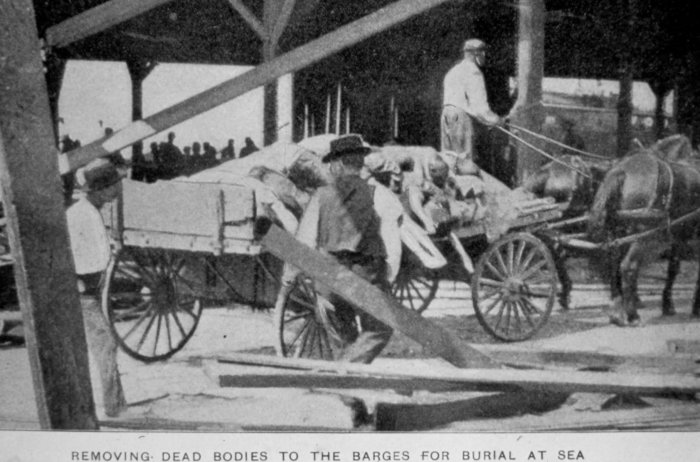

Image: Many who died had their corpses piled onto carts for burial at sea. (Wikimedia Commons.)

On this day in history, September 8, 1900, one of the deadliest hurricanes in American history hits Galveston, Texas, killing between 6,000-12,000 people. The storm caused so much destruction on the Texas coast that reliable estimates of the number of victims are difficult to make. This was by far the deadliest weather event in U.S. history.

Galveston Island lies just off the Texas coast. It is long and narrow, about 28 miles long by 2 miles wide, and is barely above sea level. The harbor on the bay side of Galveston was a prime port with numerous rail connections. As a central hub for trade, thousands of people settled on the island at the end of the 19th century.

It was a Friday afternoon when the residents of Galveston first got an indication that a storm was imminent. The storm had been bearing down on the Texas coast for a few days, coming across the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Keys. And, worst of all, virtually nobody had the foresight to evacuate.

At the time, there was no reliable warning system in place for hurricanes; it was not until 1908 that ships began radioing the mainland about approaching storms. Winds 120 miles per hour hit the city with flying debris that cut through homes like shrapnel. Waves crashed onto the streets, leaving the city 15 feet underwater.

Galvestonians had experienced ocean floodwaters from storms before, but they had yet to do much more than board up windows and build beach houses off the ground as prevention. This lack of preparation would cost them dearly.

The first indication that trouble was coming occurred on August 27, when a ship about 1,000 miles off the West Indies reported “unsettled” weather – which was considered nothing to worry about. Antigua saw thunder, and Cuba got quite a lot of rain in the next few days, but the tropical storm that hit Florida was only a small portion of what it would become.

The problem was the Gulf of Mexico: its waters were very warm that summer, and conditions were excellent for turning a tropical storm into a monster hurricane. But American meteorologists disregarded the warnings from Cuba because they didn’t think the storm was headed towards them.

They were convinced the storm was heading northeast, up the East Coast, and into calmer Atlantic waters, and nothing Cuban meteorologists said would convince them otherwise (tensions were running very high in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War).

It came as a complete surprise, then, when on September 6, Captain Halsey of The Louisiana reported that he and his shipmates had run into a hurricane shortly after they left New Orleans – in Gulf Coast waters. The news was especially startling because no other sources were reporting it. With telegraph lines knocked down and destroyed, word that the Louisiana and Mississippi coasts had suffered heavy damage was incredibly slow to circulate.

This is why Galveston residents didn’t evacuate: they had no idea they should.

On Friday, September 7, the Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) issued Galveston a storm warning. As the sun set that evening, immense swells rose in the Gulf, and clouds began to roll in from the north.

The following morning, a single-paragraph story with the headline “Storm in the Gulf” appeared in the newspaper, which caused the citizens little concern. Residents were similarly complacent when Galveston’s Weather Bureau raised its hurricane flags. After all, people said, Galveston had survived storms before – it would survive them again.

Nothing in the reporting indicated that the Galveston Hurricane would be a different kind of storm – unlike anything the Gulf Coast had seen before.

The storm hit Galveston on Saturday, September 8, with sustained winds of at least 120 miles per hour; the town’s wind gauge blew away so that the wind speed may have been even higher. A Category 4 hurricane brought an enormous storm surge and waves that were 15 feet higher than the mean tide. At the Bolivar Point lighthouse, there was a report that saltwater spray from the ocean reached a height of 115 feet. Buildings crumbled and fell from the force of the water, and high winds ripped the roofs off nearly every building in town. Many Galveston businesses and families had installed slate roofs after a severe 1885 fire, and these roofs became flying weapons of destruction as the hurricane tossed them through the air.

The St. Mary’s Orphanage collapsed and killed all the inhabitants. At the Ursuline Convent, 1,000 people gathered seeking shelter, but when a 10-foot retaining wall fell, the whole front part of the convent collapsed. Ships in the harbor were tossed into each other, and some were later found 30 miles away. Survivors reported seeing corpses floating all over and around the island. Thousands died in Galveston, and at least another 2,000 on the mainland coast also perished. Precise numbers will never be known, partly because thousands of bodies were disposed of in the Gulf of Mexico without being counted or identified. When Clara Barton of the Red Cross came to Galveston soon after the disaster, she said, “It would be difficult to exaggerate the awful scene here.”

Galveston began to rebuild almost immediately. On October 2, 1902, construction began on a massive protective sea wall. Two years later, the wall was complete, 16 feet thick by 17 feet high, and constructed of cement, stone, and steel bars. By 1910, the population of Galveston had grown to 36,000. Thanks to the city’s preparations, only eight people died when a comparable storm hit in 1915.

Subscribe to History Daily with Francis Chappell Black for daily updates:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment