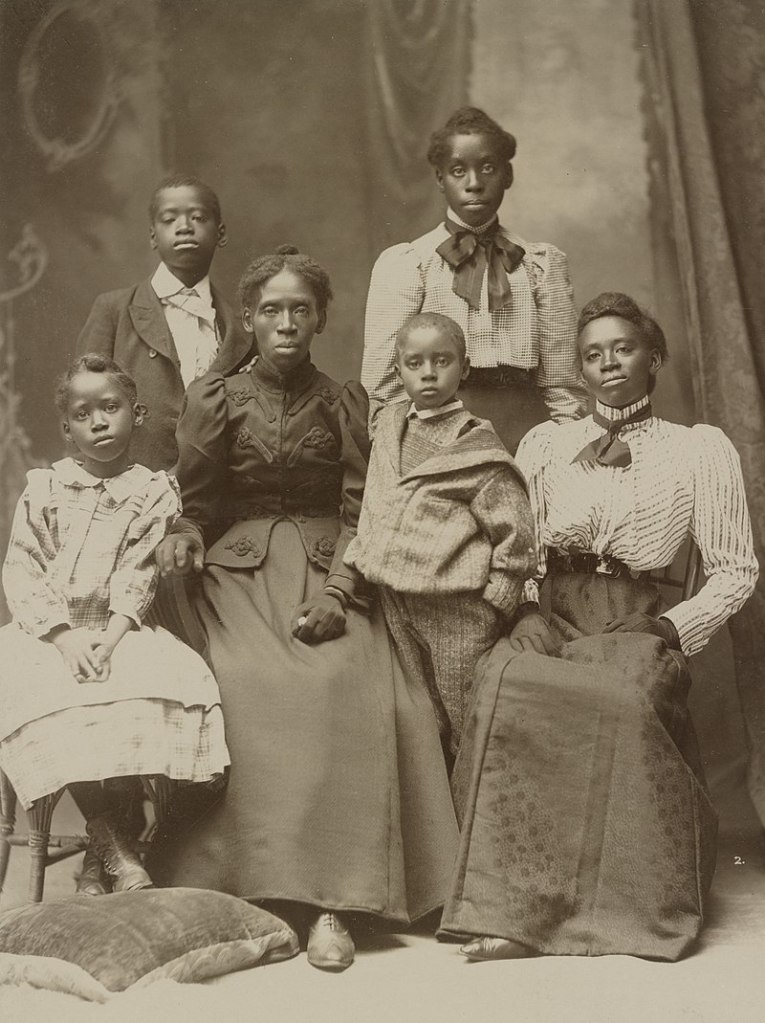

Image: Lavinia Baker and her five surviving children. A mob of whites had set fire to their house at night and fatally shot and killed her husband, Frazier Baker, and baby girl Julia on February 22, 1898. Left to right: Sarah; Lincoln, Lavinia; Wille; Cora, Rosa. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, February 22, 1898, U.S. Postmaster Frazier B. Baker and his two-year-old daughter Julia Baker were lynched and died at their home in Lake City, South Carolina, after a white mob attack on their home. The mob set fire to the Baker home in an effort to drive them out. Baker’s wife and two of his other children were hit by gunfire and were wounded but managed to escape the burning house.

When the attack started at 1:00 AM on February 21, 1898, the fire had consumed the rear wall of the Baker home, which also contained the local post office. Frazier Baker knew precisely what the fire had meant. Born in nearby Effingham, he had assumed the postmastership of Lake City as a patronage appointment brought about by the state Republican Party establishment several months before. Local whites, angry by the elevation of a black man – and an “outsider” to boot – to a position of authority, had burned down the first post office building Baker maintained, had shot his black assistant, and had made repeated threats on his life. After the 1896 Presidential election, William McKinley’s Republican administration appointed hundreds of blacks to postmasterships across the American South. These appointments were opposed by local whites, who disliked any black Republican officeholders. They felt that the increased political power of black postmasters would encourage them to proposition white women. The people of Lake City, South Carolina, had had enough, and they were doing something about this affront to civilized society, or so they thought.

As the smoke thickened that night, Baker’s eldest son Lincoln opened the front door to cry out for help, only to retreat when several gunshots rang out. They could not douse the fire with what little water they had on hand. Baker told his wife, Lavinia, “We might as well die running as…standing still.” He attempted to take his family safely out of the inferno, but backlit by the flames, he was an easy target for the well-armed whites congregated around the front of the house who opened fire. Frazier Baker, postmaster, collapsed, fatally wounded in the deluge of bullets. Whites continued to fire, inflicting severe gunshot injuries on the children Rosa, Cora, and Lincoln before they could run from their home into the sheltering darkness. (Two other children, Sarah and Willie, were miraculously unharmed.) Lavinia tried to follow, holding their infant daughter Julia, but a bullet passed through her hand, killing the baby and forcing her to drop the child from her arms. Struck in the leg by a second bullet, Lavinia Baker collapsed outside the building as the flames consumed the house and the bodies of her husband, Frazier, and daughter Julia. As the white mob left, local African Americans drawn by the gunfire offered refuge in their homes to the new widow and her five surviving children.

The lynching was rebuked by many in the country, including across the South. Those in the South, though, agreed with South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman, who stated that the “proud people” of Lake City refused to receive “their mail from a n****r.” Journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett condemned the murders and said the mob had not even pretended Baker had committed a crime. She organized mass protests in Chicago and even met with President McKinley, telling him that Baker’s murder “was a federal matter, pure and simple. He died at his post of duty in defense of his country’s honor, as truly as did ever a soldier on the field of battle.”

The lynching of the Bakers had to compete for newspaper coverage with the sinking of the USS Maine, which had occurred a few days before. White newspapers in South Carolina called the murders “dastardly” and “revolting,” while the Williamsburg County Record characterized the matter as “the darkest blot upon South Carolina’s history.” It also stated that the McKinley administration was also guilty of “thrusting venal negro henchmen into Southern offices of trust.”

A grand jury was assembled in Williamsburg County, but no indictments were returned. The McKinley administration conducted a vigorous investigation into the murders, even offering $1500 ($48,858 today) for information leading to the arrest and conviction of any members of the white mob. Even though witnesses refused to testify, prosecutors indicted seven men for killing Frazier Baker and his daughter, Julia. Eventually, thirteen men were indicted on charges of murder, conspiracy to commit murder, assault, and the destruction of mail on April 7, 1899, after two men turned state’s evidence in exchange for immunity.

The trial occurred in federal court from April 10-22, 1899. There was an all-white jury presiding over the trial. Witnesses told how events transpired that evening, and despite testifying against their neighbors, they showed no remorse for the events of that evening. Henderson Williams, an African American witness, testified that he had seen a group of white men at the post office on the night of the lynching. Williams was threatened and fled Lake City after a local businessman threatened to “do (him) like they did Baker.”

The jury deliberated for about 24 hours before declaring a mistrial; the jury was hopelessly deadlocked in reaching a verdict of five to five. The case would never be retried.

Following the mistrial, Lake City whites petitioned for the post office to be reopened and mail service restored. Local African Americans ridiculed this request as hypocritical.

Lavinia Baker and her five remaining children were assisted by Charleston doctor Alonzo C. McClennan, who chaired a committee in charge of the Baker’s welfare. Eventually, the Baker family moved to Boston, where a house was purchased for them. In Boston, they remained out of the public eye. The surviving Baker children would fall victim to a tuberculosis epidemic, with four children, William, Sarah, Lincoln, and Cora, dying from the disease between 1908 and 1920. Rosa Baker, the last surviving child, would die in 1942. After her last child died, Lavinia moved back to South Carolina, where she lived until she died in 1947.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black’s” Blog to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment