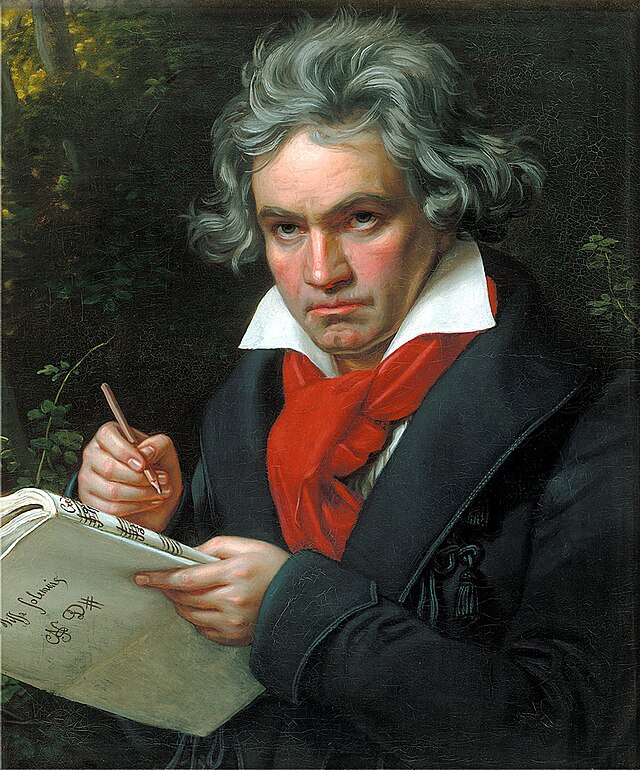

Image: Ludwig van Beethoven (Public Domain)

On this day in history, March 26, 1827, German pianist and composer Ludwig van Beethoven dies in Vienna at 56. He is widely deemed one of the greatest musical geniuses of all time. His groundbreaking compositions blended vocals and instruments, expanding the sonata, symphonies, concertos, and quartets range. His works are amongst the most played in the classical music collection and span the transition between the Classical and Romantic periods in classical music. A battle against deafness marred Beethoven’s personal life, and some of his most important works were composed during the last ten years of his life when he was deaf.

Beethoven was born in Bonn, archbishopric of Cologne (Germany), on or about December 16, 1770. Although his date of birth is unknown, Beethoven was baptized on December 17, 1770. Baptizing babies within 24 hours of birth was customary, so December 16 is his most probable birthdate. Of Johann and Maria Magdalena von Beethoven’s seven children, only Ludwig, the second-born, and two younger brothers survived into adulthood: Kaspar, born in 1774, and Johann, born in 1776.

Ludwig’s father, Johann van Beethoven, was an unexceptional court singer known more for his alcoholism than his musical ability. His mother, Maria Magdalena Beethoven, was a slender,

sophisticated and profoundly moralistic woman.

Beethoven’s father began teaching him music with astonishing vigor and ruthlessness that affected him for the rest of his life. Neighbors stated that they often observed the young boy crying while playing the clavier, standing atop a footstool to reach the keys, and his father thrashing him for each hesitation or error. Almost daily, Beethoven was flogged, locked in a cellar, and deprived of sleep for several hours of practice. His father taught him the violin and clavier, and he took additional lessons from organists around town. Despite or because of his father’s oppressive methods, Beethoven was an immensely talented musician from his earliest days.

Beethoven’s father hoped the young Ludwig would be compared to the musical prodigy Wolfgang Mozart. He arranged his first public recital for March 26, 1778, and he billed it as “a little son of 6 years,” even though he was in years 7-years-old. Beethoven played well, but his recital received no press whatsoever.

At school, Beethoven was an average student. Some biographers have stated that he was mildly dyslexic. He said, “Music comes to me more readily than words.” In 1781, at age 10, Beethoven withdrew from school to study music full-time with Christian Gottlob Neefe, the newly appointed Court Organist. At 12, Beethoven published his first composition, a set of piano variations built on a theme by an obscure classical composer named Dressler.

There is no conclusive evidence to prove that Beethoven ever met Mozart. In 1787, the court dispatched Beethoven to Vienna to facilitate his musical development, where he had hoped to study with Mozart. After hearing Beethoven, Mozart said, “Keep your eyes on him; someday, he will give the world something to talk about.” After a little while in Vienna, Beethoven’s mother died, and he returned home to Bonn. Remaining there, Beethoven continued to build his reputation as the city’s most promising young musician.

In 1792, Beethoven returned to Vienna, and he began to study piano with Haydn, vocal composition with Antonio Salieri, and counterpoint with Johann Albrechstberger. Not yet recognized as a composer, Beethoven rapidly created a reputation as a virtuoso pianist who was remarkably gifted at improvisation.

He made his long-awaited public debut in Vienna on March 29, 1795. He is believed to have played his “first” piano concerto in C Major. Then he published three piano trios and named it his Opus 1, an enormous critical and financial success. Beethoven composed many pieces that marked him as a great composer. It was also around 1801 that Beethoven discovered he was losing his hearing.

Beethoven never married or had children. He was, however, madly in love with a married woman named Antonie Brentano. Over two days in July 1812, Beethoven wrote her a long, beautiful love letter he had never sent. Addressed “to you, my immortal Beloved,” the letter stated in part, “My heart is full of so many things to say to you – ah – there are moments when I feel that speech amounts to nothing at all – Cheer up – remain my true, my only love, my all as I am yours.”

The demise of Beethoven’s brother Kaspar in 1815 created one of the great trials of his life, a prolonged legal battle with his sister-in-law, Johanna, over the custody of Karl von Beethoven, his nephew and her son. The struggle stretched for seven years, during which both sides spewed hateful speech at each other. Ultimately, Beethoven won the boy’s custody, though not his affection.

Despite his extraordinary output of magnificent music, Beethoven was lonely and miserable throughout most of his adult life. Beethoven quarreled with his brothers, publishers, housekeepers, pupils, and patrons; he was absent-minded, short-tempered, greedy, and suspicious to the point of paranoia.

By the turn of the 19th century, Beethoven was trying to come to terms with and hide the fact that he was going deaf. In a letter to his friend Franz Wegeler in 1801, he showed, “I must confess that I lead a miserable life. For almost two years, I have ceased to attend any social functions just because I find it impossible to say to people: I am deaf. If I had any other profession, I might be able to cope with my infirmity; but in my profession, it is a terrible handicap.”

Almost astoundingly, despite his rapidly growing deafness, Beethoven continued to compose at a furious rate despite frequent and prolonged bouts of illness during the last part of his life.

Beethoven’s death occurred on March 26, 1827, at 56, of post-hepatitic cirrhosis of the liver. An autopsy revealed Beethoven had major liver damage, most likely because of his heavy drinking and substantial dilation of the auditory and other related nerves.

Summing up his life and impending death during his last days, Beethoven, who was never as eloquent with words as music, borrowed a tagline that concluded many Latin plays at the time. Plaudite, amici, comoedia, finita est, he said. “Applaud friends, the comedy is over.”

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black’s” Blog to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment