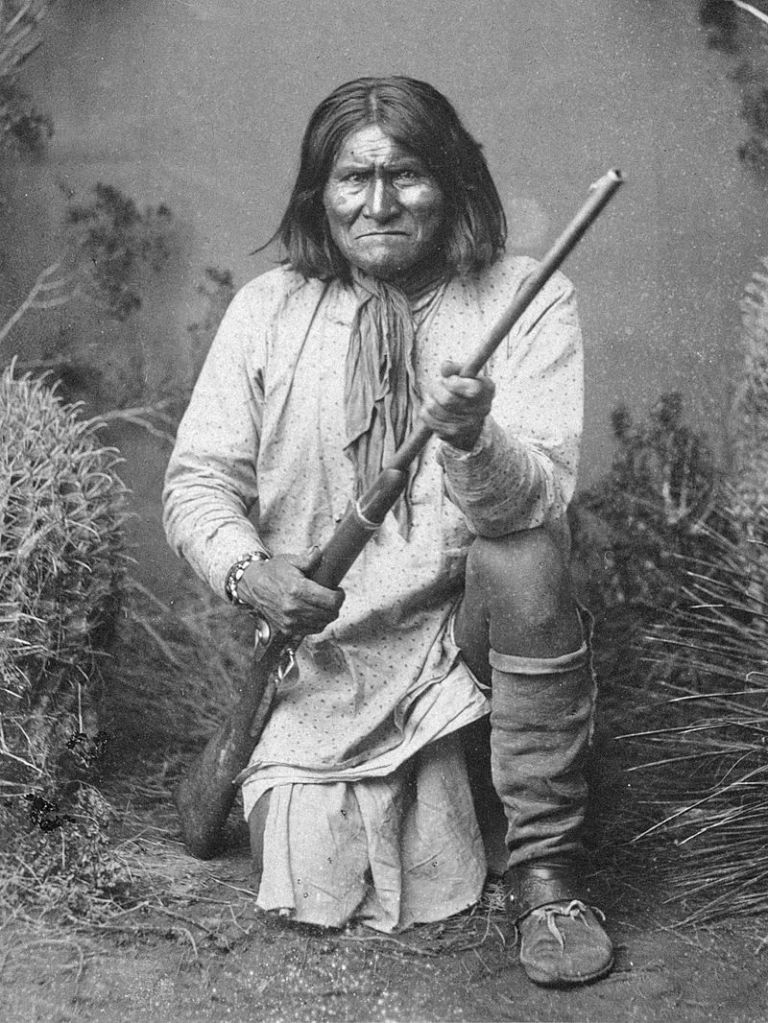

Image: Geronimo (Goyaalé), a Bedonkohe Apache, kneeling with a rifle, 1887. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, February 17, 1909, Geronimo, Chiricahua Apache leader and medicine man, died of pneumonia; while riding home on his horse, he was thrown off. He survived the night out in the cold, but Geronimo’s health was deteriorating rapidly when a friend found him the next day. He passed away six days later, with his nephew at his side.

“I should never have surrendered,” Geronimo, still a prisoner of war, said on his deathbed. “I should have fought until I was the last man alive.”

Geronimo was born in 1829 to the Bedonkohe band of the Apache near Turkey Creek, in the modern-day state of New Mexico, then part of Mexico. However, the Apache did dispute Mexico’s claim to the territory. His given name was Goyaale, meaning “the one who yawns.” How he came to be called Geronimo is a historical mystery with several far-flung explanations floating around out there. His grandfather, Mahko, had been chief of the Bedonkohe Apache.

As a boy, the story goes, Geronimo swallowed the heart of his first kill to ensure a lifetime of success on the chase. Belonging to the smallest band within the Chiricahua tribe, the Bedonkohe (numbering only 8,000 people), they were surrounded by enemies – not just Mexicans but also other tribes, including the Navajo and Comanches. Raiding their neighbors was part of Apache life. As a result, the Mexicans placed a bounty on Apache scalps, but this did little to deter the frequency and viciousness of the raiding. By 17, Geronimo had already led four successful raiding operations.

On March 5, 1851, a group of 400 Mexican soldiers from Sonora under the command of Colonel Jose Maria Carrasco attacked Geronimo’s camp outside Janos, Chihuahua, while the men were in town trading. According to Carrasco, this was in response to a raid that Geronimo and his men conducted at Sonora. Among those killed in Carrasco’s attack at Janos were Geronimo’s wife, three children, and aged mother. The loss of his whole family devastated Geronimo and led him to hate all Mexicans for the rest of his life, even more than Americans. As a show of grief, he set fire to his family’s belongings and then headed into the wilderness to grieve his loss. There, it is said, alone and crying, a voice came to Geronimo that promised him: “No gun will ever kill you. I will take the bullets from the guns of the Mexicans… and I will guide your arrows.”

Feeling invigorated by this newfound power, Geronimo gathered a force of 200 men and stalked the Mexican soldiers who killed his family. This continued for the next ten years as Geronimo exacted his revenge against the Mexican government.

By the 1850s, the face of the enemy had changed. With the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the United States took over large amounts of land from Mexico, including areas belonging to the Apache. The discovery of gold in the Southwest spurred many settlers and miners to move into the territory, thus causing friction with the Apache and other Native Americans. Geronimo kept up his raiding ways, and by 1877 Geronimo was caught by the American Army and banished to the San Carlos Apache reservation. He struggled with reservation life for four years until 1881, when he finally escaped.

Over the next five years, Geronimo and his small band of Chiricahua eluded American soldiers. Perceptions of Geronimo were nearly as complicated as the man himself. His followers saw him as the last great defender of the Native American way of life. Yet others, including several fellow Apaches, viewed him as a stubborn holdout, violently driven by revenge and foolishly putting the lives of people in constant danger. At one point, nearly one-quarter of the American Army and 3,000 Mexican soldiers were engaged in the effort to hunt him down.

By September 1886, after having grown tired of the chase, Geronimo finally surrendered, this time for good. The rest of the Chiricahua Apache had been captured and sent to Florida, including some of his wives and children (Geronimo would marry nine times over his lifetime). General Nelson Miles pledged to Geronimo that he would be reunited with his family in Florida, but this would not occur for two more years.

Geronimo would spend the remaining 27 years of his life as a prisoner of war with the American government. He would never be free again. Later, he became a celebrity, with people paying for the privilege of seeing him. He would sell them photos of himself and hats that he had worn. He would even allow his picture to be taken with tourists for a fee. They would even pay 25 cents for a button off his coat.

In 1905 Geronimo rode horseback down Pennsylvania Avenue in President Theodore Roosevelt’s Inaugural Parade. He rode with five other chiefs and wore a headdress and painted faces. Later in the week, Geronimo met with President Roosevelt and asked him for permission to be relieved of their status as prisoners of war and return to their homeland in Arizona. President Roosevelt refused, speaking about the continued animosity that the people of Arizona had against Geronimo and the Apache who took part in the Apache Wars. Through an interpreter, Roosevelt told Geronimo that the Apache had a “bad heart .”You killed many of my people; you burned villages…and were not good Indians.” Roosevelt then told him he would “see how you and your people act” on the reservation.

He died on a reservation at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, on February 17, 1909, at age 79.

A legend is spoken of until this day that Geronimo may have managed one final escape. When an army reporter visited the monument to Geronimo at Fort Sill in 1943, he spoke to an elderly Apache man who claimed that not long after Geronimo died, some Chiricahua compatriots removed his body from Fort Sill and took it back to the Apache homeland in the rugged desert of the Southwest. Even in death, Geronimo had eluded his captors.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black’s” Blog to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment