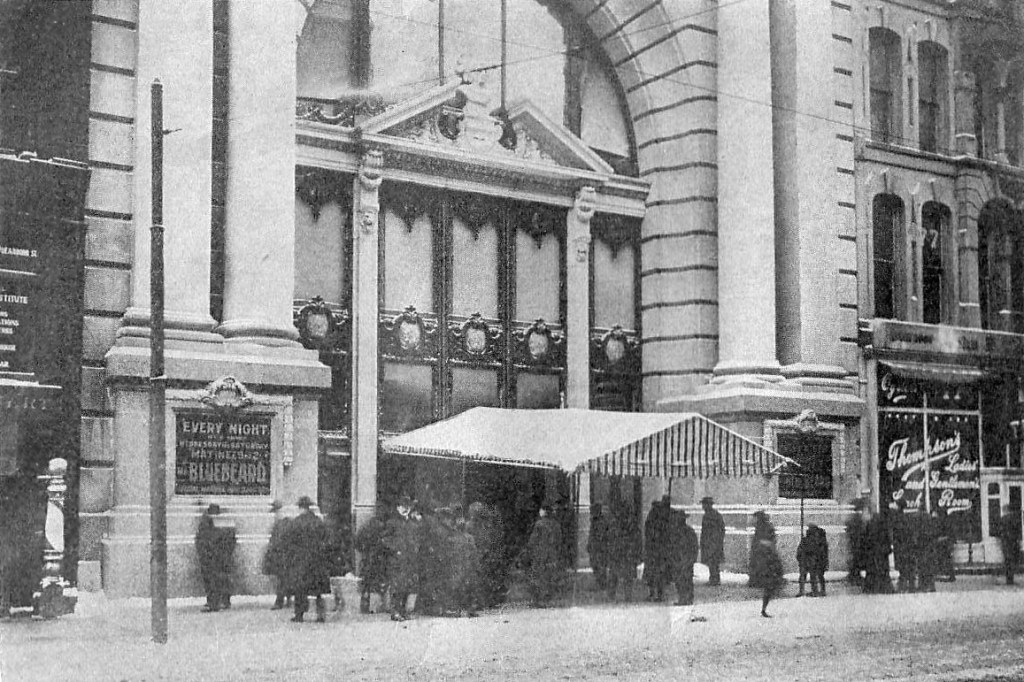

Image: Iroquois Theatre in a 1903 photo. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, December 30, 1903, a fire in the Iroquois Theater in Chicago, Illinois, kills more than 600 people. It was the deadliest theater fire in American history. Barred fire exits, and the absence of a fire-safety plan caused most of the fatalities.

The Iroquois Theater, designed by Benjamin Marshall in a Renaissance style, was extraordinarily extravagant and had been judged fireproof upon its opening in 1903. George Williams, Chicago’s building commissioner, and fire inspector Ed Laughlin inspected the theater in November 1903 and affirmed that it was “fireproof beyond all doubt.” They also mentioned its 30 exits, 27 of which were double doors. Nevertheless, at the same time, William Clendenin, the editor of Fireproof magazine, also scrutinized the Iroquois and wrote a scornful editorial about its fire hazards, stating that there was a lot of wood trim, no fire alarm with no sprinkler system above the stage.

On December 30, 1903, the Iroquois showed a matinee performance of the fashionable musical Mr. Blue Beard, which had been showing at the theater since opening night. The play was a burlesque of the traditional Bluebeard folk tale. Attendance since opening night had been inadequate; people had been kept away by poor weather, labor unrest, and other factors. The December 30 show drew a large sellout audience. In addition, hundreds more tickets for the “standing room” areas at the theater’s rear were sold. Many of the 2,100-2,200 customers attending the matinee were children. The standing-room areas were so packed that some patrons sat in the aisles, blocking the exits.

At about 3:15 p.m., soon after the start of the second act, eight men and eight women were performing the number “In the Pale Moonlight,” with the stage lit up by blue-tinted spotlights to suggest a night scene. Sparks from an arc light set fire to a curtain, possibly because of an electrical short circuit. However, the lamp operator, William McMullen, later stated that the lamp was too near the curtain, but stage managers failed to fix the problem. McMullen tried to put the fire out when it started, but the flame quickly raced up the curtain and beyond his reach. Theater fireman William Sellers attempted to extinguish the fire with the Kilfyre canisters provided, but by then, it had spread to the fly gallery high above the stage. Several thousand square feet of flammable painted canvas scenery flats hung from the rafters. The stage manager tried to lower the asbestos fire curtain, but it got caught. Early reports assert that the asbestos curtain was halted by the trolley wire transporting one of the acrobats over the stage. Still, later inspection revealed that the curtain had been stopped by a light reflector that pushed out under the proscenium arch. A chemist who later tested part of the curtain maintained that it was mainly wood pulp mixed with asbestos and would have been useless in a fire.

By this time, many customers on all levels struggled to escape the venue. Some had found the fire exits hidden behind draperies but could not open the unaccustomed bascule locks. Bar owner Frank Houseman, a former baseball player with the Chicago Colts, resisted an usher who declined to open a door. He could open the door because his ice box at home had a comparable lock. Houseman credited his friend, outfielder Charlie Dexter, pushing another door open. A third door was opened by brute force or a blast of air, but most of the other doors failed to open. Some customers panicked, crushing or trampling others in a fire effort to flee the fire. Many were killed while confined in dead ends or trying to open what appeared to be doors with windows but were only windows.

Those in the orchestra section escaped into the lobby and out of the front entrance, but those in the dress circle who fled the fireball could not access the lobby because high-fallen people blocked stairwells. The largest death toll was at the base of stairways, where hundreds of people were crushed, trampled, or suffocated. Customers able to get out using the exits on the north side found themselves on fire escapes, one of which was poorly installed, causing people to fall upon departing the fire escape door. Many fell or jumped from the icy, narrow fire escapes to their demises; the bodies of the first jumpers broke the falls of those who came after them.

The Iroquois had no fire alarm box or telephone. The CFD’s Engine 13 was apprised of the fire by a stagehand who had run from the burning theater to the nearest firehouse. On the way to the fire, at 3:33 p.m., a member of Engine 13 triggered an alarm box to call additional units. Aerial ladders proved useless in the alley, and black nets, hidden by the smoke, were impractical.

Mass panic followed, and struggling to escape from the burning building, many trapped inside attempted climbing over mounds of bodies. Corpses were stacked ten feet high around some of the obstructed exits. The victims were suffocated by the fire, smoke, and gases or were squashed to death by the surge of other terrified customers behind them. It is estimated that 575 people died on the day of the fire, with at least thirty more dying of injuries over the following weeks. Of the 300 actors, dancers, and stagehands, only five died.

In the aftermath of the catastrophe, George Williams, Chicago’s building commissioner, was later charged and convicted of misfeasance. Chicago’s mayor was also arrested, though the allegations failed to stick. The theater owner was found guilty of manslaughter due to poor safety measures; the conviction was later appealed and overturned. The only person convicted concerning this fire was a nearby saloon owner who had robbed the dead bodies while his bar acted as a makeshift morgue after the fire.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black’s” Blog to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment