Subscribe to get access

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

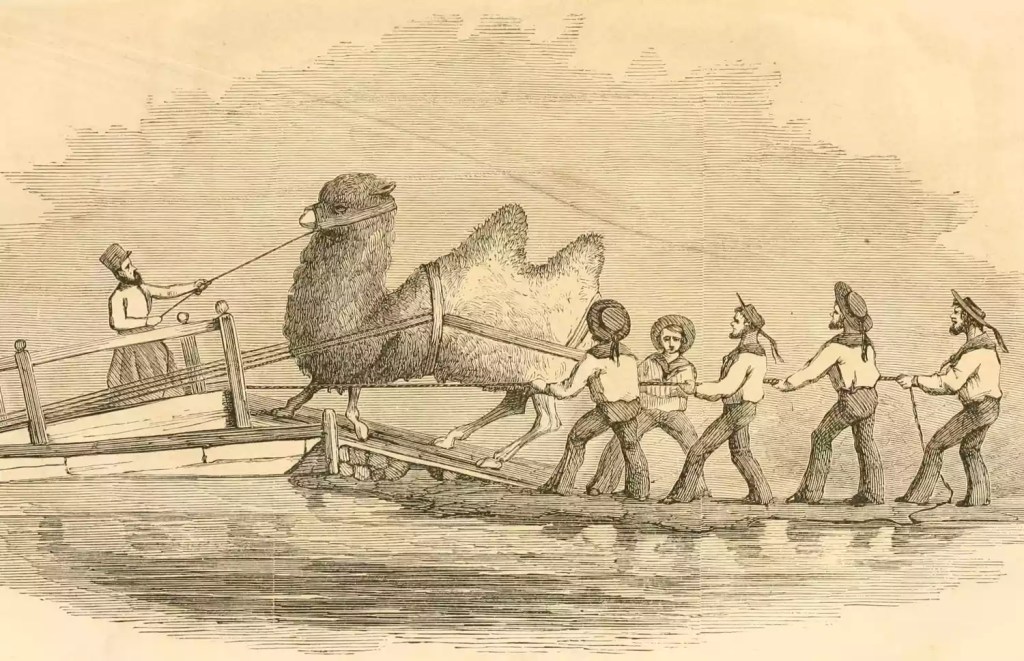

Image: Sailors of USS Supply loading a camel aboard.

In the 1850s, the U.S. Army conceived a plan to bring several camels from the Middle East into the United States and employ them to travel through large tracts of the American Southwest carrying cargo for the military. As improbable as this seems, it did actually happen.

The project, conceived by Jefferson Davis, was initially thought to hold great promise. In the 1850s, Davis was a powerful Washington political force who would eventually become the President of the Confederate States of America. At this time, Davis was the secretary of war in President Franklin Pierce’s cabinet.

The use of camels in the Southwest of America looked very promising to Davis because the War Department had a big problem to solve. After the Mexican War ended, the United States took over large amounts of unexplored land in the Southwest. And there existed no simple way to travel in the region. At that time, in what is now Arizona and New Mexico, there were absolutely no roads to speak of. Travelling off any pre-existing trail meant the explorer was moving into the country with formidable terrain ranging from deserts to mountains. Water and pasture for horses, mules, or oxen were non-existent or, at best, very hard to find.

The camel had gained a reputation for toughness and its ability to survive in extreme conditions. Even as early as the 1830s, the U.S. military had considered using camels, this time during the Seminole War in Florida.

The reports from the battlefields of the Crimean War had given the U.S. Army hope regarding camels. A few of the armies had employed camels as pack animals, and they were reported to be stronger and more dependable than mules or horses. Because the French and Russian troops were using camels successfully, this gave the idea credence in the minds of U.S. military planners.

On December 9, 1853, Secretary of War Davis wrote a lengthy report that took up more than an entire page of the New York Times. Buried in the details of his many requests for Congressional funding are several passages that attempt to make the case for securing funds for a study into the military use of camels.

The paragraphs in The Times show that Davis had been using two types of camels, the one-humped dromedary (often referred to as the Arabian camel) and the two-humped Asian camel (better known as the Bactrian camel):

“On the older continents, in regions reaching from the torrid to the frozen zones, embracing arid plains and precipitous mountains covered with snow, camels are used with the best results. They are the means of transportation and communication in the immense commercial intercourse with Central Asia. From the mountains of Circassia to the plains of India, they have been used for various military purposes: to transmit dispatches, to transport supplies, to draw ordnance, and as a substitute for dragoon horses.

“Napoleon, when in Egypt, used with marked success the dromedary, a fleet variety of the same animal, in subduing the Arabs, whose habits and country were very similar to those of the mounted Indians of our Western plain. I learn, from what is believed to be reliable authority, that France is about again to adopt the dromedary in Algeria, for a similar service to that in which they were so successfully used in Egypt.

“For like military purposes, for express and for reconnaissances, it is believed the dromedary would supply a want now seriously felt in our service; and for transportation with troops rapidly moving across the country, the camel, it is believed, would remove an obstacle which now serves greatly to diminish the value and efficiency of our troops on the western frontier.

“For these considerations, it is respectfully submitted that the necessary provision be made for the introduction of a sufficient number of both varieties of this animal to test its value and adaptation to our country and our service.”

-New York Times, December 9, 1853.

Finally, on March 3, 1855, a military appropriations bill was passed. Davis received his request for $30,000 to purchase several camels and begin a program to assess their usefulness in the United States Southwest.

With caution thrown to the wind, the camel project had suddenly been given enormous priority within the American Army. Lieutenant David Porter, a promising and capable naval officer, was given command of the ship sent to bring the camels back to the United States from the Middle East. Porter continued to be a critical player in the Union Navy during the Civil War, and as Admiral Porter, he became a highly regarded figure in the late 19th-century United States.

Major Henry C. Wayne, an American Army officer, was tasked with learning about camels and acquiring them for the military. Wayne, a West Point graduate, had been decorated for bravery in the Mexican War. He would later fight for the Confederate Army during the Civil War.

In 1855, Davis ordered Major Wayne to sail to London and Paris to seek the advice of various camel experts. Davis also managed to secure a U.S. Navy transport ship, USS Supply, which accompanied them to the Mediterranean area under Lt. Porter’s command. The pair of officers would meet up and then sail to various Middle Eastern locales in search of camels to purchase.

On May 19, 1855, Major Wayne sailed on a passenger ship from New York to England. The USS Supply, meanwhile, had been outfitted with stalls for camels and a robust supply of hay, and it left the Brooklyn Navy Yard the week after.

While in England, Major Wayne met with the American consul, future president James Buchanan. Wayne also visited the London Zoo, where he learned how to care for camels. From there, he travelled to Paris, where he met with French military officers who were familiar with using camels for military purposes. On July 4, 1855, Wayne wrote a long letter to Secretary of War Davis informing him of what he had learned during his inquiries about camels.

By July’s end, Wayne and Porter had linked up and begun their quest for camels. Their first stop was Tunisia, where they purchased one camel and were gifted two camels by the country’s leader, the Bey, Mohammad Pasha. In early August 1855, Wayne informed Jefferson Davis that they had secured three camels safely aboard the ship and at anchor in the Gulf of Tunis.

For the next seven months, Wayne and Porter travelled from port to port in the Mediterranean, trying to purchase camels. They regularly reported to Jefferson Davis in Washington, expounding on their latest travels.

While travelling through Egypt, Syria, and Crimea, the two officers became adept at camel trading. Sometimes, they were sold sick and unwell camels. In Egypt, one government official attempted to sell them camels that the Americans knew were unsatisfactory. Two camels they had purchased but were substandard had to be disposed of by being sold to a butcher in Cairo.

By February 1856, the group acquired 31 camels and two calves and began sailing for the United States. Also on the ship with Wayne and Porter heading to Texas were three Arabs and two Turks, who had been hired to help care for the camel herd. The trip across the Atlantic was fraught with inclement weather, but the group and their camels finally made it to Texas in early May 1856.

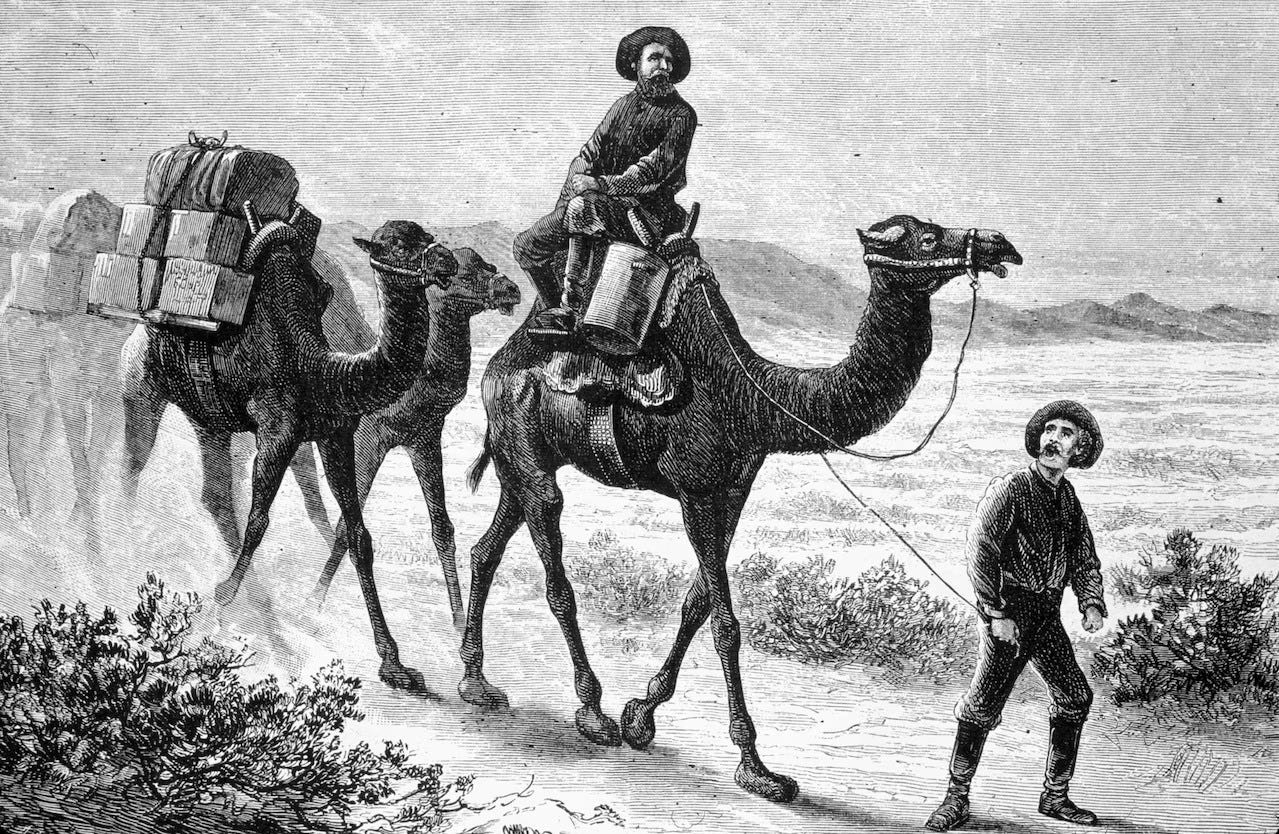

Image: Newly imported camels carry soldiers and supplies in the 1857 U.S. Army Camel Corps expedition. Slaveholders hoped that the desert animals would facilitate the westward expansion of slavery.

Since only a tiny amount of the Congressional allotment of money had been spent, the War Secretary, Jefferson Davis, ordered Lieutenant Porter to sail back to the Mediterranean area aboard USS Supply, acquire another load of camels, and return to Texas. Major Wayne would stay in Texas, putting the first group of camels through a series of trials.

In mid-1856, Major Wayne took the camels from the port of Indianola to San Antonio. From there, he took them to Camp Verde, an army outpost about 60 miles southwest of San Antonio. There, Wayne started using the camels for routine jobs, such as carrying supplies from San Antonio to Camp Verde. He soon learned that the camels could handle much more weight than a pack mule, and with a bit of instruction, soldiers had no problem dealing with them.

When Porter returned from his second voyage to the Mediterranean, he had managed to secure an additional 44 camels. The U.S. Army now possessed about 70 camels of differing types. (Some of the calves that had been born were thriving, while some adult camels had died.)

After the initial trials with camels at Camp Verde were deemed successful, Jefferson Davis wrote a full report on the effort, which was eventually published as a book in 1857. When Franklin Pierce left office and was no longer President, and James Buchanan became Commander-in-Chief in March 1857, Davis was out of a job at the War Department.

The incoming secretary of war, John B. Floyd, felt that the camel project was practical, and he tried to gain congressional support to purchase another 1,000 camels. But his project received absolutely no support on Capitol Hill. Subsequently, the U.S. Army only ever brought the original two boatloads of camels to the United States.

By the late 1850s, the military and the government of the United States were more concerned about the potential for inner strife than about camels. Jefferson Davis, who had returned to the U.S. Senate representing Mississippi, was the biggest supporter of the camel experiment. Davis gave little thought or care to the camel issue as the nation approached the Civil War.

In the meantime, back in Texas, the “Camel Corps,” the once promising project, encountered several problems. A portion of the herd was sent to remote outposts to be utilized as pack animals, yet some soldiers disliked using them. Also, there were problems stabling the camels near horses, who became increasingly agitated by their presence.

By late 1857, Army Lieutenant Edward Beale was tasked with making a wagon road from a fort in New Mexico to California. Beale used about 20 camels and other pack animals for the task and reported that the camels performed exceedingly well.

Over the next few years, Lieutenant Beale used camels during exploratory expeditions in various parts of the Southwest. When the Civil War began, he took his herd of camels to a military base in California.

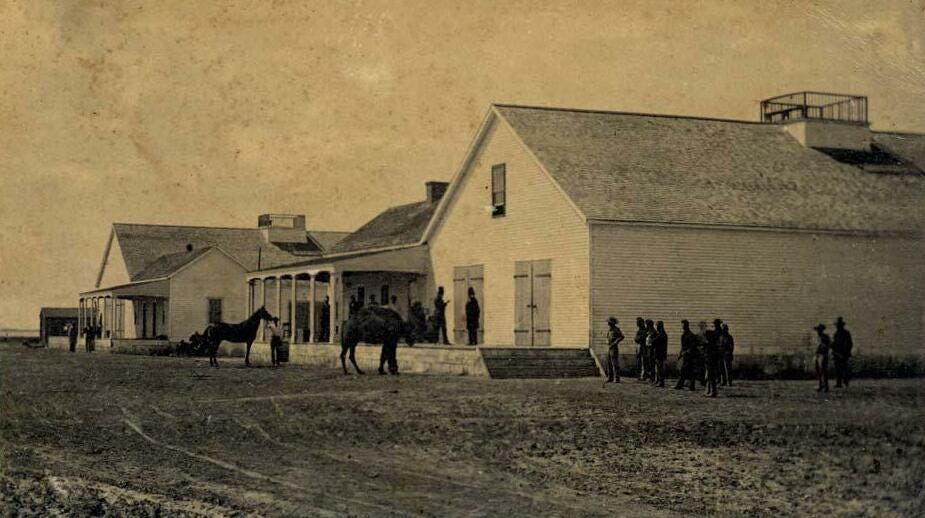

Image: Only known surviving photo of the U.S. Camel Corps. The caption reads, “A member of the legendary southwestern ‘Camel Corps’ stands at ease at the Drum Barracks military facility, near California’s San Pedro harbour.” 1863.

Throughout the Civil War years, there were some novel experiments, like Lincoln’s use of the telegraph, the Balloon Corps, and inventions like the ironclads. Yet, no one revived the idea of using camels in the military.

For the most part, the camels in Texas fell into Confederate hands and were not used for any military purpose during the Civil War. Many are thought to have been sold to traders and owned by Mexican circuses.

While the Army brought camels into Texas, private businesses imported hundreds through Mobile, Galveston, and San Francisco ports, hedging their bets on an impending boom market out West for the beasts. Those commercially imported camels began to mix with the Army camels in the 1870s. The mixed herds made it very difficult to track the offspring of the Army camels.

In 1864, the U.S. Army herd of camels in California was ultimately sold to a businessman who then unloaded them to zoos and travelling shows. Many were utilized in Southwestern American mining towns. At the same time, an unlucky few were sold to meat markets and butchers, while a number of the camels were moved to Arizona to perform with the construction of a transcontinental railroad. When that railroad opened, it quickly snuffed out hopes for a camel-based freight business in the Southwest. Owners who didn’t dispose of their herds to travelling entertainers or zoos reportedly freed them to roam the desert in the Southwest region. For many years, cavalry troops occasionally reported seeing small groups of wild camels.

If you enjoy my history content, you can support my work with a donation at https://buymeacoffee.com/francischao

Leave a comment