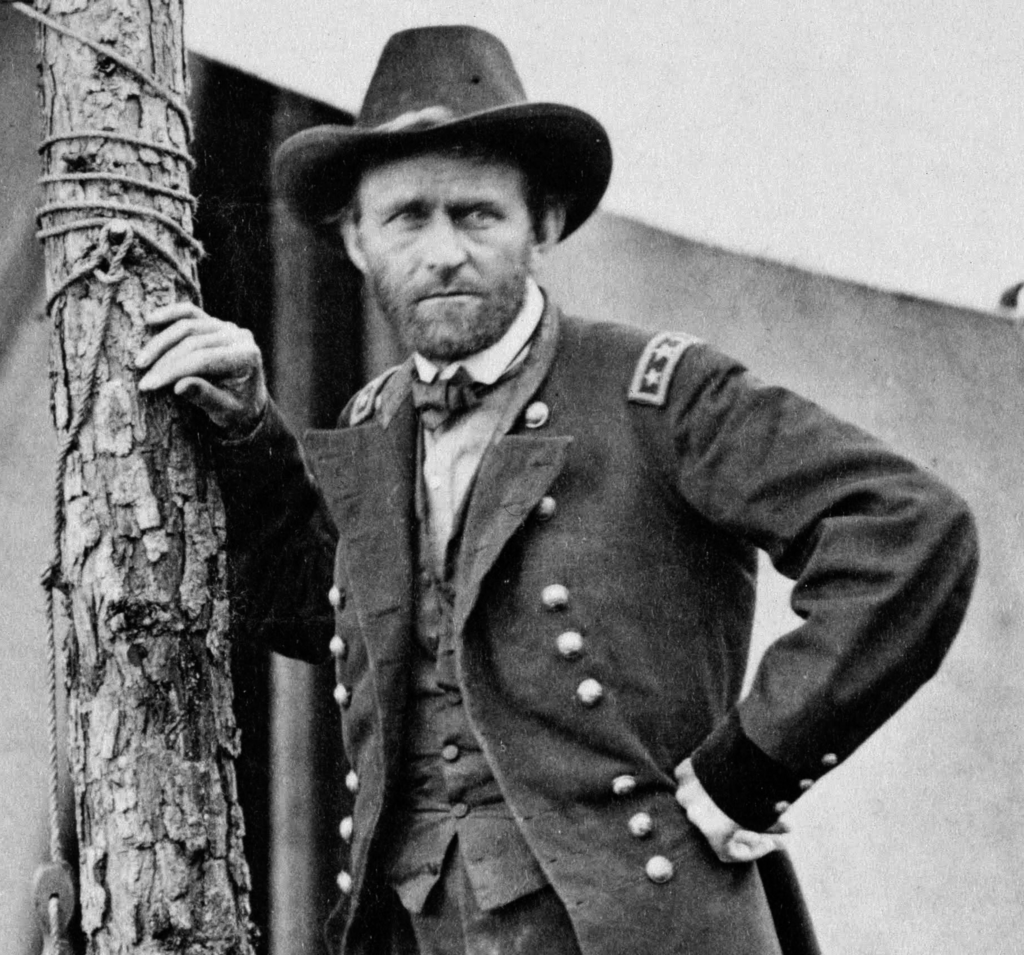

Image: General Grant at his headquarters in Cold Harbor, Virginia, June 1864. (Public Domain).

On this day in history, December 17, 1862, Union General Ulysses S. Grant took aim at Jewish cotton speculators, who he thought were the prime motivators behind the black market for cotton. Grant issued an order banishing all Jewish people from his military district, which included portions of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Kentucky.

At that juncture, Grant attempted to acquire Vicksburg, Mississippi, the last major Confederate refuge on the Mississippi River. Grant’s army had essentially controlled most of western Tennessee, northern Mississippi, and parts of Kentucky and Arkansas. Grant had to engage with several speculators who trailed his army for cotton. Cotton supplies were very short in the North, and these speculators could buy bales in the captured territories and sell them rapidly for a significant return. In December 1862, Grant’s father and friends from Ohio visited him. Grant soon realized that the friends, who were Jewish, were speculators hoping to secure access to captured cotton. Grant was angry and quickly wrote his infamous Order No. 11: “The Jews, as a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders, are hereby expelled from the department within twenty-four hours from receipt of this order.”

Though the 1862 orders were targeted at cotton speculators, they gave all Jews – speculators or not – a mere 24 hours to leave their homes, businesses, and essentially their lives behind. It was the climax of a wave of anti-Semitism sweeping the United States since the late 1850s. This would be a decision that would plague Grant for the rest of his life.

By 1860 there were over 200,000 Jewish people in America, up from 15,000 in 1840. That rise was because of the discrimination and poverty in Germany and Central Europe, where Jewish people were often barred from trade, stopped from marrying, and subjected to pogroms and other aggression.

America offered the promise of economic and social freedom. In the North, Jewish immigrants were only sometimes embraced in their new neighborhoods. New Jewish districts in American cities were often perceived with apprehension by those in the greater community who were unfamiliar with their customs. Once the Civil War started, things got even more dreadful.

In the North, the press criticized Jews for being secessionists and rebels and condemned them for devastating the national credit. Even though there were Jews who filled high-ranking roles within the Confederacy, anti-Semitism was also prevalent in the South.

As soon as the war commenced, illegal trade and trafficking between the North and the South began. Though the Union blockaded Southern ports, supplies still managed to make their way over the border, and racketeers continued their business illegally, notably as the price of cotton rose due to the prohibition. Not only did illegal trading break Union laws, but it compromised the war effort itself.

When cotton arrived from Confederate territory, there was always the risk that it would be paid for in supplies and weapons. The black market was far and wide, disturbing Northern and Southern governments. And the perfect scapegoat were the Jews, who had been typecast in the press as greedy and corrupt.

General Grant, one of the Union Army’s highest-ranking officials, was enraged by the cotton trafficking that harmed the Union’s capacity to damage the South economically. In his mind, the offenders were all Jews. This wasn’t proven by evidence – though Jewish people were active sellers, merchants, and traders, and some most certainly made earnings speculating on cotton, they did not make up most of the black marketeers operating in the field.

In August 1862, as Grant was preparing the Union Army to take Vicksburg, he ordered his soldiers to inspect the baggage of all speculators, giving “special attention” to Jews. In November, he instructed his officers to deny permits to any Jews to travel south of Jackson, Mississippi.

For Grant, discrimination against Jews was interspersed with personal hatred. He started his suppression after learning about a Jewish family’s connection in a ruse to facilitate using his father’s identity to get a legal cotton trading license in Cincinnati.

On December 17, 1862, Grant progressed even further. He dispensed an official order banishing Jews from the Department of the Tennessee, an enormous administrative section under his control that contained areas of Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky. He called the Jews “a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department and also department orders” and gave them 24 hours to leave the area.

The order targeted Jews as a group based on their religion. Although Confederate raids hampered the dissemination of the news of the order and were not well-enforced, it slowly filtered out to Jews in and beyond the concerned area.

News of the order appalled Jewish Americans.

As they prepared to leave their homes and board a river boat away from places like Paducah, Kentucky, Cesar Kaskel and others telegraphed President Lincoln in a desperate bid to broadcast the news of Grant’s bigoted activities. After their forced departure, Kaskel traveled to Washington to oppose the order in person. He contacted Congressman John Gurley of Ohio, who agreed to escort him to the White House.

Lincoln had not heard about Grant’s choice to exile Jewish people from the Department of the Tennessee beforehand. He was extremely shocked by the order and asked his staff for verification. Once they verified that it was genuine, Lincoln rescinded the order.

News of the order continued spreading, and while some editorials agreed with Grant, many denounced its targeting of Jews. Many newspaper editorials applied anti-Semitic tropes about Jews, comparing them to Shylocks and complaining about the destructive power of rich Jews. Grant’s order stirred up an ugly undertone of American life that separated and harmed Jews who came to America for equality.

The bigoted order was quickly suppressed, but the general never forgot it. He spent a lifetime trying to apologize for it. When he ran for president in 1868, he admitted that the order “was issued and sent without reflection and without thinking.” In office, he named more Jews to public office than ever before. He elevated the human rights of Jewish people abroad, opposing pogroms in Romania and directing a Jewish diplomat to object.

But though Grant did the best he could to compensate for his prejudiced order, he undoubtedly helped to increase the anti-Semitism of the 19th century.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black’s” Blog to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment