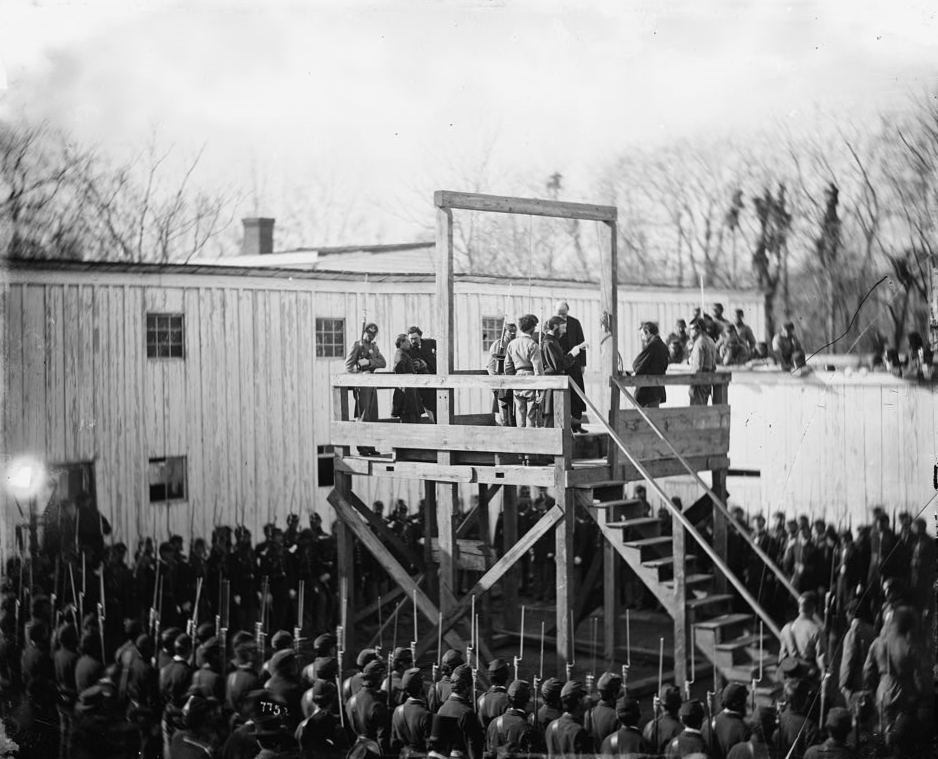

Image: The execution of Henry Wirz, commandant of the (Confederate) Andersonville Prison, near the US Capitol moments after the trap door was sprung. Washington, D.C. (Public Domain)

On this day in history, November 10, 1865, Henry Wirz, a Swiss immigrant and the commanding officer of Andersonville prisoner of war camp in Georgia, is hanged for the murder of Union soldiers interned there during the American Civil War.

A few minutes past 10 a.m., on November 10, 1865, former Andersonville prison camp commander Captain Henry Wirz strode quickly from the Old Capitol Prison in Washington D.C., where he had been incarcerated since his seizure in May after a military court had found him guilty of violating the rights of prisoners according to the regulations of war and where he had waited to be executed by hanging.

Visible to him was the scaffolding with trap door and noose, and gathered around the tower was a crowd of 200 onlookers, including officials and representatives of the press. On top of the prison walls and the roofs of nearby houses, more observers viewed and yelled, “Hang the scoundrel!” and “Remember Andersonville,” according to news reports.

Through it all, Wirz continued to sport a thin smile, and the papers remarked positively on his relaxed disposition.

Wirz’s life was nearing its end; he had become the most reviled Confederate officer in the North after the Civil War. All the rage at the abuse and killing of Union soldiers held in Confederate prisoner-of-war camps anywhere in the South was concentrated on Wirz. Months of trial proceedings had created daily features about the severe malnourishment and exposure deaths of about 13,000 Union prisoners held at Camp Sumter, the official name for the prison camp in Sumter County, Georgia, near the town of Andersonville.

Wirz was born in 1823 in Switzerland and moved to the United States in 1849. He resided in Louisiana and became a doctor. When the Civil War erupted, he enlisted with the Fourth Louisiana Battalion. In July 1861, after the First Battle of Bull Run, Virginia, Wirz watched over prisoners in Richmond, Virginia, and was observed by Inspector General John Winder. Winder had Wirz reassigned to his division, and Wirz spent the remainder of the war working with prisoners of war. He was the commander of a prison camp in Tuscaloosa, Alabama; accompanied prisoners around the Confederacy; processed prisoner exchanges with the Union; and was injured in a stagecoach crash. After returning to duty, he journeyed to Europe and transported communications to Confederate emissaries. When Wirz landed in the Confederacy in early 1864, he was assigned to command Andersonville prison camp, officially known as Camp Sumter.

While both sides imprisoned soldiers under terrible circumstances, Andersonville was remarkable for the brutal conditions under which its prisoners were retained. The prison held thousands of men on a deserted, contaminated scrap of ground. Barracks were considered but never constructed; the men slumbered in improvised shelters, called “shebangs,” constructed from scrap wood and blankets that offered no safeguard from the weather. A small stream ran through the complex and supplied water for the Union soldiers, but this developed into a cesspit of disease and human waste. Erosion began by the prisoners turned the stream into a vast marsh. The prison was intended to hold 10,000 men, but the Confederates had filled it with more than 31,000 prisoners of war by August 1864.

Wirz administered an operation in which thousands of prisoners perished. Partially a victim of circumstance, he was allotted few resources from his superiors with which to work, and the Union stopped exchanging prisoners in 1864. As the Confederacy started to crumble, food and medicine for prisoners became hard to acquire. When news about Andersonville became public, Northerners were appalled.

Wirz was accused of conspiracy to damage the health and lives of Union soldiers and homicide. His trial started in August 1865 and lasted for two months. During the trial, over 160 witnesses were summoned to testify. However, Wirz did display indifference toward’s Andersonville’s prisoners. He was partly a scapegoat, and some evidence against him was falsified completely.

Wirz stated he was innocent of the accusations and was a pawn of a shattered prison camp system. There is evidence to uphold him on a portion of that. Although he is frequently said to be the man in charge at Andersonville, he had little control. Management of the camp was fractured. Wirz was only in charge of the campgrounds and was responsible for taking roll, maintaining security, and issuing rations and supplies. A different officer was in command of the overall post of Camp Sumter, while others were responsible for ordering food and supplies – the quartermaster’s office – and operating the hospital. In addition, each guard regiment had its own command staff, and those officers outranked Wirz.

Nevertheless, Wirz could find fault with all the others in managing the camp and his superiors. However, in the end, he was held responsible for his actions and how he treated prisoners.

After his execution, Wirz became a martyr for some in the Confederacy who said he had been a fall guy for the Confederate effort and pointed out he was the only Southern officer prosecuted for war crimes. In fact, he was not. Major John Gee, an officer at the Salisbury prisoner of war camp, was indicted for crimes like Wirz’s but was found not guilty in the spring of 1866. General Ulysses Grant intervened in the trial of Bradley Johnson, another of Salisbury’s officers arrested and who faced negligence accusations. Grant would not permit the prosecution to go ahead.

And then there was a man who controlled the Andersonville quartermaster’s office, James Duncan, who was arrested for manslaughter and convicted by a military tribunal of intentionally withholding food from the prisoners. He was condemned to hard labor at Fort Pulaski and escaped prison a year later.

Wirz was found guilty and condemned to die on November 10 in Washington, D.C. Allegedly, Wirz was offered his life in return for verification that Confederate President Jefferson Davis had known of and authorized the starvation and abuse of Union prisoners. As a matter of honor and principle, he refused. When Wirz was led out to the gallows, rows of Union troops stood in tight formations to witness the death of the man known as the “Demon of Andersonville.”

Wirz supposedly told the officer in charge on the scaffold, “I know what orders are, Major. I am being hanged for obeying them.” The 41-year-old Wirz was among the few people found guilty and executed for crimes committed during the Civil War.

Subscribe to “History Daily with Francis Chappell Black” to receive regular updates regarding new content:

Help us with our endeavors to keep History alive. With our daily Blog posts and our publishing program we hope to inform people in a comfortable and easy-going manner. This is my full-time job so any support you can give would be greatly appreciated.

Leave a comment