots for the Democratic and Republican parties and drew several of the earliest and most iconic images of Santa Claus.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates on new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Donations – History Daily With Francis Chappell Black (history-daily-with-francis-chappell-black.com)

History Daily: 365 Fascinating Happenings Volume 1 and Volume 2 are for sale now from my publisher’s site:

https://yesterdaytodaybooks.etsy.com

Order your copy today to support our efforts.

Thank you.

Francis

Leave a comment